Search for ‘MATT ’ (136 articles found)

Zizek: 'Good manners in the age of WikiLeaks'

The conspiratorial mode is supplemented by its apparent opposite, the liberal appropriation of WikiLeaks as another chapter in the glorious history of the struggle for the ‘free flow of information’ and the ‘citizens’ right to know’. This view reduces WikiLeaks to a radical case of ‘investigative journalism’. Here, we are only a small step away from the ideology of such Hollywood blockbusters as All the President’s Men and The Pelican Brief, in which a couple of ordinary guys discover a scandal which reaches up to the president, forcing him to step down. Corruption is shown to reach the very top, yet the ideology of such works resides in their upbeat final message: what a great country ours must be, when a couple of ordinary guys like you and me can bring down the president, the mightiest man on Earth!

The ultimate show of power on the part of the ruling ideology is to allow what appears to be powerful criticism. There is no lack of anti-capitalism today. We are overloaded with critiques of the horrors of capitalism: books, in-depth investigative journalism and TV documentaries expose the companies that are ruthlessly polluting our environment, the corrupt bankers who continue to receive fat bonuses while their banks are rescued by public money, the sweatshops in which children work as slaves etc. However, there is a catch: what isn’t questioned in these critiques is the democratic-liberal framing of the fight against these excesses. The (explicit or implied) goal is to democratise capitalism, to extend democratic control to the economy by means of media pressure, parliamentary inquiries, harsher laws, honest police investigations and so on. But the institutional set-up of the (bourgeois) democratic state is never questioned. This remains sacrosanct even to the most radical forms of ‘ethical anti-capitalism’ (the Porto Allegre forum, the Seattle movement etc).

WikiLeaks cannot be seen in the same way. There has been, from the outset, something about its activities that goes way beyond liberal conceptions of the free flow of information. We shouldn’t look for this excess at the level of content. The only surprising thing about the WikiLeaks revelations is that they contain no surprises. Didn’t we learn exactly what we expected to learn? The real disturbance was at the level of appearances: we can no longer pretend we don’t know what everyone knows we know. This is the paradox of public space: even if everyone knows an unpleasant fact, saying it in public changes everything. One of the first measures taken by the new Bolshevik government in 1918 was to make public the entire corpus of tsarist secret diplomacy, all the secret agreements, the secret clauses of public agreements etc. There too the target was the entire functioning of the state apparatuses of power.

What WikiLeaks threatens is the formal functioning of power. The true targets here weren’t the dirty details and the individuals responsible for them; not those in power, in other words, so much as power itself, its structure. We shouldn’t forget that power comprises not only institutions and their rules, but also legitimate (‘normal’) ways of challenging it (an independent press, NGOs etc) – as the Indian academic Saroj Giri put it, WikiLeaks ‘challenged power by challenging the normal channels of challenging power and revealing the truth’.[*] The aim of the WikiLeaks revelations was not just to embarrass those in power but to lead us to mobilise ourselves to bring about a different functioning of power that might reach beyond the limits of representative democracy.

However, it is a mistake to assume that revealing the entirety of what has been secret will liberate us. The premise is wrong. Truth liberates, yes, but not this truth. Of course one cannot trust the facade, the official documents, but neither do we find truth in the gossip shared behind that facade. Appearance, the public face, is never a simple hypocrisy. E.L. Doctorow once remarked that appearances are all we have, so we should treat them with great care. We are often told that privacy is disappearing, that the most intimate secrets are open to public probing. But the reality is the opposite: what is effectively disappearing is public space, with its attendant dignity. Cases abound in our daily lives in which not telling all is the proper thing to do. In Baisers voles, Delphine Seyrig explains to her young lover the difference between politeness and tact: ‘Imagine you inadvertently enter a bathroom where a woman is standing naked under the shower. Politeness requires that you quickly close the door and say, “Pardon, Madame!”, whereas tact would be to quickly close the door and say: “Pardon, Monsieur!”’ It is only in the second case, by pretending not to have seen enough even to make out the sex of the person under the shower, that one displays true tact.

A supreme case of tact in politics is the secret meeting between Alvaro Cunhal, the leader of the Portuguese Communist Party, and Ernesto Melo Antunes, a pro-democracy member of the army grouping responsible for the coup that overthrew the Salazar regime in 1974. The situation was extremely tense: on one side, the Communist Party was ready to start the real socialist revolution, taking over factories and land (arms had already been distributed to the people); on the other, conservatives and liberals were ready to stop the revolution by any means, including the intervention of the army. Antunes and Cunhal made a deal without stating it: there was no agreement between them – on the face of things, they did nothing but disagree – but they left the meeting with an understanding that the Communists would not start a revolution, thereby allowing a ‘normal’ democratic state to come about, and that the anti-socialist military would not outlaw the Communist Party, but accept it as a key element in the democratic process. One could claim that this discreet meeting saved Portugal from civil war. And the participants maintained their discretion even in retrospect. When asked about the meeting (by a journalist friend of mine), Cunhal said that he would confirm it took place only if Antunes didn’t deny it – if Antunes did deny it, then it never took place. Antunes for his part listened silently as my friend told him what Cunhal had said. Thus, by not denying it, he met Cunhal’s condition and implicitly confirmed it. This is how gentlemen of the left act in politics.

