Search for ‘MATT ’ (136 articles found)

Richard Rorty on Saul Kripke, 2005

As I see it, Kripke’s lectures in 1970 aroused the interest they did not because people cared all that much about which truths should be called necessary and why, but because they cared a lot about whether truth is correspondence to reality. Philosophers are still, just as they were in Russell’s day, very worried about whether there is any clear sense in which our beliefs about the world are like maps – whether they are somehow isomorphic to the pre-existing contours of reality (whether, in Plato’s metaphor, they ‘cut nature at the joints, like a good butcher’).

Common sense takes for granted that there is such isomorphism – that just as bits of a reliable map can be paired off with bits of a landscape, so the terms of a true scientific theory can be correlated with features of the way things really are. But those who think that all essences are nominal point out that such pairing was easier when, as in Aristotle’s time, the objects of scientific inquiry were observable things such as stars and animals. It got harder when Newton began talking about unobservables such as force, mass, and acceleration, and harder still when Planck began talking about quanta. Is ‘force’ the name of a natural kind? Is ‘Hilbert space’? Do these terms cut nature at the joints? Who knows? How could it matter? The more unobservables science posits, the less relevant the notions of ‘mapping’ and ‘corresponding to reality’ seem.

However, many philosophers fear that if we cannot specify some sense in which our scientific theories map onto reality in the same way as do perceptual reports (‘the cat is on the mat’), we are in danger of losing touch with the world. We may be tempted to become instrumentalists, people who think that we should accept scientific theories simply because they give us what we want (roughly, prediction and control of the environment), rather than because we think they accurately represent the real. For those who had such fears, Kripke’s neo-Aristotelian outlook had great appeal. Quine’s holistic claim that ‘the unit of empirical significance is the whole of science’ (rather than individual words or sentences) had done a lot of damage to the notion of ‘correspondence’. So had Kuhn’s denial that scientific progress is a matter of getting closer and closer to the true nature of things. Kripke’s willingness staunchly to oppose the drift toward pragmatism that characterised analytic philosophy during the 1960s won him an enthusiastic audience.

From Robert Walser's 'Berlin Stories' (1907; t. Susan Bernofsky)

A lager please! The tap man’s known me for ages. I gaze at the filled glass a moment, take it by the handle with two fingers, and casually carry it to one of the round tables supplied with forks, knives, rolls, vinegar, and oil. I place the sweating glass in an orderly fashion upon the felt coaster and consider whether or not to fetch myself something to eat. This food-thought propels me to the blue-and-white-striped cold-cuts damsel. I have this lady serve me a plate of assorted open-face sandwiches and, thus enriched, trot rather indolently back to my seat. Neither fork nor knife do I use, just the mustard spoon, with which I paint my sandwiches brown before inserting them so cozily into my mouth that it is perhaps tranquility itself to witness this.

Another lager please! At Aschinger, you quickly adopt a familiar food-and-drink tone of voice; after a certain amount of time there, a person can’t help talking just like Wassmann at the Deutsches Theater. Once you have your fist around your second or third glass of beer, you’re generally driven to engage in all manner of observations. It is imperative to note with precision how the Berliners eat. They stand up as they do so, but take their own sweet time about it. It’s a myth that in Berlin people only bustle, whizz, and trot about. People here have a nearly comical understanding of how to let time flow by; after all, they’re only human. It’s a sincere pleasure to watch people fishing for sausage-laden rolls and Italian salads. The payment is extracted mostly from vest pockets, almost always just a matter of small change.

Now I’ve rolled myself a cigarette, which I light at the gas flame beneath its green glass shield. How well I know it, this glass, and the brass chain to pull on. Famished and satiated individuals are constantly swarming in and out. The dissatisfied quickly find satisfaction at the beer spring and the warm sausage tower, and the satiated dash out again into the mercantile air, each generally with a briefcase beneath his arm, a letter in his pocket, an assignment in his brain, firm plans in his skull, and in his open palm a watch that says the time has come. In the round tower at the center of the room reigns a young queen, the sovereign of the sausages and potato salad—she’s a bit bored up there in her quiver-like surrounds. An elegant lady enters and with two fingers skewers a roll spread with caviar; at once I bring myself to her notice, but in such a way as if being noticed were of no concern to me at all.

Meanwhile I’ve found time to lay hands on another beer. The elegant lady is somewhat hesitant to bite into the caviar marvel; of course I immediately assume it to be on my account and none other that she is no longer fully in control of her masticatory senses. Delusions are so easy and so agreeable. Outside on the square is a racket no one really hears: a tumult of carriages, people, automobiles, newspaper hawkers, electric trams, handcarts, and bicycles that no one ever really sees either. It’s almost unseemly to think of wanting to hear and see all these things, you’re not new in town. The elegantly curved bodice that was just nibbling bread now quits the Aschinger. How much longer am I planning on sitting here anyhow? The tap boys are enjoying a calm moment, but not for long, for here they come rolling in again from out-of-doors to throw themselves thirstily upon the bubbling spring.

Eaters observe others who are similarly working their jaws. While one person’s mouth is full, his eyes can simultaneously behold a neighbor occupied with popping it in. And they don’t even laugh; even I don’t. Since arriving in Berlin, I’ve lost the habit of finding humanity laughable. At this point, by the way, I myself request another edible wonder: a plank of bread bearing a sleeping sardine upon a bedsheet of butter, so enchanting a vision that I toss the whole spectacle down my open revolving stage of a gullet. Is such a thing laughable? By no means. Well, then. What isn’t laughable in me cannot be any more so in others, since it’s our duty to esteem others more highly than ourselves no matter what, a worldview splendidly in keeping with the earnestness with which I now contemplate the abrupt demise of my sardine pallet.

A few of the people near me are conversing as they eat. The earnestness with which they do so is appealing. As long as you’re undertaking to do something, you might as well set about it matter-of-factly and with dignity. Dignity and self-confidence have a comforting effect, at least on me they do, and this is why I so like standing around in one of our local Aschingers where people drink, eat, talk, and think all at the same time. How many business ventures were dreamed up here? And best of all: You can remain standing here for hours on end, no one minds, and not one of all the people coming and going will give it a second thought. Anyone who takes pleasure in modesty will get on well here, he can live, no one’s stopping him. Anyone who does not insist on particularly heartfelt shows of warmth can still have a heart here, he is allowed that much.

William James on careers

William James believed that the careers we might have chosen don’t matter very much: ‘Little by little, the habits, the knowledges, of the other career, which once lay so near, cease to be reckoned even among his possibilities. At first, he may sometimes doubt whether the self he murdered in that decisive hour might not have been the better of the two; but with the years such questions themselves expire, and the old alternative ego, once so vivid, fades into something less substantial than a dream.’

There are not too many left

Julius’ makes a strong claim to be one of the longest-running gay bars in the city, if not the oldest, and it is housed in an 1826 building at the corner of West 10th Street and Waverly Place. The walls are covered with articles and memorabilia. Tables are made from barrels stamped with the name of Jacob Ruppert’s Brewery, long vanished from Third Avenue in Yorkville. Julius’ was ancient and charming when Mr. Bourscheidt first visited in 1965 while a student at Columbia University.

“It was not so unusual in those days to find a bar that was filled only with men,” Mr. Bourscheidt said. “It was quietly known in the gay world as a gay bar. They did everything they could to conceal that fact. In my somewhat distorted recollection from 1965, it seemed that everyone in there had gone to Yale, was dressed in a suit, and was in advertising — which was then an occupation open to gay men, unlike banking or the law.”

Around his third or fourth visit, he bought a beer and turned from the bar to look around. The bouncer came over and told him it was New York State law that he had to face the bar. “I said, what kind of law is that?” Mr. Bourscheidt said. “It was the only time in my life I’ve ever been thrown out of a bar.”

