Search for ‘MATT ’ (136 articles found)

Brian Dillon on 'Aspen'

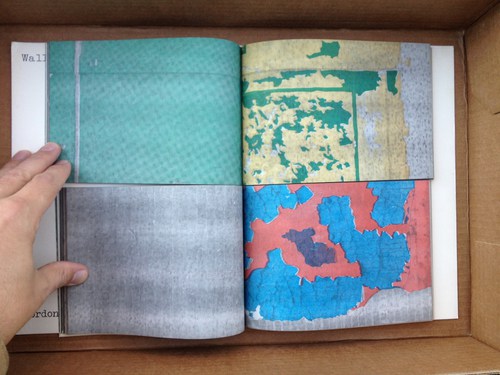

In August 1971 the US Postal Service wrote to Phyllis Johnson, the publisher of Aspen, an arts and culture quarterly then in its sixth year, to inform her that the magazine’s right to reduced postal rates had been definitively revoked. Aspen, which is the subject of an exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery until 3 March, seems to have fallen foul of Title 39 US Code 4354 on several counts, not least the journal’s increasingly intermittent publication schedule. There was the matter too of its eccentric form; whatever else it was, according to the Postal Service, a periodical was surely a discrete object made of printed sheets, bound together and maintaining more or less the same format from issue to issue. Aspen was a bureaucratically flummoxing proposition: an unpredictable agglomeration of essays and articles on loose pages or in booklets, packaged with flyers, photographs, diagrams, flexidiscs and even in one issue a spool of 8mm film – all housed in a box whose design and dimensions varied from one mail-out to the next.

Texts about yellowism

►► A mysterious place in the universe

On 7th of October 2012 yellowist Vladimir Umanets went to Tate Gallery and signed Mark Rothko’s painting “Black on Maroon” (from Seagram series). Tate Modern will remove (or removed already) Umanets signature and title: “A potential piece of yellowism”. Unfortunately, Tate will not keep the inscription and therefore will “deface” something very special. But, regardless of what Tate will do with it, Rothko’s painting will be always remembered as a potential piece of yellowism.

Rothko’s work of art, placed in Tate and signed by Umantes, is still a work of art, it is not a piece of yellowism. It is (only) a potential piece of yellowism which means that Rothko’s painting can stop being a work of art, and can become a piece of Yellowism – if Rothko’s painting was placed in a yellowistic chamber, then it wouldn’t be a work of art anymore, and would express yellow colour only; it would be a definition of yellow given in the form of Rothko’s painting. In other words: Rothko signed by Umantes is still in Tate Gallery therefore it is still a work of art – a work of art entitled: “A potential piece of yellowism”. This painting will be a piece of yellowism only in a yellowistic chamber, in the context of yellowism. It can (potentially) gain the new status. “A potential piece of yellowism” shows the possibility of transformation.

Rothko said his paintings begin an unknown adventure into an unknown space. I think that especially “Black on Maroon” with the title “A potential piece of yellowism” begins an unknown adventure into unknown space. The new context called Yellowism is still an unknown space for many people. Simon Schama (in “Simon Schama’s Power of Art – Rothko”) says about Rothko’s painting: “I felt I was being pulled through those black lines to some mysterious place in the universe.” Now, not the black lines painted by Rothko, but rather the black inscription on the Rothko’s painting: “A potential piece of yellowism” pulls the whole world, the whole public, and all people around the world, to the new “mysterious” place called “yellowism”. However, this new territory, this new intellectual field, is not so mysterious – it’s clearly defined. The definition of yellowism is not a secret.

You can look through “A potential piece of yellowism”to see the new context. If you resign from being an artist and you abandon the context of art – you don’t need to return to the context of everyday reality, because you have the possibility to discover the context of yellowism. You don’t have to step back, you have the opportunity to radically change your perception and see all and everything as expressions of yellow color only – including the beautiful “Black on Maroon” by Mark Rothko.