So far as one can reconstruct the events today, it appears that the happy outcome of the Cuban Missile Crisis, too, was managed through tact, the polite rituals of pretended ignorance. Kennedy’s stroke of genius was to pretend that a letter had not arrived, a stratagem that worked only because the sender (Khrushchev) went along with it. On 26 October 1962, Khrushchev sent a letter to Kennedy confirming an offer previously made through intermediaries: the Soviet Union would remove its missiles from Cuba if the US issued a pledge not to invade the island. The next day, however, before the US had answered, another, harsher letter arrived from Khrushchev, adding more conditions. At 8.05 p.m. that day, Kennedy’s response to Khrushchev was delivered. He accepted Khrushchev’s 26 October proposal, acting as if the 27 October letter didn’t exist. On 28 October, Kennedy received a third letter from Khrushchev agreeing to the deal. In such moments, when everything is at stake, appearances, politeness, the awareness that one is ‘playing a game’, matter more than ever.

However, this is only one – misleading – side of the story. There are moments – moments of crisis for the hegemonic discourse – when one should take the risk of provoking the disintegration of appearances. Such a moment was described by the young Marx in 1843. In ‘Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Law’, he diagnosed the decay of the German ancien regime in the 1830s and 1840s as a farcical� repetition of the tragic fall of the French ancien regime

. The French regime was tragic ‘as long as it believed and had to believe in its own justification’. The German regime ‘only imagines that it believes in itself and demands that the world imagine the same thing. If it believed in its own essence, would it … seek refuge in hypocrisy and sophism? The modern ancien regime is rather only the comedian of a world order whose true heroes are dead.’ In such a situation, shame is a weapon: ‘The actual pressure must be made more pressing by adding to it consciousness of pressure, the shame must be made more shameful by publicising it.’

This is precisely our situation today: we face the shameless cynicism of a global order whose agents only imagine that they believe in their ideas of democracy, human rights and so on. Through actions like the WikiLeaks disclosures, the shame – our shame for tolerating such power over us – is made more shameful by being publicised.

Obsession with compression

Compression is a process that aims for greater efficiency. Compression streamlines all that is ‘unnecessary’ by compacting a product to reveal only its most essential components. The compressed product’s new, slender form allows it to be used, seen, transmitted or reproduced with greater ease than its previously bulky or complicated body. An argument can be made that whatever is able to be used with the greatest ease is that which has been compressed to the fullest extent. The internet has compressed many things already previously compressed, creating objects both extremely heavy in connotations and extremely light at first appearance. Just as spoken language is a compression of lived experience, so too is the written word a compression of spoken language, and so too is net-speak an even further compression of all of these things. A smiley face emoticon is seen as a frivolous token of online chatter- unless you consider it the latest technologically-bound stop in the progression of humanity’s desire to articulate joy, then it becomes something a bit more complex.

Ideally, compression does not delete information or material but conceals it within itself, making all hidden components readily accessible should the person interacting with a compressed product wish to unzip or re-expand its contents. Of course not all methods of compression lend themselves to different subjects equally well. Compressing a cat’s personal space for plane travel in the manner a watermelon is compressed for a fruit smoothie would be disastrous. As art is digitally mediated, so too does it become materially and experientially compressed. This inevitably creates a dichotomy of quality of experience versus ease of access. Positions over which or if any forms of compression should be applicable to art arise. People against art’s digital mediation claim it to be a vulgar distortion of experiential affect and a forcible removal of aesthetics. People in support of art’s digital mediation point to the way it opens previously rigid institutional and architectural boundaries of participation, allowing an exponentially larger number of viewers to become aware of and join in art’s discourse. Though in the past I have favored the latter of these two positions, I wonder if such distinctions are quite so black and white. For instance, what role do formats that are native to digital viewing play in this conversation? They cannot be judged against the backdrop of a formerly physical existence but must be critically analyzed unto themselves. One such example that comes to mind is the artistic GIF.

The general popularity of GIFs is easy to understand. They’re simple to make, playfully animated, cross-browser compatible and fun to watch. GIFs have a history in both vernacular net use and internet art, as well as a history at the intersection between the two. As a visual medium, GIFs are caught in a space sandwiched between still images and film. Arguably, all film is just a rapid procession of still images, but while film conceals this fact the GIF often reveals which frames comprise it by plodding through them in a manner similar to stop animation during the process of loading. GIFs lend themselves to subject matters that may be quickly summed up in the fewest number of frames possible or to content that has no beginning or end and may be understood equally well starting from any moment in a brief, looping format. As writer Jonah Weiner says

[Many GIFs] are built around the payoff moments of Did you see that? style viral videos. These GIFs are structured like jokes, with the barest minimum of set-up … They get to the point instantaneously, and at the exact moment when one feels the impulse to rewind and watch the climax again, the loop restarts right where it should … Like an enhanced bumper sticker or T-shirt, the GIF offers a pithy, punchy means for self-expression.