That may have been a bizarre interpretation of a provision of the state liquor law that forbade the service of liquor to disorderly people — a group to which homosexuals, in the view of the State Liquor Authority, automatically belonged, regardless of decorum. This was challenged in 1966 by an organization of gay men, the Mattachine Society. Three men from the group appeared at Julius’ with a letter announcing their sexual orientation and their intention to remain orderly. Refused service at Julius’, they brought a court case and the law was overturned.

Until recent years, Julius’ catered mostly to an older crowd in the evenings, though it also served another clientele early in the day: longshoremen who had to shape up at a union hall downtown early in the morning, and were often sent home by 7:30 a.m. They would go directly to Julius’, said Dave Hunt, who worked at bars in the Village during the 1970s and now runs Coogan’s in Washington Heights. “They’d be up at Julius’ by 8 in the morning,” Mr. Hunt said, “and they were done and dusted by 11:30.”

Ms. Buford and her husband, Eugene Buford, bought Julius’ 13 years ago, and she took over the operation after his death three years ago. It has become a stop for people visiting historic spots in the Village, and a younger group of artists and writers meets once a month there. “People are discovering this gem in the Village,” Ms. Buford said. Mr. Bourscheidt said: “I hadn’t been there for years until recently, but it has been going through a resurgence.”

Julius’ has never been known for hygiene — it was known as Dirty Julius’ for its blackened ceiling in the years after Prohibition — and was shut down two years ago by the health department. The inspection last week found mouse droppings and an infestation of cockroaches.

Ms. Buford did not argue that there were problems that needed to be fixed, and said the bar had multiple exterminations over the weekend. But the timing was unfair, she said. “Friday afternoon before a holiday,” she said, meaning she could not get reinspected or reopened until after the weekend, which included New Year’s Eve.

Mr. Hunt said he was sympathetic to the owners, and also to Julius’ as an institution. “We must all support longshoremen/gay bars,” he said. “There are not too many left.”

What I Didn’t Write About When I Wrote About Quitting Facebook

The first thing I didn’t write about quitting Facebook was a status update to my friends saying, I’m quitting Facebook.

I also did not write a proposal for the nonfiction book I imagined, which was about quitting Facebook. In the book, I would indulge the conceit that my Facebook friends are, actually, my good friends, and that the social network comprises a sort of community when taken as a whole. Then, as one does with one’s friends, I would call each person up or visit them and tell them I was leaving Facebook, which would create an opportunity to talk about Facebook and this whole social media thing, but mainly it would be to get to know something about who they actually were and why we were linked in the first place and what it all might have meant.

Eighteen weeks of five interviews a day would get me through my friend list, I calculated. Friends from high school and college and grad school. Friends of friends. Editors. Siblings and a couple of cousins, my in-laws. Random admirers and hangers-on. The resulting book would reflect our conversations about how much Facebook had enhanced our friendships and our lives in general, or maybe it hadn’t, and we’d talk about that, too. And we’d exchange info, and say goodbye, and then linger, and wave, and wave, until we couldn’t see each other any more — one of those departures where you look away out of exhaustion with the moment, then when you look up find they’ve gone, vanished, as if they hadn’t been there at all.

At the end of the book, I would actually unplug from Facebook, and I would write about that, too, and the heartwarming account of the ties that bind us would inspire you to hold your Facebook friends close, so close, because the time we pass in this mortal coil is so fleeting; we are truly encountering only the passing of the person, not the person in themselves.

But I didn’t write this, nor did I write a status update about leaving. When I quit, there were no goodbyes. No interviews. Just, I’m outta here.

Another thing I did not write about quitting Facebook was that one of the great social pleasures in my life has been to leave gatherings or parties unannounced. You know, when the party is socked in solid from the front door to the kitchen, and the conversation is drying up like old squeezed limes, it’s easiest to keep heading out the back. How cool the night. How open and unquestioning the darkness. “French leave,” we English speakers say. (“English leave,” the French say.) Often I went to parties to be able to vanish from them. But the disappearing act rarely happens any more; I could never get away with it. Such pleasures one has to give up because they’re so unsuited to middle-aged life. You get trained, after a while, to going to every person in the room. Hey, great to see you again. See you later. Send me a note about that thing. Yes, let’s do that. Goodbye, bye. The book idea was, in a way, testing out the durability of that social grace. But I didn’t write about either topic.

I did, however, start an essay that could have been about why I quit Facebook, except that I got distracted by the emergence of a genre you could call the Social Media Exile essay, and I wondered whether I could meet the conventions of that genre if I ever tried to write about why I quit Facebook, though the truth is, I didn’t really want to write another version of the Social Media Exile Essay, dramatizing the initial promise of this or that social media or network, the enthusiastic glow of online togetherness, then the disillusionment, the final straw, the wistful looking back. I did write that it seems like so many people have had their crack at “The Day I Quit Blogging” or “Why I Tweet No More,” which aren’t real essay titles but could have been, also like “How Google Broke My Heart” or “Farewell MySpace” or “Je Ne Regrette Rien, Friendster.” So this essay never got written.

I was also writing emails to former Facebook friends who had noticed that I was gone from their friend list and who were taking my disappearance personally, all because of what I hadn’t written about quitting Facebook — which I didn’t start writing, because I had to placate my friends. Really, it wasn’t because of you, it was because of the whole enterprise, I wrote, which had begun to throw salt on my misanthropy. I went no farther than that — I feared offending them if I wrote about how difficult it became to have peaceable face-to-face relationships with people who projected unlikeability online.

I did tweet the observation that Facebook isn’t going to pay you a pension or 401k for all the time you spent there, and quite a lot of people liked this. So that was one veiled thing I wrote about why I quit Facebook.

I didn’t write about the shock of finding out that the two dear sons of one of my Facebook “friends” had been tragically killed in an auto accident, not recently but two years ago. Somehow I had missed this fact, until an anniversary post by one of the grieving parents — the status update elliptical, scourged by grief — pointed me toward the incident. I do not know what I would have done or written if I had known before. I did not write anything to them now because I felt so ashamed of my ignorance amidst a wealth of things to click on and know about. A wealth of things that may not matter so much. It’s always been a world in which you can lose your children or your parents in an instant, but somehow I have made it this far without knowing that in my gut.

Instead of writing about any of this, once I was not on Facebook anymore, I found myself sending emails with some witty insights or photos of my baby, but it just wasn’t the same; a request for housing help for a friend via email got no responses. However, I was now talking a lot about quitting Facebook, and this for a time became the most interesting thing about me. Fueled by how interesting I now was, I wrote a draft of an essay about writing about why I quit Facebook, which was clever but did not contain any of the things I have already said I didn’t write about. Plus, as the editor pointed out, I didn’t actually explain why I had quit. I hadn’t written about feeling like Facebook was a job. Like I was running on a digital hamster wheel. But a wheel that someone else has rigged up. And a wheel that’s actually a turbine that’s generating electricity for somebody else. That’s how I felt, which is what I should have written.

I thought about how I didn’t want to write about why I quit, only about how great it feels to be free, because how often do you get to leave a job? Something along the lines of, you stand up at your desk, you un-pin the photo of your dog or loved one from the cubicle wall, and you walk right out the door, don’t take the elevator because it’s slower than the stairs, and you bid the thrumming hive adios. Leaving Facebook felt like that. The sun singing on your face like springtime. The birds all whistling your theme song.