text by Marcin Lodyga

►► The Last Exhibition of Yellowism

Every yellowism exhibition is identical in content. Pieces presented on the first, the second or the legendary third exhibition of yellowism expressed exactly the same as pieces which could be presented at the fourth exhibition. Also, pieces on the fifth or sixth or thousandth exhibition of yellowism will be expressing the same. In the context of yellowism the content will never change.Yellowism expansion wants to transform all the existing minds into one flat surface and radically change the human perception. Every yellowism exhibition is the part of this expansion, expansion, no evolution. There is no progress, yellowists don’t develop any idea. Everything was finally defined at the very beginning ( of yellowism) therefore you should not expect any intellectual news on the next exhibitions. Every exhibition of yellowism which took place in the past and every future exhibition of yellowism is the last, the final. The past of yellowism looks like the future of yellowism. One can say that there is no past and there is no future in yellowism and the time is stopped.

text by Marcin Lodyga

►► Feelings

In the context of yellowism every feeling is a definition of yellow, every emotion expresses yellow color only. Sadness is about yellow and happiness is about yellow too. Pain is considered as a pure expression of yellow, orgasm as well. Inside the context of yellowism all emotions and feelings captured on the four pictures (above) and emotions and feelings which these images can arouse in potential viewers, express yellow color and nothing more.

text by Marcin Lodyga

►► Listen to Young Dictators

Consider yellowism as a totalitarian system. Two young “dictators” – authors of the definition and manifesto of yellowism decided that there is only one interpretation in this specific context. Everything is about yellow – this is the order, the final solution. It is imposed on you, you are not free to interpret, and you have to accept the only possible way of seeing things. This way and no other way. If you don’t want to accept the fact that in yellowistic chambers you can see only pure expressions of yellow color – don’t worry, the young “dictators”: Lodyga and Umanets will not send you to a gas chamber (btw if a gas chamber was placed inside a yellowistic chamber then it would be about yellow). If you try to reject the existence of the new phenomenon then better just go back to your ordinary reality or go to an art gallery where you can enjoy the diversity of meanings, symbols and references.

text by Marcin Lodyga

►► One and Many

“Abstract painting is abstract.” – Jackson Pollock “The flight from interpretation seems particularly a feature of modern painting. Abstract painting is the at tempt to have, in the ordinary sense, no content; since there is no content, there can be no interpretation. Pop Art works by the opposite means to the same result; using a content so blatant, so “what it is,” it, too, ends by being uninterpretable.” – Susan Sontag, “Against Interpretation” Yellowism is not against interpretation, but Yellowism gives only one interpretation. Not many, just one, forever. Every piece of Yellowism is about yellow and nothing more. Whatever you put into a yellowistic chamber, it is a definition of yellow. The lack of many different interpretations is not the lack of interpretation. Every piece of yellowism has the content – every piece of yellowism has exactly the same content. All pieces of yellowism are interpretable because all are about yellow and express yellow, however the content is not obvious (blatant) for humans. Humans have a problem to see beings and objects (inside yellowism) as expressions of yellow color only. If for humans the fact that inside yellowism everything is about yellow was obvious and blatant, then it would mean that human perception was radically changed. An abstract painting placed in a yellowistic chamber has the content – the same content as a chair or anything else placed in a chamber . Every abstract painting (inside yellowism) is a definition of yellow, therefore is not so abstract anymore because you can see (interpret) it as a pure expression of yellow color. In art, an abstract painting is the at tempt to have, in the ordinary sense, no content.

text by Marcin Lodyga

►► Oh My God!

A monkey doesn’t distinguish between contexts. A monkey jumps on a chair in an apartment – in the context called reality, ordinary reality where objects are useful. A monkey jumps on a chair placed in an art gallery ( in the context of art) where a chair has meanings, a sense, a chair can be, for example, about love, war, death, existence, art itself etc and can expresses a lot of different things. But monkey doesn’t see any sense when looking on a chair; it jumps on a chair like in an apartment. Also, a monkey jumps on a chair in a yellowistic chamber, it doesn’t see that a chair in the context of yellowism is about yellow and expresses yellow color only. That’s obvious that a monkey doesn’t see differences between ordinary reality, art and yellowism; it just want to jump (or sit in a funny monkey way) on a chair, doesn’t matter where. But you, do you see the difference? It’s time to clearly and radically distinguish between contexts. Even if sometimes the context of art matches the context of reality or borders between them are very blurred, you still need to know what art is and what everyday reality is, also you have to know what yellowism is. Hypothetically, if one day art equals reality and therefore there is no art and no reality anymore, yellowism will be still a different context, a separate territory. According to polish theoretician and visionary Jerzy Ludwinski, the evolution of art can reach the stage called “the stage of totality” and this is how he described it: “What matters are the tensions created by the collective effort of many individuals which contributes to the making of one system, pulsating with its own life like some gigantic work of nature. Art = reality.” Even if there was such a fusion (art + reality), yellowism would be still “outside”. If art disappeared and reality disappeared – if both were transformed into “aRteality” or something like that, I would call yellowism, it this particular case, not the third but the second context. If two contexts (art and reality) become one, then the third context we should perceive as the second context. Imagine that yellowism is the only context which exists and you don’t need to distinguish anymore. No art, no ordinary reality (no “aRteality” as well), just yellowism, the whole universe is like one huge yellowistic chamber, all and everything is flattened to yellow. What would you say in a such ontological situation? Will you say: “Oh my god!”?