This kind of self-expression is largely conversational; on message boards the GIF provides an excellent way of responding to a previous poster in a direct manner that transcends the time necessary to read and decode language. The lure of using a GIF is that it is designed not to be poured over as an individual object of dense decoding but to be seen, to trigger an immediate response, and be moved on from. On the subject of the GIF’s accepted immediacy, writer Joshua Kopstein states

Human memory is intimately tied to isolated moments in time. According to the Atkinson-Shifrin model — the same one that divided human memory into long-term, short-term and sensory — most of the things we experience are not committed to long-term memory beyond a few select moments. So it makes sense that we’ve embraced GIFs as these suspended moments in time, looping only the information necessary to conjure a particular emotion or memory.

The GIF’s straightforward looping mechanism revels in its own simplicity and the manner in which it professes to be nothing more profound than what 3~ seconds of your time can possibly allow for as a work of visual art. In an online environment that exalts immediacy and ease of use, the GIF is not a fetishization of the past or Web 1.0 culture- as many have argued- but a fetishization of the internet’s propensity for compressing information to the furthest degree possible. In a world of Macbook Airs, external hard drives the size of a thumb, and 140 character limits on textual communication, the GIF is a suitable alternative for those who can’t quite make it through a 2 minute Youtube video without advancing forward to the 1:00 and 1:30 minute markers after the first 10 seconds prove too dull for viewing. The most crucial question for artists to ask in response to the GIF’s obsession with compression is whether the GIF is a true harbinger of conceptual efficiency or an ornamental novelty of its own lightness?

GIFs do not require an embedded player to be viewed and have remained functional throughout many shifts in applicable file formats on the web. This longevity and uniform accessibility has lead many to characterize the GIF as a file format as democratic as the internet purportedly aspires to be. However, unlike Hito Steryl’s accurately egalitarian description of the poor image, the low visual quality of a GIF is not a result of pirated mass reproduction or individuals cycling images through a slew of diverse copying and transfer methods. Instead, the GIF’s limited capacity for narrative and often pixilated appearance is due to the increased bulk each frame adds to its total file size, subsequently slowing down the process of loading and viewing the larger the file gets. Without the external support of a video player, the GIF must behave as an image while appearing to be a video.

As a culturally distinct and informationally narrowed format, the content of an artistic GIF rarely strays far from the realm of the expected due to the inherently minimal range of visuals and narrative advancements it may include as a time-based medium. All forms of compression eventually meet their logical end, where whatever material that was compressed is no longer able to be recovered in quite the same manner it previously existed, resulting in an unzipped product that appears to be a faint shadow of the dense form it once took. The fault of the artistic GIF is not that it has rendered conceptually rich subjects to a point incapable of being critically expanded upon with conceptual depth, but that the format itself is a censorship of an amount of information necessary to create ideologically rich narratives transcendent of their own interface. In a recent essay on the state of internet-inform

ed art, curator Lauren Cornell states

While the field of art online continues to thrive, art engaged with the internet does not need to exist there; because the internet is not just a medium, but also a territory populated and fought over by individuals, corporations, and governments; a communications tool; and a cultural catalyst.

The idea that art’s subject matter need not address the same medium it assumes is an adequate description of a contemporary field of art making that has increasingly come to rely less on medium specificity for critical validation. As Cornell echoes, the best art on the internet or otherwise exceeds its own medium, inspiring realizations divorced from whatever it is being transmitting through. The GIF is indelibly and formally linked to the compressed boundaries of the file format that transmits it, allowing art viewers none of the suspension of disbelief necessary to think the GIF they are looking at is not, in fact, a GIF at any moment of their viewing. The solution to the artistic GIF’s status as a pre-emptively self-referential medium would require it to betray its own maxim of economical viewing and transfer. Impossibly, this would force the GIF to aesthetically become, in a word, inefficient. Some problems just can’t be fixed. The artistic GIF will have to deal with it.

Elizabeth Bishop and The New Yorker

One of the pleasures of “Elizabeth Bishop and The New Yorker,” a new collection of her correspondence with that magazine’s poetry editors, is snooping around in the excellent footnotes and front matter for the wicked comments she made behind the magazine’s back. She deplored its “ ‘How nice to be nice!’ atmosphere,” its sense of “false refinement,” and declared that reading the magazine was “getting to be like reading a quilt — eating a quilt, I mean — full of starchy fillers and ‘enough water to properly prepare’ etc.”

After The New Yorker bought one of her rare short stories, Bishop wrote to a friend: “At first I thought it was my best, but after they took it naturally I had serious doubts.” When the magazine rejected one of her poems, which had some slight political content, she suggested that the editors feared “to annoy their Republican readers.”

Garry Kasparov on Bobby Fischer

Young, famous, rich, and on top of the world, Fischer first took some time off. Then a little more, then more. Big tournaments were relatively rare back then, and it didn’t shock anyone that Fischer didn’t play in the first year after winning the title. But a second year? The three-year world championship cycle, run by the World Chess Federation (FIDE), was already grinding along to produce the man who would be Fischer’s challenger in 1975. Obviously he could not wait until then to play his first chess game since defeating Spassky.

Yet that is exactly what he did. Long before the three years were up, however, the arguments about the format of the 1975 world championship match were underway. Fischer, surprising no one, had many strong ideas about how the event should be run, including returning to the old system with no limit to the number of games. As he does with many of the chess world’s eternal debates around Fischer, Brady makes this long story mercifully short, letting the reader decide whether or not Fischer’s demands were extreme but fair or blatantly self-serving. FIDE would not give in to everything and for Fischer it was all or nothing. In the end, the American resigned the title.