In the standard Social Media Exile essay, one doesn’t mention or announce when one returns to blogging or Twitter. For each platform or network one leaves, there’s another one to return to. Sometimes they’re the same. So I’m going to close this piece by breaking that convention and mentioning how easy it turns out to be to reactivate Facebook. When you sign back in, all your stuff is there, as if you’d never left. It’s like coming back to your country after a month in a foreign land, and it makes one feel that the whole reason for leaving is to make the place seem strange again. Being away from Facebook was certainly that. But I had to come back. That’s where all the people are. I’ve got a book coming out, and I need to let my friends know. Anyway, you know where to find me and what to talk about when you do. I’ll have some cookies baked.

In an uncollected letter to TS Eliot, Pasternak explores their shared aesthetic in ambitiously faulty English. Eliot’s art, he writes, like his own, is “a casually broken off fragment of the density of being itself; of the hylomorphic matter of existence …” Pasternak became much more accessible in his later work.

The metaphysics of Yuichi Yokoyama

Yuichi Yokoyama’s first full-length graphic novel, Travel, tells the story of a journey, and ends with a destination. Over the course of its nearly 200 silent pages, readers watch the progress of a train’s riders through a series of stunning, occasionally futuristic landscapes, and are thereby implicated in the journey themselves. The book’s final few pages show the three passengers whose embarkation begins the story leaving the train and taking a quick walk to a sea shore, where the froth of crashing waves prohibits further movement, literally ending the comic in its tracks. It’s a bold statement about form: sequences of panels depict motion, and when the motion must stop so must the comic. Every comic is a journey, a movement through something to something, and as such the only logical end point is a cessation of that movement.

Yokoyama’s second graphic novel, the recently translated Garden, also follows the logic of motion from beginning to end, of journey to destination. But in this book Yokoyama complicates things: Garden also begins with a destination, and for over 300 pages readers are invited to wonder if the journey it depicts is the same utilitarian movement through space depicted in Travel, or an end unto itself.

Garden begins with a strong echo of Plato’s Allegory of the Cave. A handful of the artist’s humanoid, fashion-forward characters stand assembled before a guard wearing a mask printed with a pattern that encourages the eyes to unfocus, and are denied entrance to the garden that memories of Travel suggest they have come a long way to see. Luckily, there is a breach in the wall that sections off the garden from the outside world — an outside world, crucially, that we are never allowed to see. By the end of page one, the characters we follow for the entirety of the narrative are through the wall and into the garden.

Garden begins with a strong echo of Plato’s Allegory of the Cave. A handful of the artist’s humanoid, fashion-forward characters stand assembled before a guard wearing a mask printed with a pattern that encourages the eyes to unfocus, and are denied entrance to the garden that memories of Travel suggest they have come a long way to see. Luckily, there is a breach in the wall that sections off the garden from the outside world — an outside world, crucially, that we are never allowed to see. By the end of page one, the characters we follow for the entirety of the narrative are through the wall and into the garden.

We will not see them leave. For the rest of the book, the characters negotiate ever more complex and physically demanding man-made topographical features, frequently risking life and limb without a mention of the fact that they are doing so. The dialogue betrays no interiority whatsoever, with completely interchangeable voices alternating between describing the bizarre sights their owners are witnessing and speculating on their purposes and the methods of their creation. Yokoyama’s fanciful setup nails the basic absurdity of modern leisure: the most privileged among us — the ones with the lives we believe are ideal — “work” by staring at screens, and “recreate” by climbing mountains.

Garden is more than satire, however, and Yokoyama’s sights are set much higher than the follies of vacationing. The nature of the obstacles his band of wanderers encounter progresses slowly but surely over the course of the book. Waterfalls of simple rubber balls and fountains made of stacked bowls give way to planters made of automobiles and resting areas constructed from airplane parts. Soon the terrain is incorporating giant paper pyramids, a winding maze of irrigation channels that forces its occupants to literally get their feet wet, and motorized blocks of rock that ferry riders up grooves cut into the side of mountains.

Garden is more than satire, however, and Yokoyama’s sights are set much higher than the follies of vacationing. The nature of the obstacles his band of wanderers encounter progresses slowly but surely over the course of the book. Waterfalls of simple rubber balls and fountains made of stacked bowls give way to planters made of automobiles and resting areas constructed from airplane parts. Soon the terrain is incorporating giant paper pyramids, a winding maze of irrigation channels that forces its occupants to literally get their feet wet, and motorized blocks of rock that ferry riders up grooves cut into the side of mountains.

Sidelines at the marathon

Sure, one could pick any thoroughfare in the city, or devise your own 26-mile spin through New York, and note change. But the marathon’s route, year in and year out, draws runners from across the globe and declares, in its punishing and entertaining way, “This is New York.”

Consider this, then, a how-we-live-now guide, observed in tank top.

Mile 2

Following the graceful curve of the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge, runners practically coast into Bay Ridge, their introduction to Brooklyn.

For most of the 20th century, this was a tight-knit enclave of Scandinavians, Irish and Italians, drawn by work on ships. When Grete Waitz, the nine-time marathon winner from Norway, went whizzing through there, her country’s flags would be flapping, said Bob Carlsen, 72, a third-generation Norwegian who cheered her on.

A Miss Norway is still crowned every spring, and Nordic Delicacies sells tins of fish pudding on Third Avenue.

But in the 1970s, Norwegians had seven social clubs, Carlsen said; now there are two, and they share space. And attendance at the annual Norwegian parade, held in May, “seems to be more limited each year,” he said.

The Irish and the Italians are dwindling as well, as Bay Ridge over the last 15 or so years has experienced the turnover and tumult of ethnic change.

New faces belong to Russians and Asians, with a huge Muslim population, too. Women in purple and gold hijabs stroll down Fifth Avenue past the Islamic Society of Bay Ridge, a popular mosque that is the community’s spiritual heart.

Ziad Khaled, 48, a Muslim born in Lebanon, now owns Hookahnuts, a store that sells pistachios with its tobacco pipes. A window sign promises “alcohol-free perfume.”

Muslims are among the fastest-growing segment of new arrivals in New York. And while the aftermath of Sept. 11 produced all sorts of discomfort and unease — many Pakistanis, for instance, either chose or were forced to leave — the arrival of Muslims in the city continues unabated.

Khaled, a Muslim, still feels the sting of the post-9/11 anger and anxiety, and from people who say all who practice Islam are terrorists. He said, “I’m ashamed to say this, but we need a lot more education in this country about religion.”

But he is not going anywhere, as he and his fellow Muslims in New York continue what can no doubt feel like their own marathon toward acceptance.

Mile 8

Slightly less than a third of the way into the route, the marathon takes a sharp right onto Lafayette Avenue, and thus into the heart of perhaps one of the neighborhoods more representative of change in New York: Fort Greene, Brooklyn.

Its rebirth reflects some of the sweeping changes that have altered daily life in the city: reductions in crime, explosions in property values, and the development and deepening of the city’s cultural life outside Manhattan.

Those changes, of course, have also ignited in Fort Greene the kind of conversation taking place in many corners of the city — about the merits of gentrification, the complications of integration and the implications of aggressive policing.

The shifts, seismic or nuanced, good or controversial, are beyond dispute. Shaded blocks, like those along South Portland Avenue, boast antique row houses with inviting stoops. Intersections are anchored by stylish eateries like Olea Mediterranean Taverna at Adelphi Street. There is dance and art, concerts and readings.

Access to all that doesn’t come cheap; one-bedroom apartments fetch half a million dollars. Prices have also soared for basics. Back in the 1970s, Ralph’s, a corner market at South Portland, was a Budweiser station, for marathon watchers or runners looking to reload some carbs. Now, Ralph’s stocks River House beer for $18 a six-pack.

Mile 11

Williamsburg can seem timeless, and for decades runners entering it have mingled, mostly with mutual respect, with the neighborhood’s Hasidic Jews in their traditional attire.

