Innocent/Corrupt

A narrator is a much stranger toy at the novelist’s disposal than is usually thought. It’s not just something as depressingly ordinary as a character—more a vast system of smuggling. And there’s one kind of narrative voice or tone in particular that offers a way to explore that difficult relationship at the hidden center of every art form: the one between writer and reader (or spectator). Although this tone seems to exist most easily in novels, it isn’t only to be found there—it appears wherever anyone tries to figure out what a monologue might mean, or how to talk to a you. It is garrulous, self-aware, hyper, charming, and occurs internationally, but what makes the voice a form is this: Narrators of the kind I mean are adepts of a confessional mode that’s actually designed to exonerate them completely. What could be more dangerous than someone convinced of his own goodness, his own innocence? Someone who believes that what he feels is far more important than what he actually does.

What I like about this sort of voice is that it takes in both the high aesthetic and the dirty political. And in fact perhaps the only route to the dirty political is through the high aesthetic, and vice versa—or at least that’s what this voice makes you think. I have no idea what name to give this voice I’m talking about. It seems to me an as yet undescribed category. So let’s call it something oxymoronic and impossible. Let’s call it the Innocent/Corrupt.

Swimsuit, “Chandra.” Live at PJ’s Lager House (Detroit, Michigan – June 1, 2012)

From George W. Bush, Decision Points. Chapter “Freedom Agenda,” p. 433:

Putin and I both loved physical fitness. Vladimir worked out hard, swam regularly, and practiced judo. We were both competitive people. On his visit to Camp David, I introduced Putin to our Scottish terrier, Barney. He wasn’t very impressed. On my next trip to Russia, Vladimir asked if I wanted to meet his dog, Koni. Sure, I said. As we walked along the birch-lined grounds of his dacha, a big black Labrador came charging across the lawn. With a twinkle in his eye, Vladimir said, “Bigger, stronger, and faster than Barney.” I later told the story to my friend, Prime Minister Stephen Harper of Canada. “You’re lucky he only showed you his dog.”

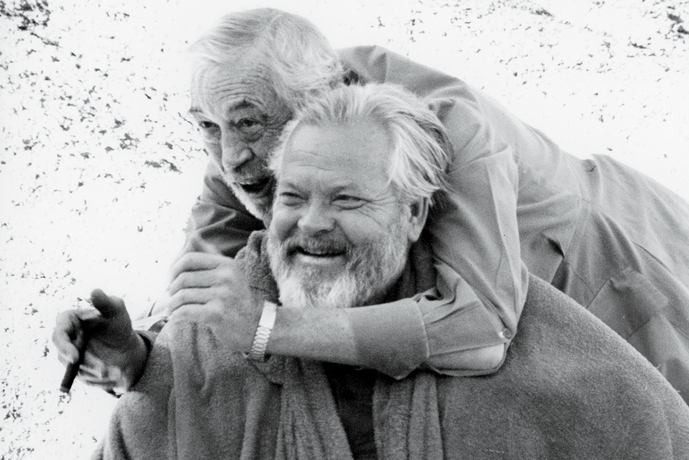

John Huston and Orson Welles, during the filming of the unfinished The Other Side of the Wind. Ph: Mike Ferris.

ROBERT PHILLIPS How many days a week do you work at the library, and for how many hours a day?

PHILIP LARKIN My job as University librarian is a full-time one, five days a week, forty-five weeks a year. When I came to Hull, I had eleven staff; now there are over a hundred of one sort and another. We built one new library in 1960 and another in 1970, so that my first fifteen years were busy. Of course, this was a period of university expansion in England, and Hull grew as much as if not more than the rest. Luckily the vice-chancellor during most of this time was keen on the library, which is why it is called after him. Looking back, I think that if the Brynmor Jones Library is a good library—and I think it is—the credit should go to him and to the library staff. And to the University as a whole, of course. But you wouldn’t be interested in all that.

PHILLIPS What is your daily routine?

LARKIN My life is as simple as I can make it. Work all day, cook, eat, wash up, telephone, hack writing, drink, television in the evenings. I almost never go out. I suppose everyone tries to ignore the passing of time: some people by doing a lot, being in California one year and Japan the next; or there’s my way—making every day and every year exactly the same. Probably neither works.

PHILLIPS You didn’t mention a schedule for writing . . .

LARKIN Yes, I was afraid you’d ask about writing. Anything I say about writing poems is bound to be retrospective, because in fact I’ve written very little since moving into this house, or since High Windows, or since 1974, whichever way you like to put it. But when I did write them, well, it was in the evenings, after work, after washing up (I’m sorry: you would call this “doing the dishes”). It was a routine like any other. And really it worked very well: I don’t think you can write a poem for more than two hours. After that you’re going round in circles, and it’s much better to leave it for twenty-four hours, by which time your subconscious or whatever has solved the block and you’re ready to go on.

The best writing conditions I ever had were in Belfast, when I was working at the University there. Another top-floor flat, by the way. I wrote between eight and ten in the evenings, then went to the University bar till eleven, then played cards or talked with friends till one or two. The first part of the evening had the second part to look forward to, and I could enjoy the second part with a clear conscience because I’d done my two hours. I can’t seem to organize that now.