This stunning news launched one of the greatest known bouts of psychoanalysis in absentia the world has ever seen. Why didn’t Bobby play? Did he believe so strongly that his system for the championship was the only right one that he was willing to give up the title? Had it all been a bluff, a ploy to gain an advantage or more money? Did even he know for sure?

One theory that was not often heard was that Fischer might have been more than a little nervous about his challenger, the twenty-three-year-old leader of the new generation, Anatoly Karpov. In fact, when I proposed this possibility in my 2004 book on Fischer, My Great Predecessors Part IV, the hostile response was overwhelming. These were not merely the protestations of Fischer fans saying I was maligning their hero. There is a great deal of evidence to build Fischer’s case as the overwhelming favorite had the match taken place. This includes testimony by Karpov himself, who said Fischer was the favorite and later put his own chances of victory at 40 percent.

Nor am I arguing that Karpov would have been the favorite, or that he was a better player than Fischer in 1975. But I do think there is a strong circumstantial case for Fischer having good reasons not to like what he saw in his challenger. Remember that Fischer had not played a serious game of chess in three years. This explains why he insisted on a match of unlimited length, played until one player reached ten wins. With draws being so prevalent at the top level, such a match would likely have lasted many months, giving Fischer time to shake off the rust and get a feel for Karpov, whom he had never faced.

Karpov was the leading product of the new generation Fischer had created. They had a different approach than all the leading players Fischer had defeated on his march to the title and he had very little experience facing this new breed. In the candidates matches Karpov had crushed Spassky and then defeated another bastion of the older generation, Viktor Korchnoi. I can imagine Fischer going over the games from those matches, especially Karpov’s meticulous play and steady hand against Spassky, and beginning to feel some doubt.

Frank Brady discards this possibility hastily, perhaps justly so since there is no way we will ever know what was in Fischer’s head or, most unfortunately, what would have happened had the Fischer-Karpov match taken place. But I was surprised to read that there were contemporaries who put the blame for the match not taking place squarely on Fischer’s fears. Brady quotes New York Times chess columnist Robert Byrne, who wrote a piece titled “Bobby Fischer’s Fear of Failing” just a few days after Karpov was awarded the title. Byrne did not mention Karpov as a threat—he says he wouldn’t have stood a chance—but he pointed out that Fischer had always taken great precautions against defeat, to the point of declining to play in other events as well when he felt too much was being left to chance.

Brady’s dismissal of this theory misses the point: “What everyone seemed to overlook was that at the board Bobby feared no one.” Yes, once at the board he was fine! Where Fischer had his greatest crisis of confidence was always before getting to the board, before getting on the plane. Fischer’s perfectionism, his absolute belief that he could not fail, did not allow him to put that perfection at risk. And in Karpov, I have no doubt, especially after a three-year layoff, Fischer saw a significant risk.

One of the countless, and endless, debates around Fischer was whether his behavioral excesses were the product of an unbalanced, yet sincere, soul, or an extension of his all-consuming drive to conquer. Fischer had his strong principles, but the predator in him was well aware of the effect his antics had on his opponents. In 1972, the gentlemanly Boris Spassky was unprepared to deal with Fischer’s endless postponements and protests and played well below his normal level in Reykjavik.

Karpov, meanwhile, had beaten Spassky convincingly in 1974 without any gamesmanship. There is a fair case to be made that the match with Spassky was one of Karpov’s greatest-ever efforts and Fischer would not have failed to sense his challenger’s quality. The shades of color in real life often baffled Fischer, but he always saw very clearly in black and white. Along with Karpov’s modern play, Fischer would have seen a hard young man who had none of the older generation’s romantic notions and who would not be unsettled by off-the-board sideshows. (All reports say that Fischer was scrupulously correct at the board.) No matter how sincere Fischer may have been about his protests—playing conditions, opponent’s manners, and always money—they were as much a part of his repertoire as the Sicilian Defense.

The debacle of Fischer’s resignation led to yet another unanswerable question. Would Fischer have played had FIDE given in to all his demands? FIDE had accepted all of his conditions but one, that should the match reach a 9-9 tie Fischer would retain the title. This meant the challenger had to win by at least a 10-8 score, a substantial advantage for the incumbent. Had FIDE agreed and had Fischer come up with yet more demands, the book could have been closed in good conscience. Instead we missed out on what would have been one of the greatest matches in history and must wonder for eternity what Fischer would have done. In that light, 10-8 hardly seems like such a disadvantage.

Ironically, after Fischer was off the scene FIDE implemented some of his suggestions, including the unlimited match. Karpov also received the protection of a rematch clause, which gave him at least as big an advantage as Fischer had demanded. The absurdity of an unlimited match was only conclusively proven when Karpov and I dueled for a record forty-eight games over 152 days before the match was abandoned without a winner. And we were playing only for six wins, not Fischer’s desired ten.

Brady gives a straightforward account of Fischer’s rise to stardom as the youngest US champion ever, at fourteen in 1957, who then moved onto the world stage. It defied belief that a lone American could beat the best that the Soviet chess machine could produce. But even Walt Disney would hesitate to conceive of the story of a poor single mother trying to finish her education while moving her family from place to place and her unfocused young son from scho

ol to school—all while being investigated by the FBI as a potential Communist agent.