The neighborhood today, just a little way up Bedford Avenue, is the authentic, if slightly overexposed, frontier of one of the more significant demographic developments in New York in the last decade or so — the influx of young people from places other than New York. They have poured into the Lower East Side and the South Bronx, Bushwick and Astoria, but Williamsburg is the de facto capital of the infusion.

Of course, the hipsters of Williamsburg can have a retro take on their own dress that might make the Hasidim smile.

On a recent evening, near North Seventh Street, a man in a floppy blazer held what looked like a lime-green banana to his ear, then began talking into it. It was a plastic telephone handset, the kind that graced most America homes through the Reagan era, though its cord was plugged into a digital device. Following him, a group of girls giggled in awe.

The surge of twenty-somethings here in the past 10 years — the area’s construction fences are tagged with literate squiggles like “the world is crazy but you don’t have to feel like that” — is evident with the arrival of each L train at North Seventh Street, and is at least responsible in some significant part for driving the average age of a New Yorker to 36.

Already, though, the adjoining neighborhood on the marathon’s route, Greenpoint, looks at Williamsburg and sniffs: too old.

Patrick Ferrell, 27, moved to Greenpoint from Greensboro, N.C. A record label employee with Buddy Holly glasses, Ferrell also plays bass for No Man, No Eyes, an “experimental rock band.”

Ferrell said he would never relocate to Williamsburg; too many aging poseurs, he said. “Way too many ‘rad dads’ floating around,” he said.

Mile 14

In a legacy-solidifying push, Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg’s administration has rezoned some 20 percent of the city, a vast relaxation of restrictions on the building of housing, housing and more housing, much of it awfully expensive.

Long Island City’s changed character and altered look are a testament to that rezoning and the rebuilding that has come as a consequence. Yes, there are still myriad taxi depots, used-car lots and garages. Not to mention that huge billboards, for department stores, orange juice and cellphones, catch the eyes of commuters on the Long Island Expressway below.

But people who ran the route in the ’70s no doubt do double takes these days. Developers have recently lined Jackson Avenue with angular condos. A complex known as Hunters View was built over an auto-parts store. One Vernon Jackson rose over a razed glue factory. And One Hunters Point, on Borden Avenue, stands in the footprint of a parking lot where children a couple of generations back played touch football.

Adding so much sizzle to a sleepy city corner has charmed some business owners like Sung Park, 52, a deli owner on Vernon since 1988.

In 2009, he decided the neighborhood had changed enough that he could move beyond selling soda and sandwiches. He opened a museum on 50th Avenue, formally known as Underpenny Antiques, where his collection of 19th-century cast-iron pot holders, some 200 of them, are on display. Oh, and you can buy an oil painting there, too.

“Years ago, you couldn’t tell cabdrivers ‘Long Island City,’ so we would tell them to go to the Midtown Tunnel tollgate,” he said. “But now they know where to go.”

Mile 16

Mention First Avenue to club-hoppers of a certain age, and a wave of nostalgia, not to mention a flashback or two, might overtake them.

Starting in the 1960s, and bumping and grinding until the 1980s, the area that radiates north of the Queensboro-Ed Koch Bridge, where marathon runners now enter Manhattan, was a trove of boisterous disco/restaurants that were so memorable that they still inspire Austin Powers-like reactions.

“This place was absolutely swinging, night after night,” said Anthony King, who in 1972 opened Finnegan’s Wake, at East 73rd Street, to join the party. Today, the stucco-sided restaurant and the comedy club Dangerfield’s, circa 1969, are the only surviving traces.

Times have buttoned up. From a staff of two bartenders and a bouncer, and a closing time of 4 a.m., King has just one bartender today and winds things down at 1 a.m., he said.

His more shimmering peers seem to have met rather dull ends, contributing to the contemporary sleepiness of this stretch today.

Adam’s Apple, at No. 1117 (“Come take a bite out of life,” a TV commercial urged), is a mattress store; Magique, which later became a Chippendale’s, at No. 1110, sells bath towels. About the only watering hole to morph into something similar is the original T.G.I. Friday’s, at No. 1152, now Baker Street.

The most marquee-level club was clearly Maxwell’s Plum, at No. 1885. From 1966 to 1988, its burgers-and-caviar menu drew an A-list of actors like Cary Grant, Warren Beatty and Arnold Schwarzenegger. It was torn down in the mid-1990s, and the site now has an orange-brick 12-story apartment building with a Duane Reade.

“At some point, the scene headed downtown,” King said, “definitely somewhere below 14th Street.”

Mile 22

Harlem: For a century, it might have been the American address most strongly identified with African-Americans, and as such it was one of the signature locations on the marathon’s map of New York.

Yet for many years, Harlem, the upper Manhattan neighborhood between the East and Hudson Rivers that marathoners traverse along Fifth Avenue, was also considered imperiled: Block after block of brownstones had concrete blocks for windows. And rubble-choked lots could have an apocalyptic look.

Today, both notions of Harlem — as a distinctly black piece of the New York puzzle or as a place afflicted with urban ills — no longer quite apply.

Many of the neighborhood’s black residents, having been priced out of their homes or after having made a surprising killing by selling them, have left in the last decade. Indeed, the population in the standard boundaries of Harlem no longer has a black majority. In 2008, for instance, black residents accounted for just 40 percent of the population from roughly 96th to 155th Streets, census data shows. Even in one of Harlem’s cores — west of Fifth, by Marcus Garvey Park — residents are 10 percent white.

Whether this black-white flip-flop signals an unwanted invasion or just a chance for old-timers to cash out is a question that is fervently hashed out over dinner at Sylvia’s, the Lenox Avenue mainstay, or Red Rooster, a popular upstart nightspot.

Some new white arrivals are just glad to clear up misconceptions.

“I never came up here before because I was told it was dangerous,” laughed Ron Van Lieu, 70, who has lived in lower parts of Manhattan since the 1960s and moved to Harlem two years ago. An acting teacher at Yale’s drama school, Van Lieu was out walking his dog, Ella.

Harlem, it turns out, has also lured one of the marathon’s founders — George Hirsch, 77, who in 2008 traded his home in Murray Hill for a condo on Central Park North.

For all the change, or perhaps because of it, Hirsch thinks the race is no less able to unify the city now than it did when he helped dream it up. In fact, two years ago, when he ran it for the last time, “the guy from my bodega came over to give me a shout,” he said. “That was really nice.”

Tokyo subway posters, 1976-1982

Three annoying train monsters (October 1982)

The three annoying train monsters shown in the poster are Nesshii (the sleeping monster), Asshii (the leg-crossing monster), and Shinbunshii (the newspaper-reading monster).

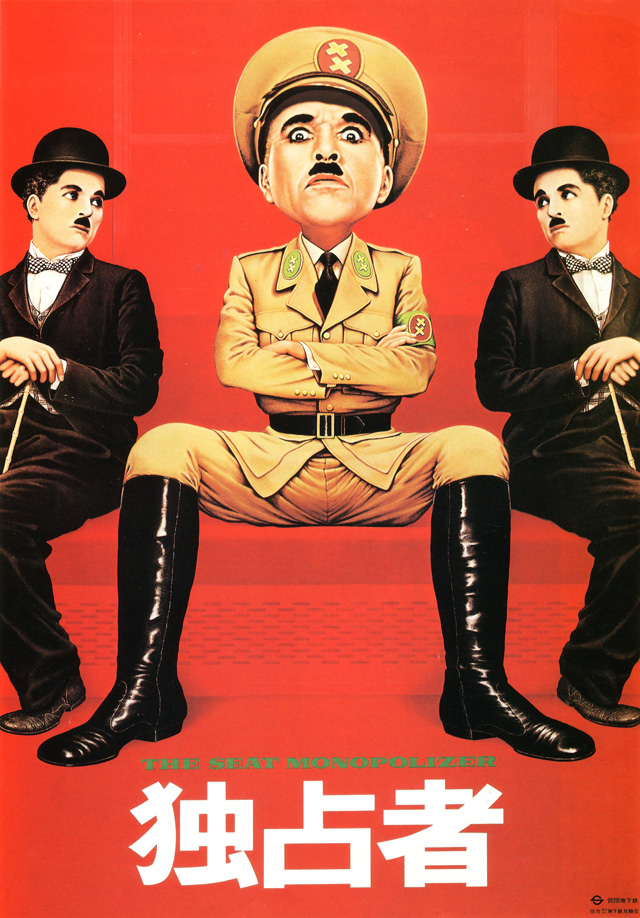

The Seat Monopolizer (July 1976)

Inspired by Charlie Chaplin’s “The Great Dictator,” this poster encourages passengers not to take up more seat space than necessary.