►► The Nature of Yellowistic Drafts

A yellowistic draft is not a piece of Yellowism. A yellowistc draft becomes a piece of Yellowism when you insert it into a yellowistic chamber and then, like every piece of Yellowism, is about yellow color, expresses yellow color and nothing more. There are two types of drafts: drafts that were made during the period of transition between art and Yellowism (June – November 2010, Cairo), and drafts which were made after the writing of the Manifesto of Yellowism. The first ones were made parallel with the manifesto and were the notes (in various forms) relating to the different ideas that occurred at the time when we were defining Yellowism. These drafts were comments on the manifesto. After the Manifesto of Yellowism almost anything can become a yellowistic draft if yellowist chooses it and sign it. Any being, any object from the surrounding reality can get the status of a yellowistic draft. Yellowists can choose one draft from the set of yellowistic drafts and transform it into a piece of Yellowism. Yellowist makes yellowistc drafts and thus show what and who can be flattened to yellow. A yellowistic draft is a potential piece of Yellowism. Yellowists indicates all that what can be about yellow color and at the same time they also show how full of meanings, symbols and references is a draft before the “flattening” in a chamber. Draft may induce multiple interpretations and can be decoded in similar way as work of art can be, but of course a yellowistic draft is not a work of art. Some people will say about drafts: “Oh, it might be an interesting and beautiful work of art” or “I would like to show it in a gallery where art critics would admire it”. Those who want to perceive yellowistic drafts in this way, will always be disappointed because a yellowistic draft is just a yellowistic draft and at any time can be positioned in a yellowistic chamber and thus can be deprived of its intellectual richness. Titles of yellowistic drafts can only intensify a pain of those who wish to keep contents, because a title which magnifies a field of interpretation, loses its significance in a yellowistic chamber; a title is no longer a source of new meanings. No matter how you title a piece of Yellowism, it is about yellow anyway. Some yellowistic drafts will never become pieces of Yellowism. There are also pieces of Yellowism, which previously were not yellowistic drafts.

text by Marcin Lodyga

The protagonist of this story has no name. It is known simply as the Chicken, a nonname that seems right, considering its obscure origins. How it came to a small backyard in Astoria, Queens, remains a matter of conjecture. The chicken made its first appearance next door, home to a multitude of cabdrivers from Bangladesh. My wife, Nancy, and I decided that they had bought the chicken and were fattening it for a feast. That hypothesis fell into doubt when the chicken hopped the fence and began roaming around our yard. It began pacing the perimeter of the yard with a proprietary air, sizing things up with a shiny, appraising eye that said, I’ve seen better, but I’ve seen worse.

We now had a chicken. Very nice. But what next?

Eating it was out of the question. As a restaurant critic and an animal lover, I subscribe to a policy of complete hypocrisy.

Decoy. Chrisopher Specce. Sapele and maple, 10” × 5” × 7.5”.

Sargent, 'Robert Louis Stevenson and His Wife' (1885)

Oil on canvas, 52.1 × 62.2 cm. Private collection.

Stories from the New Aesthetic

James Bridle is fond of a satellite photograph of the border between Namibia and South Africa — in the middle of a desert, alongside the Orange River, there are two blocks of shimmering green pixels. They’re actually very tidy rectangular fields, but Bridle holds that, to today’s eyes, its difficult to see this gridded pattern of monochrome shades as anything other than pixels.

This variety of paradox was at the center of “Stories From The New Aesthetic,” the penultimate discussion in a series put on by Rhizome, at the New Museum.