T.S. Eliot: The critic as radical

Eliot was too subtle not to recognize (and too honest not to acknowledge) that his more general pronouncements about political philosophy were unsatisfactory. Like all general pronouncements (in my William James-ian view, at least), they reduce to truisms. Continuity is best, except where change is necessary. Much tradition, some innovation. Firm principles, flexibly adapted. His often-cited remark (in praise of Aristotle) that “the only method is to be very intelligent” helps in estimating his own political criticism.

Concerning two matters of large contemporary relevance, Eliot was profoundly, though unsystematically, intelligent. Eliot’s political utterances were, for the most part, fragmentary and occasional: occurring in essays, lectures, and the regular “Commentaries” in his great quarterly The Criterion. His compliment to Henry James—“he had a mind so fine no idea could violate it”—applied to Eliot as well, for better and worse. He was never doctrinaire; but on the other hand, he was rarely definite. As one commentator observes: “To gesture toward, but not to reveal; to pursue, but not to unravel, this is Eliot’s procedure.” But although he eschewed programs, there is much matter in his asides.

About economics, he repeatedly professed theoretical incomprehension. But just as often, he professed skepticism that any immutable laws of political economy proved that extremes of wealth and poverty were inevitable or that state action to counter disadvantage must be futile. Disarmingly, he acknowledged:

I am confirmed in my suspicion that conventional economic practice is all wrong, but I can never understand enough to form any opinion as to whether the particular prescription or nostrum proffered is right. I cannot but believe that there are a few simple ideas at bottom, upon which I and the rest of the unlearned are competent to decide according to our several complexions; but I cannot for the life of me ever get to the bottom.

Nevertheless, “about certain very serious facts no one can dissent.” For “the present system does not work properly, and more and more are inclined to believe both that it never did and that it never will.”

What were some of these “very serious facts”?

… the hypertrophy of Profit into a social ideal, the distinction between the use of natural resources and their exploitation, the advantages unfairly accruing to the trader in contrast to the primary producer, the misdirection of the financial machine, the iniquity of usury, and other features of a commercialized society.

Sometimes he wondered whether Western society was “assembled round anything more permanent than a congeries of banks, insurance companies and industries, and had any beliefs more essential than a belief in compound interest and the maintenance of dividends.” On one occasion he sounded almost like a communist:

Certainly there is a sense in which Britain and America are more democratic than [Nazi] Germany; but on the other hand, defenders of the totalitarian system can make out a plausible case for maintaining that what we have is not democracy but financial oligarchy.

Indeed, Eliot was full of surprises on the subject of communism. Try to imagine his drearily predictable acolytes at The New Criterion saying something like this:

I have … much sympathy with communists of the type with which I am here concerned [i.e. “those young people who would like to grow up and believe in something”]. I would even say that … there are only a small number of people living who have achieved the right not to be communists.

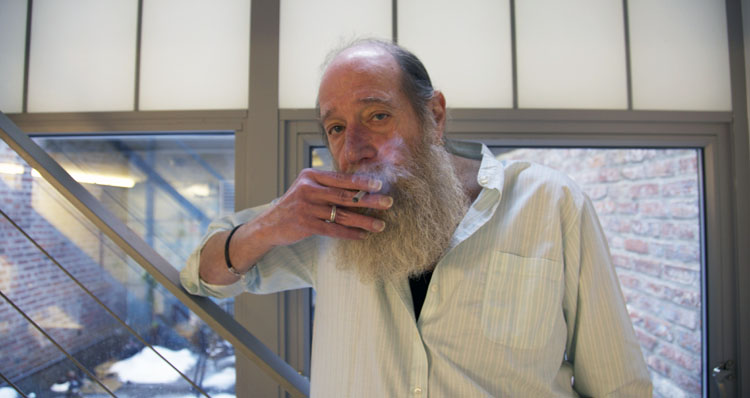

Studio Visit: Lawrence Weiner

The artist Lawrence Weiner lives on a quiet street in the West Village, in what was once an old laundromat built in 1910 and is now an unobtrusive five-level town house designed by the firm Lot-ek. You may recognize some of the architecture: Lot-ek is often cited for it inventive reuse of prefabricated objects (like shipping containers) and other industrial materials. In fact, the penthouse floor of Weiner’s home is build from discarded truck bodies. The floor below is the bedroom, the floor below that houses Weiner’s archives, and the first floor is the kitchen and dining room. At the basement level, Weiner keeps his studio, where he works. Not long ago, I stopped by to take photographs of his home and talk.

I didn’t come from a background that had any idea about what contemporary art was, it was not anti or pro, it had nothing to do with it. I do remember something my mother said when I was sixteen. I was going off to college, and I said, “I think I’m going to be an artist, not a professor of philosophy.” They all assumed I would be a professor because I’m good at logic, and she looked at me and she said, “Lawrence, you’ll break your heart.” And I said, “Why?” And she said, “Art is for rich people and women.”