Don’t forget your umbrella (June 1977)

This poster of the high-class courtesan Agemaki (from the kabuki play “Sukeroku”), whose captivating beauty was said to make men forgetful, is meant to remind passengers to take their umbrellas when they leave the train.

Space Invader (March 1979)

This 1979 poster pays tribute to the extremely popular Space Invaders video arcade game and encourages passengers to read their newspapers without invading the space of other passengers.

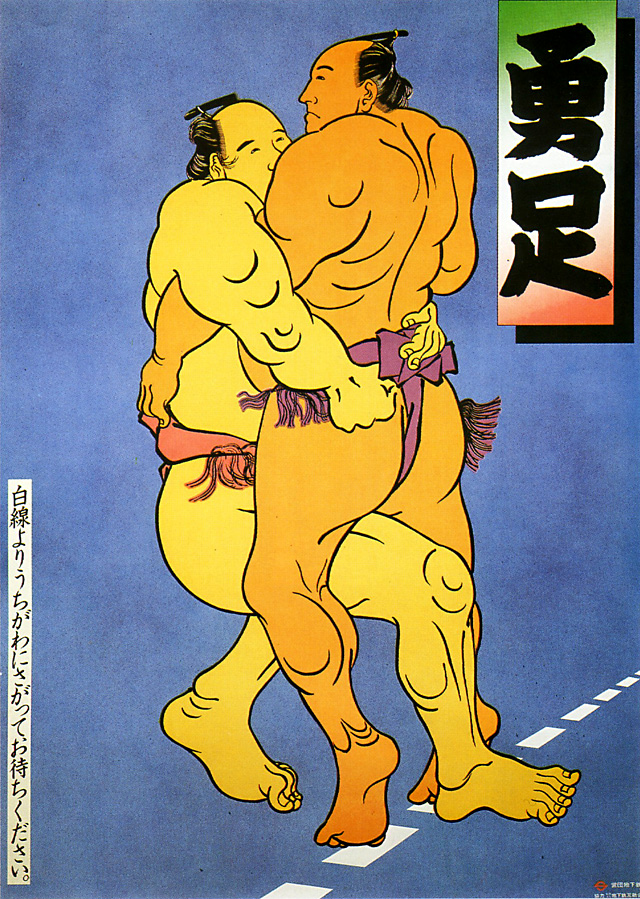

Isami-ashi: Wait behind the white line (May 1979)

The image of sumo wrestlers locked in combat serves as a reminder for passengers to stand safely behind the white line when waiting for the train.

Don’t forget your umbrella (October 1981)

The text at the top of this poster — which shows Jesus overwhelmed with umbrellas at the Last Supper — reads “Kasane-gasane no kami-danomi“ (lit. “Wishing to God again and again”). The poster makes a play on the words “kasa“ (umbrella) and “kasane-gasane“ (again and again).

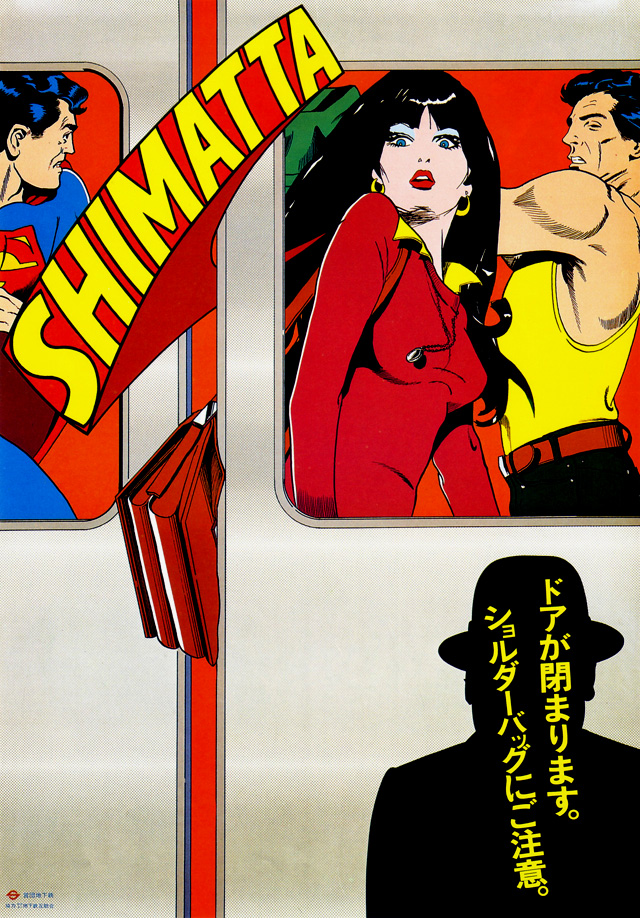

Shimatta (March 1977)

This poster warns passengers against getting their shoulder bags caught in the train doors.

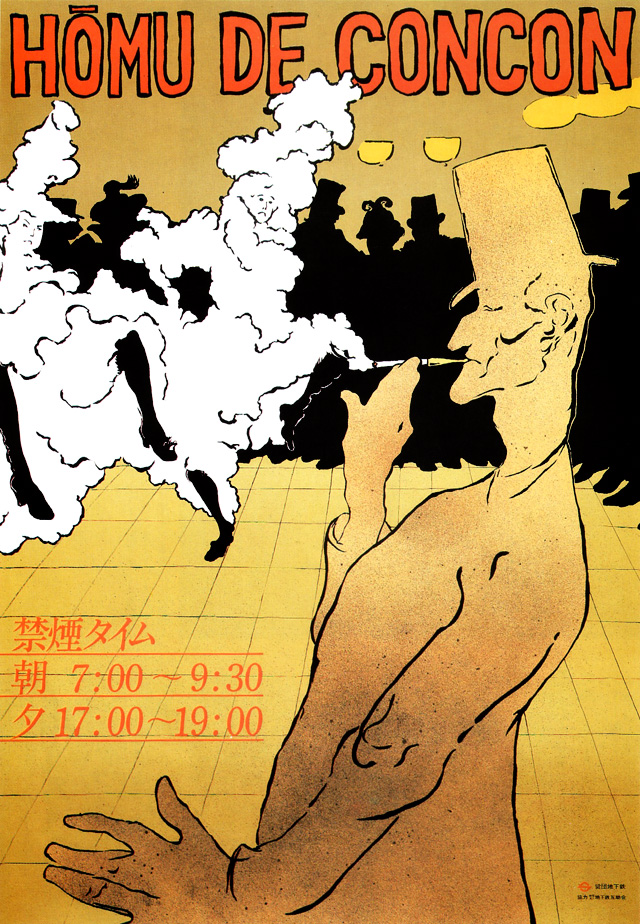

Coughing on the platform (January 1979)

Modeled after the paintings of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, this poster — titled “H_mu de Concon“ (coughing on the platform) — urges people not to smoke on the train platforms during the designated non-smoking hours (7:00-9:30 AM and 5:00-7:00 PM). The poster makes a play on the words “concon“ (coughing sound) and “cancan” (French chorus line dance).