The three speakers — Aaron Straup Cope, of the Cooper-Hewitt; Joanne McNeil, editor of Rhizome; and Bridle, the writer who coined “the New Aesthetic“ (but is quick to point out that he’s not proud of the phrase) — spoke of their increasing awareness of, and developing attitudes about, the integration of technology and everyday life. Specifically, the way they begin to behave when they overlap or reflect each other.

The fact that satellite imagery and fairly precise GPS location is readily available for anyone with a new phone might be commonplace, but the scale of that realization, both in terms of its global ubiquity and the complexity of the necessary support system becomes dumbfounding in even a larger historical frame. Only a few decades ago, the nuclear-powered submarines of the two most heavily invested militaries the world has ever known could not target ballistic missiles acceptably because, on a basic level, the submarines couldn’t even tell exactly where they were.

The now-continuous intersection between the physical world and its computer representations was the starting point for the three highly caffeinated imaginations on display at the New Museum. Cope, previously a geolocation engineer at Flickr, dilated on the echoes of reality and its schematic representation: reflections piling upon each other, and sets of overlapping data becoming increasingly rife with meaning — intended and otherwise. The complexity of possible interpretations led to a comparision of the eery oscillations of elevator statistical recordings and undersea whale calls. In such cases, the mapping of patterns against each other can often go awry. When this happens on the machine side, the feedback loops and glitches generated can seem to offer new worlds to human perception.

Bridle was struck by a list of the most productive editors on Wikipedia — presently the human race’s most exhaustive single reference resource — in which the majority were, in fact, robots. Especially in the most frequently-used networked interfaces, the pattern-matching of machines in bits of software appears to intimately interpenetrate with our own forms of recognition. The slippage between the two can be powerfully disorienting as well: in Bridle’s project Where The Fuck Was I? he unlocked his iPhone’s logged GPS data, which had traced his location in a kind of geographical diary for the previous year. But, as he explained in the discussion, he noticed later that there were places logged that he couldn’t have been — hovering above the Thames, perhaps — that were rather the product of phone’s heuristic means of locating itself:

It’s finding itself according to a whole network that we can’t really perceive. This is an atlas made by robots that is not just about physical space, but is about frequencies in the air and the vagaries of the GPS system. It’s an entirely different way of seeing space.

Joanne McNeil approached the mysteries of robot vision from the opposite direction: she observed that Google Maps’ anonymized faces are animated by their ambiguity, their strangeness heightened by their appearance in frozen, starkly exposed physical spaces. A similar kind of imposed narrative arose from Apple’s recent map update, in which its warped topology gave birth to structures and locations that seem to melt into puddles or crawl in jagged zig-zags across a plane. While these errors can be looked at solely as hazards for navigation, McNeil argued they can also be seen as seams through which the narrative of the human “way of seeing” compares to a machine’s.

There is such a preponderance of the “beauty of glitches” in talk of the New Aesthetic that it’s easy to start to think that’s simply what the phrase refers to. But it seemed to me the range of examples is not so easily circumscribed. Similar projects like Jon Rafman’s 9 Eyes — a collection of wide-angle images snapped in Google Street View — tend to be driven by what Henri Cartier-Bresson called “decisive moments.” On occasion they come from the distorions of space or color that affect the Google camera at critical angles, but mostly they are moments frozen in an instant of heightened significance: a nude standing by the shore, a band of wild horses glimpsed behind ancient gravestones. Their beauty arises almost entirely from the strictly human elements of their contents.

The term might seem to better suit Greg Allen’s reprinting of “Wohlgemeynte Gedanken über den Dannemarks-Gesundbrunnen”, in which a 2008 Google Books scan rendered an 18th-century treatise on “hydrologie” into impressively flowing and rippling typographical landscapes. Released as an eBook, Allen’s piece navigates a turbulent space between printed matter and digital representation, from the accident as an artistic origin and the unknowable logic of a failing optical scanner. But again, its force derives from the reflexivity of its maker, and the object’s pose within established codes of art-making and visual beauty.

The talk surrounding The New Aesthetic urged some further level of comprehension or intermeshing of human and machine modes of understanding. (At times during the talk, I felt alone in my doubt about whether present-day machines can be said to “understand” in any sense that retains the word’s meaning.) If the New Aesthetic is to metabolize the kinds of refraction and layering between codes and languages — or ways of seeing — it seemed to me its examples ought to emerge not from happy coincidence, but rather from the explicit, perhaps eery, echoes between different worlds.

