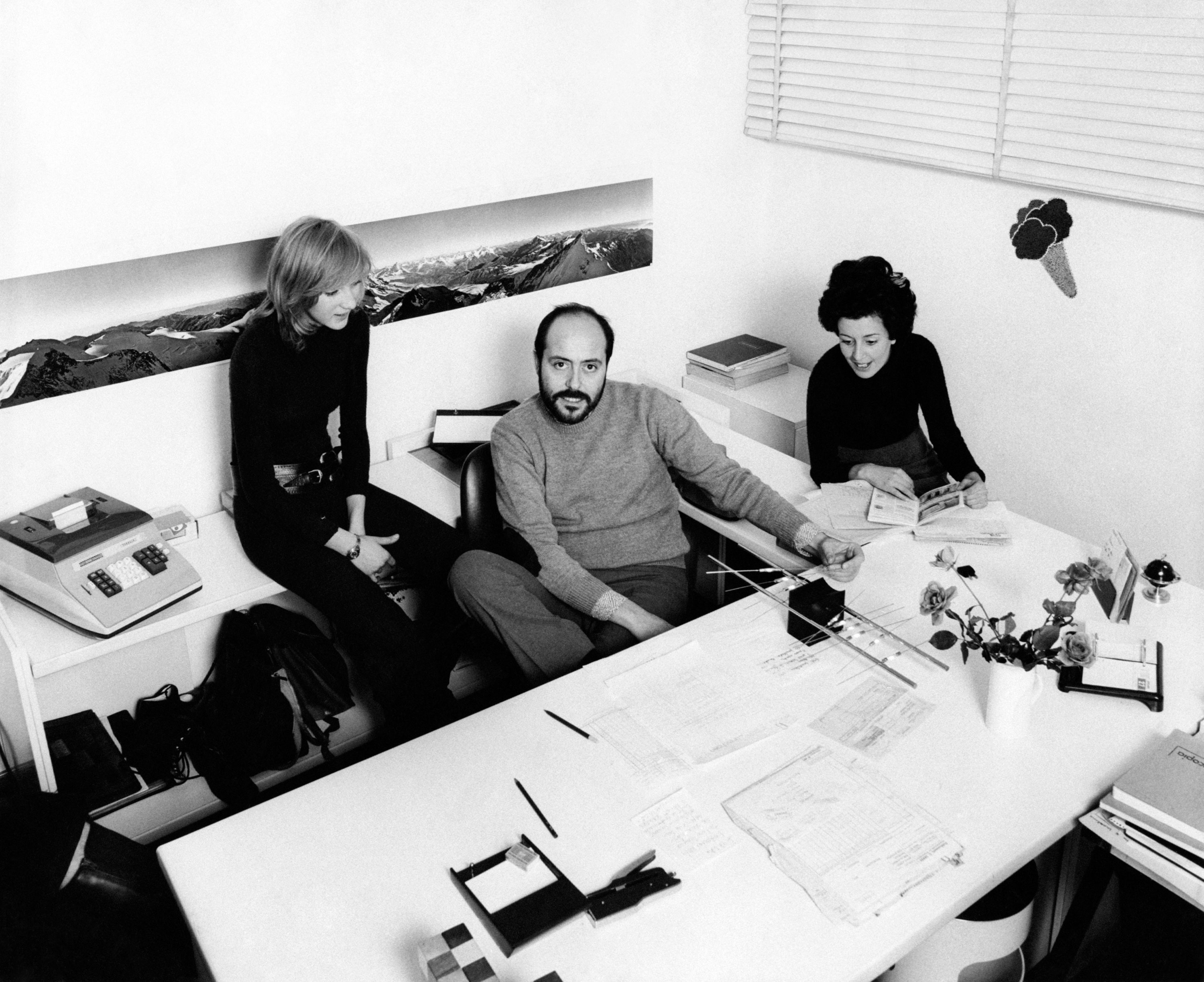

Elaine Lustig Cohen reflects on her career

My abstraction never came from narrative; it came from architecture. Even though I had many friends who were writers, I was never particularly drawn to narrative. When I finished my first paintings on view in the show, such as Centered Rhyme, I would look at them and there was always something more I wanted to explore, hence the repetition of shapes such as the diamond, the hexagon, and the parallelogram. There was a morphology to working in series like that. Part of my process did carry over to design, but none of my early design work was painted. Since in the early days of design we pasted up the images, they were manipulations of photographs, colors, and fonts. What did carry over to my paintings from the graphic work was in the sketching, because to do anything that hard-edged I had to do a sketch when I planned the paintings.

