Ricki, don't lose that number

From a letter written by Patrick Leigh Fermor to Enrica Soma in 1961. Soma was a model and ballerina, and the wife of the director John Huston. Fermor was the author of numerous travel books and memoirs. The letter is included in Patrick Leigh Fermor: A Life in Letters, which was edited by Adam Sisman. It will be published in November by New York Review Books.

My darling Ricki,

1,000 thanks for your Paris letter, and apologies for delay. I’ve committed myself, only yesterday too, to devoting myself to my mama in the country this weekend, and I’m such a neglectful and intermittent son that I can’t put it off now. I am longing to see you and hate the thought of your vanishing out of reach for what seems such an age, all unembraced!

I say, what gloomy tidings about the CRABS! Could it be me? I’ll tell you why this odd doubt exists: Just after arriving back in London from Athens, I was suddenly alerted by what felt like the beginnings of troop movements in the fork, but on scrutiny, expecting an aerial view of general mobilization, there was nothing to be seen, not even a scout, a spy, or a dispatch rider. Puzzled, I watched and waited and soon even the preliminary tramplings died away, so I assumed, as the happy summer days of peace followed one another, that the incident, or the delusive shudder through the chancelleries, was over. While this faint scare was on, knowing that, thanks to lunar tyranny, it couldn’t be from you, I assumed (and please spare my blushes here!) that the handover bid must have occurred by dint of a meeting with an old pal in Paris, which, I’m sorry to announce, ended in brief carnal knowledge, more for auld lang syne than any more pressing reason. On getting your letter, I made a dash for privacy and thrashed through the undergrowth, but found everything almost eerily calm: fragrant and silent glades that might never have known the invader’s tread. The whole thing makes me scratch my head, if I may so put it. But I bet your trouble does come from me, because the crabs of the world seem to fly to me, like the children of Israel to Abraham’s bosom, a sort of ambulant Canaan. I’ve been a real martyr to them. What must have happened is this. A tiny, picked, cunning, and well-camouflaged commando must have landed while I was in Paris and then lain up, seeing me merely as a stepping-stone or a springboard to better things, and, when you came within striking distance, knowing the highest when they saw it, they struck (as who wouldn’t?) and then deployed in force, leaving their first beachhead empty. Or so I think! (Security will be tightened up. They may have left an agent with a radio who is playing a waiting game . . . )

I wonder whether I have reconstructed the facts all right. I do hope so; I couldn’t bear it to be anyone but me. But at the same time, if it is me, v. v. many apologies. There’s some wonderful Italian powder you can get in France called Mom — another indication of a matriarchal society — which is worth its weight in gold dust. It is rather sad to think that their revels now are ended, that the happy woods (where I would fain be, wandering in pensive mood) where they held high holiday will soon be a silent grove. Where are all their quips and quiddities? The pattering of tiny feet will be stilled. Bare, ruin’d choirs . . . Don’t tell anyone about this private fauna. Mom’s the word, gentle reader.

Jonathan Raban to grandmother's house

…When my mother had enough petrol coupons, we’d drive to Granny’s house in Sheringham, a long ride of nearly twenty miles. The narrow, twisting road ran past Little Snoring and on to Holt, where we often stopped to break the journey and look in shop windows. Then, from a wooded ridge, the land below us was rimmed with the mysterious sea. Here my mother switched the engine off and let AUP 595 coast downhill. For a mile or more, there was just the sound of the wind, the rustle of tyres on gravel, the creaking of the chassis, as the car submitted to the gravitational pull of Granny’s house. My mother had enlisted as an ambulance driver early in the war and never missed an opportunity to save petrol. She allowed the car to come almost to a standstill before switching the ignition back on and letting out the clutch, so that it restarted with a series of bone-shaking jerks and a roar. Or it didn’t. When it stalled at the bottom of the hill, my mother would get out and, to ‘save the battery’, effortfully swing the crank handle.

Granny’s house stood several streets short of the sea, up a sloping cul-de-sac. Past the gate, one had to climb a crazy-paving path flanked on either side by a rock garden of lavender and alpine plants. With its small bow-windowed drawing room at the front and whitewashed pebbledash, the house, I see now, was a very modest example of 1930s suburban bijou, but then I thought it grand and magical. Granny in the doorway, looking slightly top-heavy with her bosomy torso balanced on girlishly slender legs, dogs yapping behind her, smelled of eau de cologne and cigarettes. In every room there were open boxes of cork-tipped Craven A’s, the cigarettes nestling, close-packed, in their pillar-box red containers with the black cat logo. To me, Granny’s cigarettes were a sign of extraordinary opulence in the wartime world of shortages and rations.

On these visits, my mother would accept a cigarette when Granny offered, but anyone could see that she was an amateur smoker, breathing in and puffing out between coughs. Granny, though, was a professional: she could convey deep meditation with a drag, dismiss an argument with an exhalation, draw a protective veil of smoke around herself and deliver an oracular remark from behind it, extinguish a conversation and a cigarette in one gesture. She was a study in the rhetoric of smoking. She also had the fascinating knack of blowing smoke rings, for me only, when she was in the mood.