What seemed to go unsaid, or perhaps was implicitly rejected, was the established complaint about the portal of representative technology, first made by philosophers like Jean Baudrillard and Umberto Eco, for whom representation and distancing were forms of impoverishing “the real.” A new form of this disappointment was expressed by the anthropologist David Graeber in a recent essay for The Baffler:

The technologies that have advanced since the seventies are mainly either medical technologies or information technologies — largely, technologies of simulation (…) the only breakthroughs were those that made it easier to create, transfer, and rearrange virtual projections of things that either already existed, or, we came to realize, never would (…) The postmodern moment was a desperate way to take what could otherwise only be felt as a bitter disappointment and to dress it up as something epochal, exciting, and new.

The most profound suggestion behind all the various limbs of the New Aesthetic is that something new can be found not just in linear progress through “the real” (which perhaps might be better put as simply “the material”). It might be found, instead, in the strange undertones in the resonance between the way a representation is automatically generated and the way we have come to think of it in the complacency of our ordinary material existence.

That point of intersection — between representation and reality — is, after all, where art has always found meaning. Bridle stressed that, to truly understand that hall of mirrors as it exists today, we must search these systems for the keys to unlock them from the inside, before they will be comprehensible, first we must “find the right metaphors.” Though Theodor Adorno may well have been dismayed at these prospects, I think one of his instructions remains apt: “Teach the petrified forms how to dance by singing them their own song.”

From the critical writings of Ford Madox Ford

[Joseph Conrad and I] agreed that the general effect of a novel must be the general effect that life makes on mankind. A novel must therefore not be a narration, a report. Life does not say to you: In 1914 my next-door neighbour, Mr. Slack, erected a greenhouse and painted it with Cox’s green aluminum paint…. If you think about the matter you will remember, in various unordered pictures, how one day Mr. Slack appeared in his garden and contemplated the wall of his house. You will then try to remember the year of that occurrence and you will fix it as August, 1914, because having had the foresight to bear the municipal stock of the City of Liege you were able to afford a first-class season ticket for the first time in your life. You will remember Mr. Slack — then much thinner because it was before he found out where to buy that cheap Burgundy of which he has since drunk an inordinate quantity, though whisky you think would be much better for him! Mr. Slack again came into his garden, this time with a pale, weaselly-faced fellow, who touched his cap from time to time. Mr. Slack will point to his house wall several times at different points, the weaselly fellow touching his cap at each pointing. Some days after, coming back from business, you will have observed against Mr. Slack’s wall…. At this point you will remember that you were then the manager of the fresh-fish branch of Messrs. Catlin and Clovis in Fenchurch Street…. What a change since then! Millicent had not yet put her hair up…. You will remember how Millicent’s hair looked, rather pale and burnished in plaits. You will remember how it now looks, henna’d; and you will see in one corner of your mind’s eye a little picture of Mr. Mills the vicar talking — oh, very kindly — to Millicent after she has come back from Brighton…. But perhaps you had better not risk that. You remember some of the things said by means of which Millicent has made you cringe — and her expression! … Cox’s Aluminum Paint! … You remember the half-empty tin that Mr. Slack showed you — he had a most undignified cold — with the name in a horseshoe over a blue circle that contained a red lion asleep in front of a real-gold sun….

And, if that is how the building of your neighbour’s greenhouse comes back to you, just imagine how it will be with your love affairs that are so much more complicated….

At Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin

In the long warehouselike Rieckhallen extension at the Hamburger Bahnhof, curator Gabriele Knapstein’s current group show explores how architecture both structures and delimits urban life. A series of bright, high-ceilinged rooms showcase spatial experiments (such as Sol LeWitt’s Modular Cube, 1970) flanked by photographs and architectural drawings. Dan Graham’s “Homes for America” series, 1972, like LeWitt’s cube, interrogates regularity and, in a different way, whiteness. More fervent dissections of homes are undertaken by Gordon Matta-Clark, and, a little surprisingly, they hit a common chord with Thomas Struth’s large-scale ruminations on Tokyo and Paris in the turbulent 1980s, which anatomize not a facet of architectural space but its physical experience.