For me, painting is a combination of the flat plane and the color. When I sit and look at things, it is always about the interaction of the planes. When I was doing graphic design in the postwar period, architecture was going to save the world! We were all going to be good in life because of the space we lived it in. It’s a wonderful dream, but that was the mind-set of the time. On Alvin Lustig’s shelf, when I married him, were books by Piet Mondrian, Sigfried Giedion, László Moholy-Nagy, and Lewis Mumford. Postwar expression for me was not about individualism or the freedom of a Jackson Pollock; it was about cultural renewal in an architectonic expression.

Architecture was always a part of my informal training as an artist. When Alvin and I lived in Los Angeles, we did not go to museums. There were no museums there in those days, but during 1948 and 1949, Arts & Architecture magazine commissioned young architects to design the Case Study Houses in Los Angeles. We spent our weekends driving around and looking at Richard Neutra and Rudolf Schindler. That was the entertainment. We were friends with the Eameses; Alvin knew the Arensbergs, and we would go to their home to view art. From the very beginning, art for me was about this interplay with architecture.

My solo design career lasted from around 1957 to the mid-1960s, which is a short history compared with how long I have been painting, but it all started when Philip Johnson called me and said, “Get on with it! Do it.” He had hired Alvin to do the signage for the Seagram Building, but when Alvin died he had not designed anything yet. Two weeks or so later, I got the call that would lead to ongoing collaborations with Philip. I had never designed anything on my own in my life, but I did every piece: the 375 address outside, the Brasserie sign, firehose connections, switches, even things that wouldn’t be seen. It helped me survive for three years. I did all the catalogues for every museum he designed, every piece that had lettering on it. Philip was very fast and always had three ideas for every one idea you showed him, but if I stuck to my guns he would always go with my instincts.

When I started having people over to my studio, they were mainly writers—Donald Barthelme, Ralph Ellison, and John Ashbery—but there were artists too, such as Helen Frankenthaler and Robert Motherwell. Everyone was supportive, but I was still an outsider. That is the way history is written. I am still interested in painting, typography, collage, watercolor, and the computer; I still do everything. There is no line for me. You are lucky to be creative and be able to do it.

—As told to Andrianna Campbell

J. Irwin Miller, Illustrated furniture inventory, ca. 1958, FF 78, Miller House and Garden Collection, IMA Archives, Indianapolis Museum of Art, Indianapolis, Indiana. (MHG_IIIc_FF078_009)

Adam Gopnik on food writing, 2005

[Bernard] Loiseau suffered throughout his life from a too-late-identified bipolar disorder, a syndrome that ought to be known by its old French name, folie circulaire. It’s a syndrome that can strike truck drivers and Zen monks as easily as cooks, so any general principles should be taken with caution. Still, Loiseau, if not typical, is in many ways exemplary of the chef’s dilemma.

He was a member of perhaps the last generation of artists who were true to an ideal and a practice that had begun in the nineteenth century. He learned to cook as an intern in the kitchen of the Frères Troisgros, near Lyon, where he mastered the terrifying discipline by chopping onions and filleting fish for twelve hours a day; he even learned to kill frogs by slapping their heads casually against the kitchen table. The Troisgros kitchen opened every door in those days, and in the early seventies Loiseau, with almost no other apprenticeship, made a name for himself, doing simple country cooking at a glorified bistro just outside Paris. He was financed by a shrewd promoter named Claude Verger, who saw that elemental food could be popular and still presented to the critics as something new: a variant of the new cooking, or nouvelle cuisine.