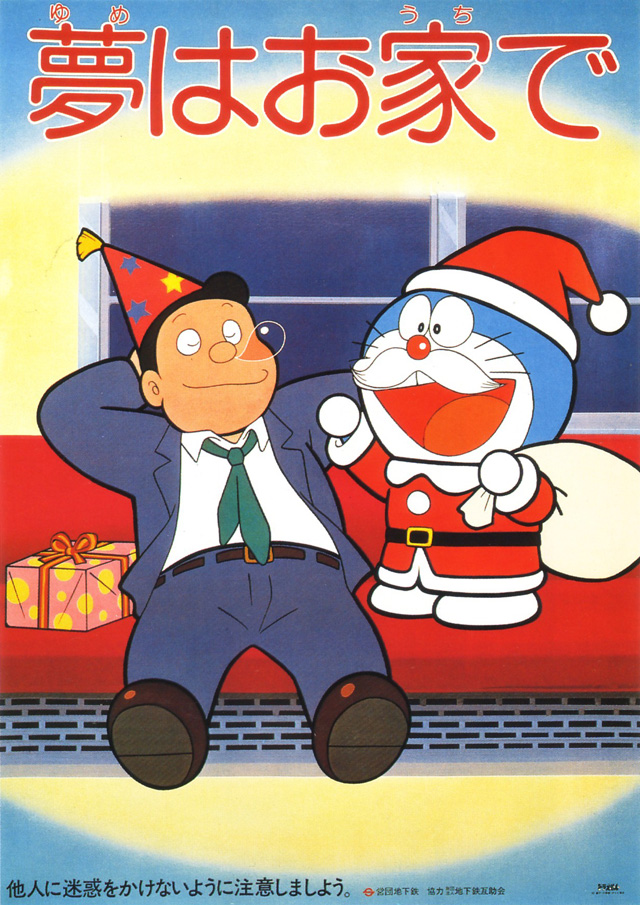

Dream at home (December 1981)

This poster, which features Doraemon dressed as Santa, encourages Christmas and end-of-year drunks not to pass out on the train.

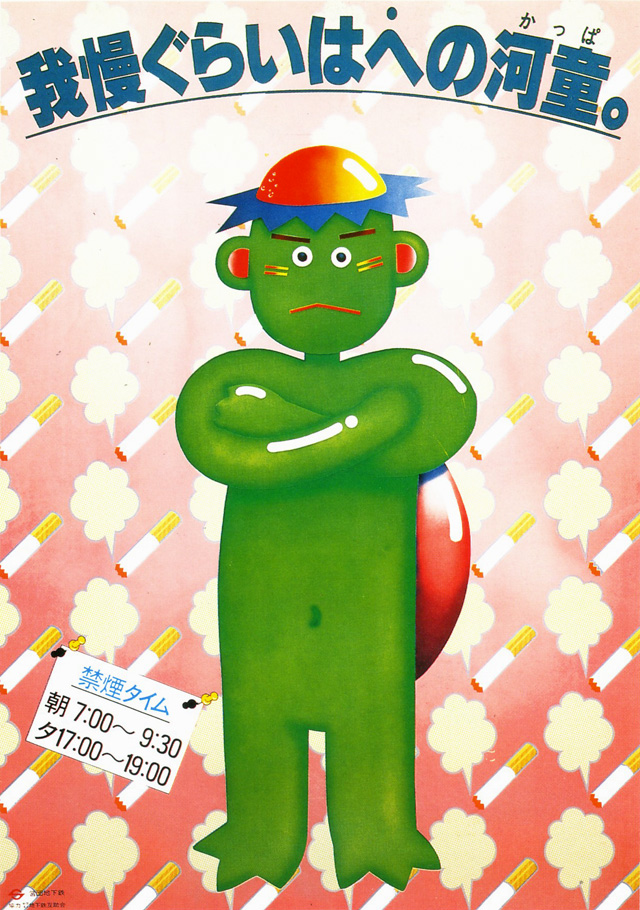

Kappa, (August 1979)

The image of a kappa (river imp) against a backdrop of lit cigarettes serves as a reminder not to smoke on the platform during the designated non-smoking hours (7:00-9:30 AM and 5:00-7:00 PM). The text at the top of the poster reads “Gaman gurai wa he no kappa,” which translates loosely as “waiting is no big deal.”

Umbrellas left behind in the subway (June 1976)

This Marilyn Monroe poster aims to remind passengers to take their umbrellas with them when they leave the train. The text in the top right corner — “Kaerazaru kasa“ (umbrella of no return) — is a play on “Kaerazaru Kawa,” the Japanese title for “River of No Return,” the 1954 movie starring Monroe.

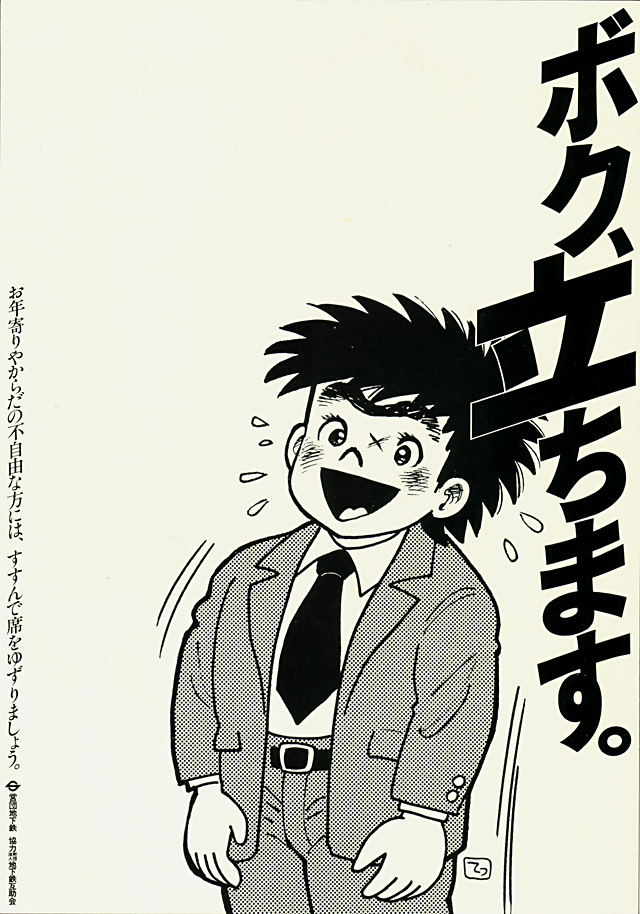

I’ll stand up (July 1979)

Uesugi Teppei, a character from the popular manga “Ore wa Teppei,” offers to give up his seat to the elderly and infirm.

Do not rush onto the train (April 1979)

This poster advises passengers not to rush onto the train at the last moment. The text (_______ is a play on the words ______ (kakekomi kinshi – “don’t rush onto the train”) and _____ (Kakekomi-dera – Kakekomi temple), which has long been known as a sanctuary for married women fleeing their husbands.