I was more into labor organizing and civil rights in the fifties and the sixties. Through a lot of happenstance, I discovered this thing called art—what we call contemporary art. Where you try to do that funny thing where you don’t want to fuck up somebody’s day on their way to work, you want to fuck up their whole life. Art is a possibility to present logic structures that can change people’s perception of their entire existence. I gave it a shot, and I guess I just kept doing it.

Weiner’s work often uses typographic texts. ‘We don’t use any computers in the beginning,’ he told me. ‘It all starts here.’

We’ve lived here since some time in the eighties. I guess that’s a long time ago. I have no idea. I started showing when I was eighteen. I had my first show in 1960, and I don’t know what’s old and what isn’t old.

I lived on Bleecker Street for thirty some odd years, and then, because it was rental, we were going to lose it. It was falling apart anyhow, and it was one room and small. I had to find another place. I always liked the West Village; I grew up in the South Bronx, I went to high school down on Fiftieth Street, at Stuyvesant, and I was always taken up by the group of people that used to live in this area—Kerouac and that whole scene. We found this little house, and lived in it for like twenty years, and then the lords of the earth were building every place around us and the light wasn’t right anymore, and we woke up one morning and decided that artists are not victims. Just like that. It’s a landmarked area, and it’s completely locked down, but we collapsed the house and built a brand new one.

I like the neighborhood, still. Nothing to do with the fact that there are seventeen-million-dollar houses. There are rent-controlled apartments left. The neighborhood, for all it’s faults, is still is one of the last totally mixed neighborhoods that functions as a neighborhood. And it accommodates the enormous quantities of those sad people from the suburbs who come in every day to go to the same two Marc Jacobs and Ralph Lauren shops. But it's still a place when you walk out in the morning in your bathrobe, and buy a pack of cigarettes if you need to. Somebody will stare at you from the suburbs, but they’re so harassed from having to park their car that you don’t really care. And the people who are angry about paparazzi are people who wish they were having their picture taken. It’s some poor guy standing out in the rain to take a picture of somebody getting their mail out of the mailbox. That’s pretty kinky.

I don’t do lunch. I don’t like lunch, I don’t understand it. It seems to completely break your day, and things I do seem to take weeks, and if you start working on something, you want to continue to work. So I sort of work and I work and the other people go out to lunch and they do things, and I just work my way through. It’s not very exciting. And people who come by, like you, and they come by and they have a cup of coffee, and they sit and they chat. I’m a real cocktail party kind of person. I prefer cocktail parties to anything else. With a cocktail party people can talk, and they’re not trapped.

There’s nothing sillier than an MFA. What does it mean? Did you learn anything? No. To be a master you have to learn languages and you have to have these things. Nobody gets them. I don’t think the art form is that complicated that you need a college course in order to read it. I really don’t. Art and fashion are the last to bastions where the product itself is what attracts attention, it really doesn’t much matter who made it. There’s this legitimization of something with an MFA. But Gaultier draws a shoe, they look at it, they put the shoe in production, it comes out, and it works. Nobody had to know anything about the person. Art is the same thing, something is built and shown, and it enters the culture. I like schools, I like people to go to school, but the purpose of the Academy is to give answers. If they don’t have an answer, they give a solution. The purpose of art is to ask questions. They’re antithetical.

I wouldn’t tell a young person what to do. They’d have to figure out their aspirations, why they are making art, and they’d have to surprise me. How do you relate to people what it was like in the late sixties and the seventies, that there was a brutal war going on that did affect everybody, not just soldiers, in the United States? There was a whole different ball game going on. How do you tell somebody what they’re supposed to do? And how do I know why somebody else is making art? Sorry, I don’t have a pronouncement. I wish I did. Wisdom does not come with age. Skills come with age, but wisd

om, I doubt it very, very much.

Letters on the raging peloton

Iain Sinclair’s article on cycling in London reminded me of my short time working as a courier in the mid-1990s (LRB, 20 January). The semi-crazed feelings of megalomania that scything through the streets and pathways of the City of London gave me were intoxicating and frightening (and thankfully short-lived). The sense of invincibility and power was tempered by the guilt that roamed my thoughts in the evenings, after the adrenalin subsided and the dirt and sweat – sometimes blood – were washed away. Even today, when I see such freewheeling behaviour, I occasionally feel somewhat shamefaced at the memories. Frightened pedestrians, astonished motorists and dented cars were the collateral damage of work that relied on speed and aggression for its meaning, satisfaction and productivity: the quicker the jobs were completed, the more jobs done, the more money made. Your equipment mattered too. My Brick Lane-bought Raleigh road bike was woefully inadequate, but was soon painted (first kingfisher blue, then Marin fluorescent yellow) and modified. Derailleur gears were quickly removed and clothes and bag were adapted. I learned my lessons: about London, its geography, streets and how it fits together. Based at Slaughter and May’s car park near Moorgate, small gangs of us – novices, masters and legends – would smoke and eat and fidget with radios, keen to be on our way. Conversation was never very expansive. Stories of accidents and death were common. Some of the career couriers were cycling obsessives, had all the gear, and worked because it paid for their training. For others, like me, it was simply casual work, if somewhat in your face.

Simon Down

Newcastle-upon-Tyne

Wasn’t it Jarry, mentioned by Iain Sinclair, who used a revolver instead of a bicycle bell? And didn’t he reassure a pregnant woman who complained that he had so startled her that she might lose her baby: ‘In that eventuality, madame, I shall make you another’?