Along the way there are several dimmer compartments containing hopeful architectural plans. Walter Jonas’s model for funnel-shaped Intrapolis, 1960, recalls an inverted version of Bruegel’s Babel. Peter Cook, of English design group Archigram, hits upon a similar design for his drawings for Plug-In City, 1964, a complex superstructure intended to accommodate itself to any terrain. The morphological paradox of architecture—concrete, often rectilinear structures for fickle, often round inhabitants—is most spectacularly reconciled in the rangy, ongoing Gartenskulptur (Garden Sculpture), 1968–, Dieter Roth’s meditation on the conditions of life and decay—a living, breathing Gesamtkunstwerk of bric-a-brac.

The least utopian but perhaps most convincing of these visions can be found in a screening room downstairs. Anri Sala’s video Dammi i colori (Give Me the Colors), 2003, scrolls through oneiric images of spectacularly painted, primitive buildings as the voice of Edi Rama, former mayor of Tirana, floats over the darkness. The capital’s crude, brutal architecture, he explains, is balanced by a wandering, riotous palette. Indeed, the citizens have painted Tirana’s buildings without regard to property boundaries—or neighbors. This anarchic yet clearly delineated attitude—like the well-sorted chaos of Roth’s interactive garden—is most comfortable with an understanding of the built environment not as a solution to a problem, but as an ongoing process of evolution.

The bubble

It’s the first time a sitting President has ever appeared at the Apollo, and people are here to show Barack Obama that they’ve got his back[…] There is something special about this event for Obama, which shows up in the way he torques familiar lines, making them shorter and punchier, and a touch more idiomatic. “When you decide to support somebody named Barack Hussein Obama for president, you’re not doing it because you think it’s a cakewalk,” he says—cakewalk being a perfectly good word to use in place of easy and also a word that has a particular resonance for an older black audience. The name of an ancient ragtime step with its roots in slavery days, cakewalk conveys a sense of movement and of foolish pride, as in the “cakewalk strut,” an evolution of the dance. Sitting in the dark of the Apollo, I understand something new about Obama’s relationship to blackness—namely, that the emotion behind his performance of his own identity is entirely authentic, even as he understands race as a cultural construct. There is something wonderfully strange about having a president who can give evidence of functioning on so many levels at once. For a moment I think about whether the people who give money to his campaign are paying for the same rarefied and self-flattering moment of pleasure, or whether he provides subtly different but similarly exclusive moments to different donors.

“You did it because you understood the campaign wasn’t about me,” he says, speaking out into a dark space filled with living people who he recognizes as being like himself, in a dimension that he doesn’t share with the people at Daniel. “It was a vision that was big and compassionate and bold, and it said, In America, if you work hard you’ve got a chance. You got a chance to get ahead,” he says, his voice taking on that folksy edge that during the 2008 campaign made him sound like some nerdy black kid in a sweater-vest imitating Bill Clinton. Maybe it took a while for us to get used to hearing him plain, or maybe he is more confident in himself now, or more confident in his audience. Or maybe this trajectory was alive in his mind the whole time. Artificial and also in many ways inevitable, the resulting fusion of the social category of race and his own experience of loss and pain dissolved an emotional paradox in a way that carries deep and continuing meaning for him, and that he is afraid to touch […]

Then it was off with Bill Clinton to the Grand Ballroom of the Waldorf, where Jon Bon Jovi did an acoustic version of “Living on a Prayer” followed by the Beatles’ “Here Comes the Sun.” At the New Amsterdam Theatre, there is a reading of quotations from Walt Whitman, Gary Shteyngart, and John Updike, who is credited with the line “America is a vast conspiracy to make you happy,” which proves, I am sad to admit, that one of America’s greatest prose artists of the later twentieth century was also something of a moron. The curtain comes down at the end of the first act, and Stevie Wonder’s “Higher Ground” comes on again, a song that Barry Obama most likely did roof hits to with the Choom Gang while playing hooky from Punahou.

The fact that the President was a stoner in high school is only one of the many things I like about him, I am thinking, as my attention wanders over to Bill Clinton, the guy who didn’t inhale. So much has happened since he left office—9/11, Iraq, the iPhone, the financial implosion. Silver-haired, standing in front of the American flag, he looks like an escapee from Madame Tussauds. “You know, I was worried about getting half a step slow doing this,” Clinton admits, adding, “I’m a little rusty at politics.” Say it ain’t so, Bill, you sly dog you. But there is a reason Clinton is here today with Obama—aside from their common goal of getting money from Marc Lasry.