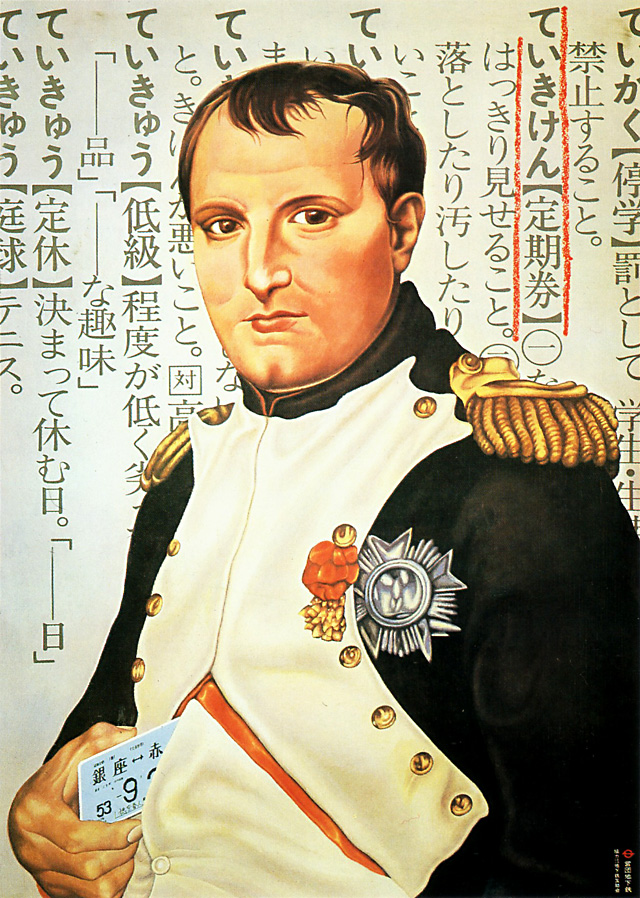

Clearly show your train pass (September 1978)

The image of Napoleon holding a partially concealed train pass is meant to remind passengers to clearly show their train passes to the station attendant when passing through the gates. The dictionary page in the background appears to be a reference to Napoleon’s famous quote, “The word ‘impossible’ is not in my dictionary.”

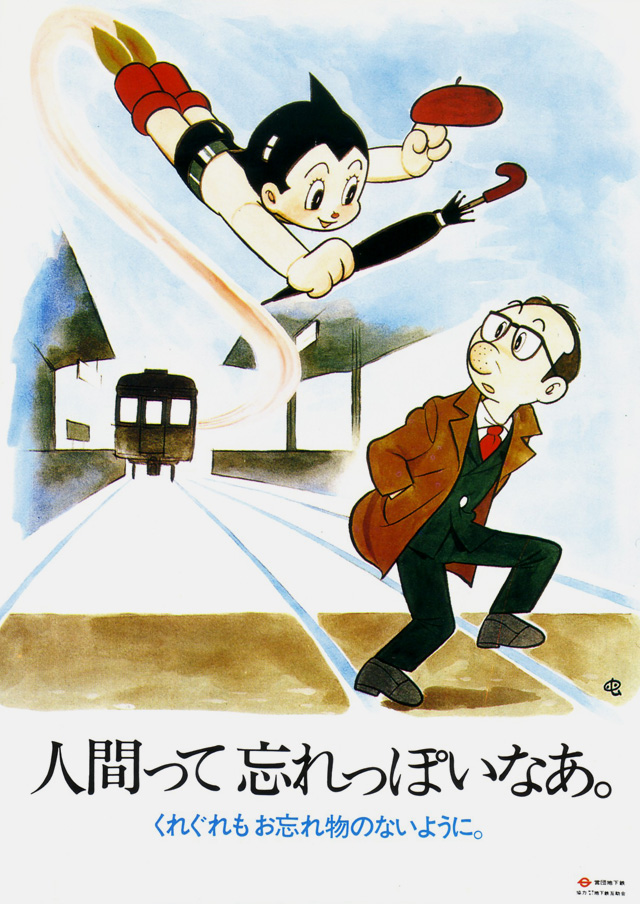

Humans are forgetful (February 1976)

This poster, which reminds passengers to take their belongings when they leave the train, shows Astro Boy returning a forgotten hat and umbrella to his creator, Osamu Tezuka.

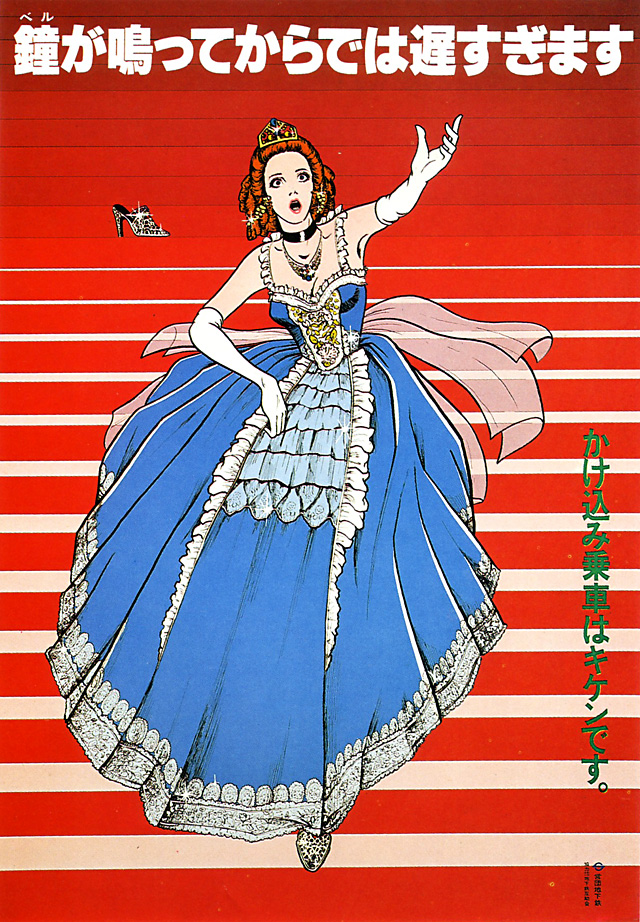

When the bell chimes, it’s too late (April 1977)

This poster, which depicts Cinderella rushing from the ball at the stroke of midnight, is meant to warn passengers against the danger of trying to rush into the train after the departure chime sounds.

Mary is tired (December 1977)

The image of Mary carrying baby Jesus aims to encourage passengers to give up their seats to mothers with small children.

You’ve had too much to drink (October 1976)

This October 1976 poster of a drinking Santa is addressed to the drunks on the train. The text, loosely translated, reads: “I look like Santa because you’ve had too much to drink. It’s only October. If you drink, be considerate of the other passengers.”

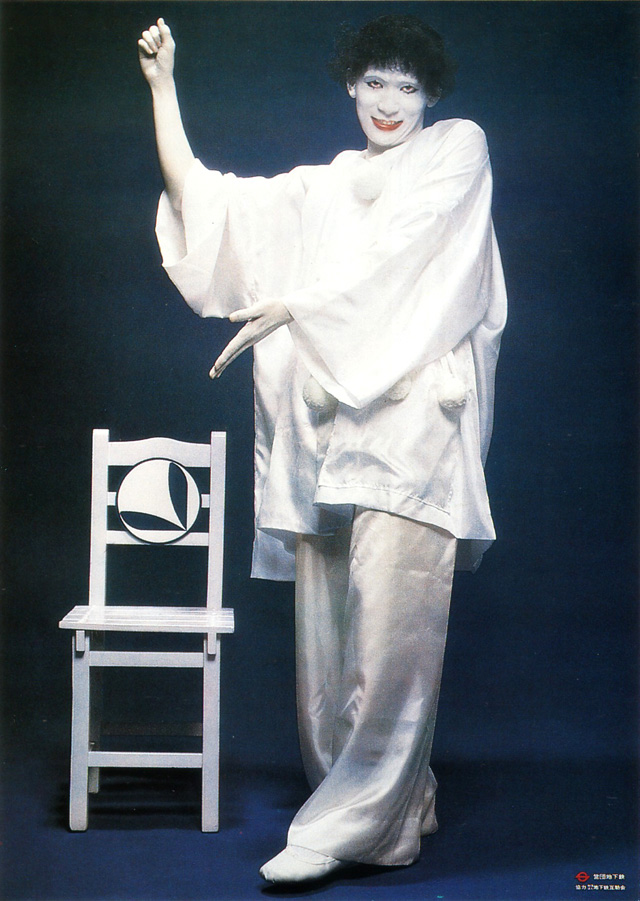

Marcel Marceau (October 1978)

Marcel Marceau gestures toward a priority seat reserved for elderly and handicapped passengers, expecting mothers, and passengers accompanying small children.