David Maclagan

Holmfirth, West Yorkshire

At the risk of being anorakesque I’d like to point out that Dr Alex Moulton did not invent any outer ring to protect the rider from chain ring teeth, and while a clip-on plastic ring appeared on F-frame Moultons, there is no such thing on later space frame machines (Letters, 3 February). Guarding against the chain goes back into early cycling history, the full chain case appearing on Raleigh, Humber, Rudge etc any time from 1900, and on Dutch bikes still today, although nowadays plastic. Top of the range Sunbeam, made famous by Elgar, had its patent Small Oil Bath. Riding my Sunbeam wearing plus-fours (correct period costume), I don’t need to worry about the social implications of trouser clips. Later chain guards became the ‘hockey stick’, light steel bearing decals of the builder’s name in Britain, often aluminium pressed with the maker’s name in Europe. As for ladies’ protection, the skirt guard needed many small holes round the top of the rear mudguard and a web of string down to the chain stay to keep the skirt out of the spokes of the rear wheel.

Some are of the opinion that the trouser clip is very middle class, any working man cycling to work just sticking his turn-ups into his socks, or if wearing overalls being unworried by oil. Should a Marxist academic renounce that bourgeois badge of shame the trouser clip by sticking his trousers into his socks?

Stephen Kay

Abergavenny, Monmouthshire

I recall the 1950s, when a group of cycle-clip unchallenged teenage friends would meet at Liverpool Pier Head on Sunday morning, cross on the ferry to Wallasey and cycle 30-odd miles on the New Chester Road (suicidal today) into the Clwyd Hills of North Wales, pack-lunch and back again; a prospect far less daunting than Iain Sinclair’s experience battling the Peletonistics of Boris’s Barclays branded bike battles on the towpaths of North London, where I imagine neither Moulton small-wheelers nor unbranded loose T-shirts are much in evidence (Letters, 3 February).

Gordon Petherbridge

Buckingham

Parts of Chopin

Cast of Chopin’s left hand by Clesinger

Many people who had not been present at Chopin’s death would later claim to have been there. “Being present at Chopin’s death,” writes Tad Szulc, “seemed to grant one historical and social cachet.”[56] Those actually around his bed appear to have included his sister Ludwika J�drzejewicz, Princess Marcelina Czartoryska, Solange and Auguste Clesinger (George Sand’s daughter and son-in-law), Chopin’s friend and former pupil Adolf Gutmann, his friend Thomas Albrecht, and his confidant, Polish Catholic priest Father Aleksander Je�owicki.[52]

Later that morning, Clesinger made Chopin’s death mask and a cast of his left hand, to which Chopin had given prominence in his compositions. Before the funeral, pursuant to his dying wish, his heart was removed. It was preserved in alcohol (perhaps brandy) to be returned to his homeland, as he had requested.[53] His sister smuggled it in an urn to Warsaw, where it was later sealed within a pillar of the Holy Cross Church on Krakowskie Przedmie�cie, beneath an epitaph sculpted by Leonard Marconi, bearing an inscription from Matthew VI:21: “For where your treasure is, there will your heart be also.” Chopin’s heart has reposed there – except for a period during World War II, when it was removed for safekeeping – within the church that was rebuilt after its virtual destruction during the 1944 Warsaw Uprising. The church stands only a short distance from Chopin’s last Polish residence, the Krasi�ski Palace at Krakowskie Przedmie�cie 5.

Frank Kermode on William Empson

In 1941 [William] Empson met Hetta Crouse, an Afrikaans-speaking South African artist who was working in the African Service, and they married at the end of the year. Two sons were born within the next three years – nothing unusual there, but for other reasons this marriage might well have been thought peculiar. Haffenden does full justice to the extraordinary Hetta, tall, beautiful, funny, a hard drinker, and no more than her husband a lover of domestic peace, cleanliness and conventional morality. The marriage was ‘open’ and Hetta set the pace by having lots of lovers. The poet encouraged her in this, believing in the virtues of the ‘Consenting Triangle’. In a long and curious poem called ‘The Wife Is Praised’, here printed for the first time, he explains this preference:

Did I love you as mine for possessing?

Absurd as it seems, I forget;

For the vision of love that was pressing

And time has not falsified yet

Was always a love with three corners

I loved you in bed with young men,

Your arousers and foils and adorers

Who would yield to me then.

And so on, for 25 stanzas, unambiguous about the preferences of the parties, but also firm that the marriage was far from lacking in love. There were times when Hetta’s exercise of her freedom may have caused Empson some pain; he missed her badly when she went off to Hong Kong for a year with a lover, and seems to have been a little unhappy when she added illegitimately to the family (possibly, as Haffenden suggests, more because of his sense of obligation to his brother as head of the family than to common or garden jealousy). And it may have hurt that while he worked at Sheffield University, as he did for 18 years, living in conditions of squalor that amazed all who saw them, Hetta rarely paid him a visit. Not that conditions in their Hampstead house were very different from those of the Sheffield ‘burrow’ – they were described by Robert Lowell as having ‘a weird, sordid nobility’ – but of course it was much larger, and the company tended to be noisy and numerous, whereas in Sheffield he depended on his middle-class academic colleagues for talk and drinking company and even for baths, and nursing when he was unwell. More comfort was provided by Alice Stewart, a distinguished Oxford doctor and almost a Nobel Prize winner, with whom he had a long, intermittent and affectionate affair.