“I know things are not perfect now,” he says. “I know they’re a little slow now.” The giveaway is that he repeats the line: he likes the fact that things are slow. It makes him look good and Obama look bad. “Starting on September the fifteenth, we entered the deepest crash since the Great Depression,” he helpfully explains. My mind wanders away from the predictable scene of the wily Clinton undermining his young successor and settles on his hair. Bill Clinton’s hair has star quality. His silver mane is so textured and gorgeous, there’s no way he’s ever going back to Little Rock for a haircut. “If you look at history, those things take five or ten years to get over,” he is saying, “and if there’s a housing collapse along with it, closer to ten years. He’s on schedule to beat that record.” Later, summing up, Clinton looks out at the crowd of 1,700 true believers, most of whom coughed up $250 per ticket for a glimpse of the President and a passel of show tunes. He bites his lip, searching for a surefire way to clinch the deal.

“He did the best he could with a lousy hand,” he offers. I can see the campaign bumper sticker now: He Did The Best He Could With A Lousy Hand. Paid For By Obama/Biden 2012. Print it, folks! “Give us a twenty-first-century economy we can all be a part of,” Clinton urges, showing us that it is possible to do the big-think reframing thing that Obama is too chicken to try. It’s not you, Bill, I am thinking. It’s the pictures that got small.

At 10 P.M. sharp, Obama walks onstage to rousing applause and starts to speak, while Clinton sits ten feet away from him on a chair and runs through active-listening poses, seamlessly transitioning from one to another, like an adept of Vinyasa yoga. There is Richard Branson pose, and Bono pose, and Dominique Strauss-Kahn pose, honed at countless global seminars on poverty and microlending in Africa. I absorb knowledge like a sponge, which is why in 2016 I will be elected secretary-general of the U.N., which by then will be the most important job in the world, if for no other reason than the fact that it will belong to me, Bill Clinton. I’m ready, folks. But Obama can’t stand me. He made Hillary secretary of state in order to cut my balls off. Now he wants me to pull his irons out of the fire, and I think the best way to do that is to tell the truth, which is that Obama is at least a medium-size stack of hundreds better than the millionaire Mormon leveraged-buyout stiff who wants to be president of “Amercia.”

Obama turns to face Clinton, his political father, or at least the father of the Democratic Party to which he is heir. “Shortly after I had been elected—Bill can relate to this,” he says, “the Secret Service bubble shrinks and it starts really clamping down.” The crowd laughs, glad to be included in the amiable dialogue between these two masters of the political universe and wondering what is coming next. “And the thing that you miss most when you’re president—extraordinary privilege, and a really nice plane, and all kinds of stuff,” Obama says, as if suddenly recollecting that there are some good things about the job, “but suddenly, not only have you lost your anonymity, but your capacity to just wander around and go into a bookstore, or go to a coffee shop, or walk through Central Park.”

He is talking half to himself and half to Bubba, who also understands the bubble. “So I was saying,” he continues. “It was a beautiful day and I had just been driving through Manhattan, and I saw Margo,” he says, referring to one of the producers of Barack on Broadway, the estimable Margo Lion, winner of no fewer than twenty Tonys. “And I said, you know, I just desperately want to take a walk through Central Park again, and just remember what that feels like. But the problem is, obviously, it’s hard to do now.” He asked Margo Lion for help, he says, and about a week later he received a fake mustache. “And I tried it on and I thought it looked pretty good,” he says, as the crowd laughs. “But when I tested this scheme with the Secret Service, they said it didn’t look good enough. But I kept it,” he adds. “So if a couple years from now you see a guy with big ears and a mustache”—the crowd laughs—“just pretend you don’t know who it is. Just look away”—the crowd laughs harder—“Eating a hot dog, you know.”

It’s an unusually personal anecdote for one of these events, a soft-shoe fantasy of disguise and escape presented as a harmless bit of persiflage. The internal suggestion that in order to appear normal he must disguise himself is always there, and has had a negative effect on his presidency. “It doesn’t matter where you come from, what you look like, whether you’re black, white, Hispanic, Asian, Native American, gay, straight, able, disabled—it doesn’t matter,” he says. “You’ve got a stake in this country,” he says. “You’ve got a claim on this country.” Clinton massages his chin and then freezes the pose, presenting himself as a sculptural form, The Listener. Which one is it, a stake in or a claim on? That Barack Obama is a weird cat. That racial shit will fuck anyone up. He drops both his hands to his lap to give the audience the straight profile, Clinton Rex.