She had just turned fifty. Every expedition to see her was a treat for me, if a rather scary one, for Granny was the first person I knew to maintain a visible disconnect between what she said and how she really felt. Extravagant daily labour went into her appearance – the greying permed hair, the rouge and powder, the scent, the afternoon rests taken in her darkened bedroom, from which she emerged freshly dressed and in a new and unpredictable mood, along with her dogs, a pair of miniature Yorkshire terriers named Timmy and Charles who slept at her feet. Granny was a creature of artifice, and though she was always smiling, one couldn’t trust her smiles because there was often something wicked to be glimpsed behind them…

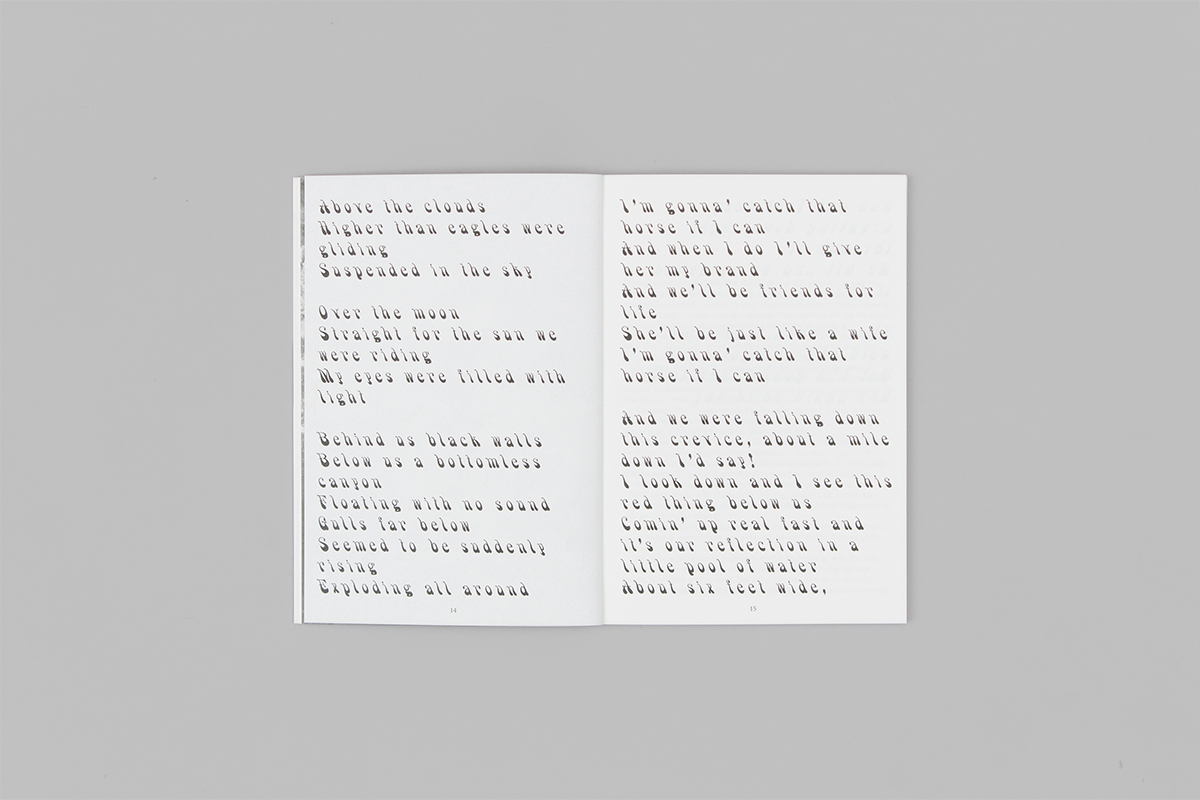

David Lynch interviewed by Mark Cousins on BBC’s Scene for Scene (1999)

Kleiner Feigling is a brand of naturally-flavoured fig liquor, made by BEHN in Eckernförde, Germany. The production of Kleiner Feigling started in 1992 and since then has reached annual worldwide sales of 1,000,000+ cases. The name translates literally to Little Coward and is a pun on the words feige (cowardly) and Feige (fig), which are homophones in German. In Germany, the drink is often purchased in 20 milliliter shooter-sized bottles. Custom dictates that the drinker tap the cap of the upside down bottle on the table, making bubbles in the liquid just before it is consumed.

Thomas Keymer on Autobiography

Thomas De Quincey invited comparison with Rousseau in Confessions of an English Opium-Eater, but relinquished Rousseau’s sense of personal control. The opium becomes a rival protagonist of his story, almost at times a rival author. It strips away the ‘veil between our present consciousness and the secret inscriptions on the mind’ and opens the narrative, in proto-psychoanalytic ways, to dream and unreason. De Quincey sees how strange it is to use an inherited literary model to express one’s own uniqueness, and at one point wonders if he might not in fact be ‘counterfeiting my own self’… Influential accounts of the genre like Laura Marcus’s Auto/biographical Discourses (1994) have emphasised the way identity seemed to fracture in literary modernism. Katherine Mansfield’s scepticism about ‘our persistent yet mysterious belief in a self which is continuous and permanent’; Louis MacNeice’s wry sense that ‘as far as I can make out, I not only have many different selves, but I am often, as they say, not myself at all.’ In Virginia Woolf’s remarkable ‘A Sketch of the Past’, drafted as she wrote her biography of Roger Fry, the gap between narrating and narrated selves – ‘the two people, I now, I then’ – proves recalcitrant and persistent, refusing to close. In any case, the self Woolf sought to document was not so much subject as object: not a self-determining agent but ‘the person to whom things happen’, acted on by immense, inscrutable social forces. To consider these forces, their power and their invisibility, is to realise ‘how futile life-writing becomes’, Woolf writes: ‘I see myself as a fish in a stream; deflected; held in place; but cannot describe the stream.’

Paul Goldberger quotes Peter Eisenman in a discussion of House VI, published in The New York Times Magazine, March 20, 1977.

…the house is not an object in the traditional sense–that is, the end result of a process–but more accurately the record of a process. The house, like the set of diagrammed transformations on which its design is based, is a series of film stills compressed in time and space. Thus, the process itself becomes an object; but not an object as an aesthetic experience or as a series of iconic meanings. Rather, it becomes an exploration of the range of potential manipulations latent in the nature of architecture, unavailable to our consciousness because they are obscured by cultural preconceptions.