The Consenting Triangle was not a passing fancy but a serious preoccupation. An important aspect of Empson’s character was his bulldog unwillingness to give up an idea, and he was always ingenious in discovering in favoured works of literature evidence in support of his own theories, literary, social or psychological. For him sexual freedom was an ethical imperative even if the consequences might sometimes be painful. His belief that artists and people of intellect must break with social convention in order to bring about beneficial change naturally applied to sex as well as everything else.

These leading ideas would spread and colour his thinking about matters that might have been thought independent of them. One such instance is his view of the story Joyce tells in Ulysses. It was in 1948 that he first outlined the theory in a letter to his wife: Bloom would like to make love to Molly but hasn’t done so for ten years, since his first son died, though he is keen to have another child. If he could get Molly away from Boylan and ‘get her to bed with Stephen’ he thinks he could manage it provided Stephen preceded him – perhaps when Stephen returned to Eccles Street, as he promised. Joyce was apparently ‘shy’ about this bit of narrative, and hid the point from his readers. Not from Empson, however, who expounded it several times adding more and more detail in evidence: for example, in two successive issues of this journal in August and September 1982, and finally in the posthumous collection Using Biography. He reached a point where he could not believe an unprejudiced reader could help finding what Joyce had rather cravenly hidden; and in any case he would presumably have given up the hope of a triangular arrangement by the time he started Finnegans Wake. But we are to understand that his desire for it had been urgent, and Empson studies it with appropriate intensity: the triangular outcome is ‘amply foretold’.

On 'Modern Family'

From a New York Times piece about Modern Family:

Is there something in the culture today that craves this direct emotion? “A natural tendency of situation comedies is to shy away from emotion,” said Jesse Tyler Ferguson, who plays Mitchell. “There’s been an absence of well-grounded, family comedy on television. Instead we’ve had fantastic snarky comedies, like ‘Seinfeld’ and ‘Arrested Development.’ I think people miss shows like ‘The Cosby Show’ and ‘Family Ties’ that showed true family values.”

But not all earlier shows insisted on sweetness and light. The defining shows of the 1970s — Norman Lear’s “All in the Family,” “Maude” and “The Jeffersons” — tackled grittier fare, from infidelity to racism. “Modern Family” is a smart show — Phil quotes evolutionary psychology, Cam and Mitchell have primitive art on the walls. One episode mined the notion that it takes 10,000 hours to master a skill, made popular in Malcolm Gladwell’s “Outliers.”

But it’s also timid. In today’s global village, a gay kiss is considered controversial and breaking up with your boyfriend by texting is cutting edge. Edith Bunker, on a show that drew twice as many viewers, was the victim of an attempted rape. Maude had an abortion. Archie Bunker kissed a transvestite.

Direct emotion may be considered bold because TV once adhered so slavishly to the ironic kitsch of Seinfeld and The Simpsons, but as Adorno observed, it’s also a value loaded with reactionary history, and today’s buffet of primetime shows is a case-in-point. I have become convinced that we’re living in a TV era not unlike the late 80s. In that time, of course, HBO was shocking people with overtly political fare like Tanner ’88, while mainstream television avoided controversy utterly because (as I have speculated elsewhere) the demographic bump driving Nielsen metrics were late thirties, approaching middle age, and quite simply getting nostalgic.

Today, we have a similar selection. Anodyne comedies like Modern Family and Parks and Recreation present a pleasant, untroubled picture of the present at the same time that nostalgic shows like Glory Dayz (spiritual predecessor: The Wonder Years) present a romanticized past. Glee allows parents to project desired attributes onto their school-age kids. The Office, now far from Ricky Gervais’ unsparing portrayal of the corporate workplace, presents us a picture of American work that is fundamentally benevolent: the crazy bosses are quirky (and backwardly effective!) and careerists like Dwight Schrute are moved to the margins; everywhere, TV tells us, the common sense of the American mainstream prevails.

The late 80s feast of saccharine ended because advertisers became aware (through MTV) of another, younger demographic with their own ideas. If such a demographic existed today, where would they find them?

[Postscript: The obvious answer is that the internet now fills that role. There are cases for and against. For one thing, the internet is a different animal; many things that perfectly suit online behavior (comedy Twitter accounts, casual games) lend themselves poorly to TV formats. Some things, like YouTube Poop and SomethingAwful memes, have a doggedly insular appeal that would be wounded by any compromise.

On the other hand, MTV aired some pretty bizarre shit back in the day. It may be a matter of having TV stations staffed entirely by young people. Young people confuse advertisers, occasionally, into a benign neglect under which programming flourishes. But judging by the past, it can only be a matter of time before the same generation ages, turns against the lack of standards, and becomes incapable of producing or airing innovative shows. What’s to be done? Any idiot can make a movie now, with enough time and low enough standards. Same with a record, same with a book. Those are all engaged media. TV is one of the last remaining fortresses of the gatekeepers, and that sits uneasily beside the spirit of the internet.]