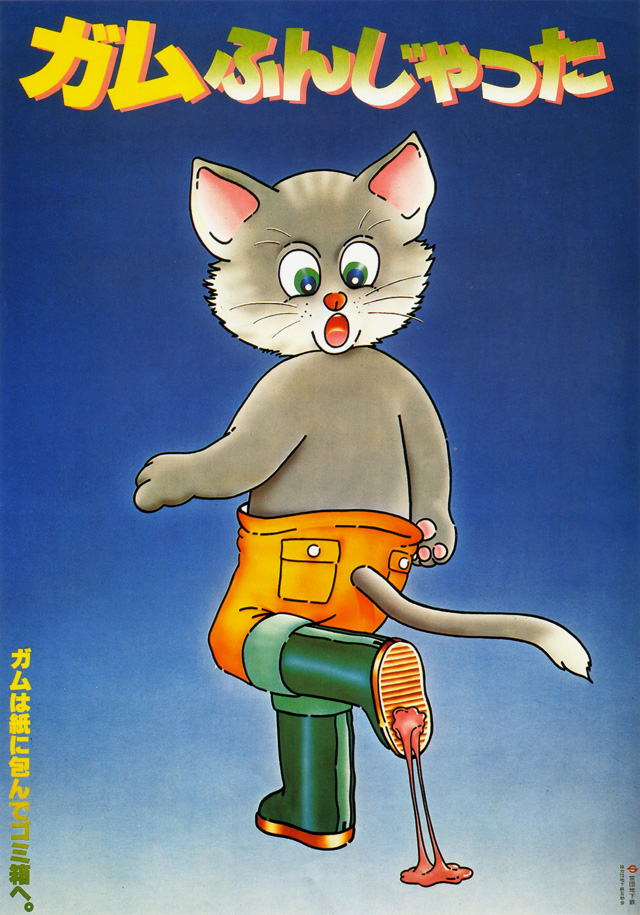

I stepped in gum (March 1980)

The image of a cat stepping in gum is a playful twist on the popular children’s song “Neko Funjatta“ (“I Stepped on a Cat”).

Non-smoking Time (November 1982)

The image of John Wayne on a mock cover of Time magazine serves as a reminder not to smoke on the platform during non-smoking hours (7:00-9:30 AM and 5:00-7:00 PM).

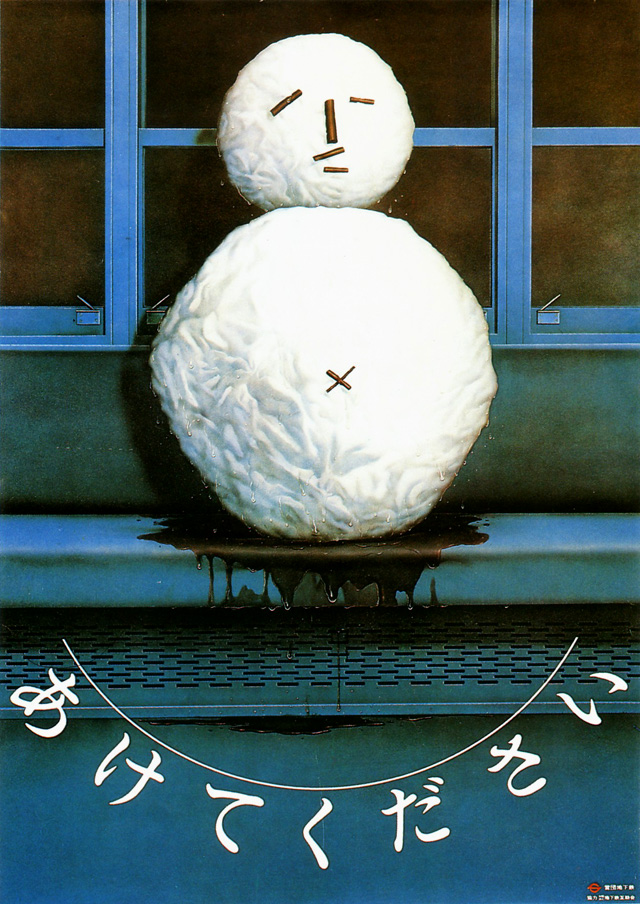

Please open it (July 1977)

This poster of a melting snowman aims to encourage passengers seated near a window to let cool air in when it is hot inside.

Christopher R. Beha on the 'realist novel'

… [David Foster] Wallace was the earliest and subtlest of his contemporaries in taking on the postmodern legacy. Nearly two decades ago he was writing in the Review of Contemporary Fiction about ‘irony, irreverence and rebellion’ and how they had ‘come to be not liberating but enfeebling in the culture today’s avant garde tries to write about’. He warned how useless these tools are ‘when it comes to constructing anything to replace’ what they have destroyed and didn’t believe the destruction itself could be undone. In the end, he took writers like Gaddis and Pynchon seriously, as Eugenides or Franzen refuse to do, and he couldn’t ignore their critiques of realism any more than he could ignore their shortcomings. The problem with realism, in Wallace’s view, was not that there was something naive about the desire to capture reality but that reality itself had changed in ways that realism couldn’t capture. Metafiction, he wrote, ‘was nothing more than a poignant hybrid of its theoretical foe, realism: if realism called it like it saw it, metafiction simply called it as it saw itself seeing itself see it.’

Wallace didn’t believe that this self-consciousness could be put back in its box or neutralised by the prelapsarian gestures of a book like The Marriage Plot, and sought to marry the formal mechanics and self-consciousness of postmodernism with the moral and emotional engagement of realism. To some, his humanised brand of post-postmodernism looked too much like the same old stuff, and many who might have been sympathetic to his aims were turned off by the results.

The Pale King, Wallace’s posthumous novel, suggests that he was struggling towards a synthesis of the warring elements in his work. Many took his death as a sign that the effort had defeated him. If you believed that the project of reconciling postmodern methods with the classical aims of the novel had destroyed Wallace, it would be a short step to seeing the entire undertaking as doomed. Eugenides’s depiction of Leonard Bankhead seems in part a refutation of this view. Leonard is smart, but he isn’t destined for groundbreaking work. His problems begin and end with the fact of his mental illness, but it isn’t a generational sickness: it’s all in his head.

During Wallace’s lifetime, Eugenides seems to have been among those who believed that he was part of the problem: ‘The moves people make today to seem antitraditional,’ Eugenides wrote, ‘are enervated in the extreme: the footnote thing, the author appearing in the book etc. I am yawning even thinking about them.’ The ‘footnote thing’ seems a particularly pointed allusion to Wallace. Wallace’s death may have caused Eugenides to reconsider. Near the end of The Marriage Plot, Mitchell has a conversation with Leonard in which he recognises him as a kindred soul, a spiritual seeker, rather than the cad he has taken him to be. But it’s too late: Leonard is already slipping away.

One has to admire the audaciousness of all this, even if it makes one uneasy. To borrow some terms from Semiotics 211, Eugenides has written a book that is at once ‘readerly’ and ‘writerly’, a book that never stops being a coming of age novel, that is forever winking through the mask but never lets it drop. He can’t be faulted for lack of ambition. He too is seeking a way forward rather than a mere retrenchment. The Marriage Plot doesn’t fail because it is ‘merely’ a realist novel, it fails because it is so often a pedestrian one. It makes every argument in favour of the tradition except the only one that matters.