That it was simple and not genuinely new does not mean that it was without value; no one had been cooking that way with passion or conviction for a while. Calling plain cooking high cooking was in itself a radical act. Loiseau became a star, and, with money advanced by Verger, he bought La Côte d’Or, a famous old restaurant in the Burgundy town of Saulieu. In the dense, deep-eating days of gratins and casseroles, the place had held three stars in the Michelin Red Guide; by sheer effort, Loiseau built it back up, and the reader cheers with him when he finally gets his three stars, in 1991.

The trouble was that there was no reason to go to Saulieu except to eat, and this made Loiseau particularly, even uniquely, vulnerable to the Guide and its system of stars and inspectors. The Guide no longer had an easy or organic relation to French cooking. The Red Guide grew up with the automobile, and with the idea of the long journey away from Paris that required several stops for lunches and dinners. By the nineteen-eighties, though, the new autoroutes and the high-speed trains (and the planes, racing over) had reduced the need for road stops. The Michelin inspectors, gloomy middle-aged men eating alone, used to be indistinguishable from the other gloomy middle-aged men eating alone, and their stars were a kind of summary of the opinions of all those tired travelling professionals. Now all that’s left of this once self-evident system is the inspectors, dining alone and passing out stars. People do not drive by the restaurant and stop to eat; they drive to the restaurant and stop for a three-star meal. To be a destination is a difficult trade: it is nice to run a place where the food, in the famous phrase, is worth a journey, hard to keep it going when the only reason anyone makes the journey is to eat the food.

Loiseau was terrified of losing his stars, particularly when François Simon, of Le Figaro, hinted that La Côte d’Or was on its way down. The chef may have been paranoid in this, but he was hardly alone. All artists in all fields despise all critics all the time. (They may like the individual critic, but they despise his conviction that he has a right to criticize.) Still, there are levels of loathing, as there are circles in Hell. Writers at least recognize that the critic is a writer, and shares a table, if not an agent. Magicians, on the extreme edge, despair of those outside their circle ever knowing the difference between a trick that anyone can buy for six dollars and sleight of hand that only two people have learned in six years. Chefs are close to magicians in their certainty that their critics cannot tell the difference between something that takes time, thought, and talent and something that dazzles only by surprise, perversity, and snob appeal. But, even more than magicians, chefs depend on the good opinion of those whose opinions they cannot think are worth having—and the nature of Loiseau’s cooking left him open to the exhaustion of critics.

Chelminski points out that food critics are even more inclined than other kinds to fatigue. Most food critics are sick of eating rich, expensive food and will do almost anything to have something new; a perfectly prepared veal chop (one of Loiseau’s elemental specialties) first gets a smile, and then a yawn. But Loiseau, his biographer admits, was at an edge of simplicity so extreme that it hinted at innocence. (Chelminski suggests that Loiseau’s training was short on fundamentals; he was notorious among his staff for being unable to make even basic sauces.) Famous for the purity of his approach, Loiseau deglazed his pans with water instead of wine or even stock. It was admirably minimal, but it also tended to be oddly ascetic and depressing; the elemental and the elegant are sisters, but not twins. Loiseau had no hesitation about publishing a recipe for John Dory served with a purée made of boiled celery. (It seems so simple that one is convinced that it must be mysteriously great; I have made it, and it tastes like fish with boiled celery purée.)

Feghoot

A story pun (also known as a poetic story joke or Feghoot) is a humorous short story or vignette ending in a pun (typically a play on a well-known phrase) where the story contains sufficient context to recognize the punning humor.[1] It can be considered a type of shaggy dog story. This storytelling model apparently originated in a long-running series of short science fiction pieces that appeared under the collective title “Through Time and Space with Ferdinand Feghoot”, published in various magazines over several decades, written by Reginald Bretnor under the anagrammatic pseudonym of ‘Grendel Briarton’. The usual formulae the stories followed were for the title character to solve a problem bedeviling some manner of being or extricate himself from a dangerous situation. The events could take place all over the galaxy and in various historical or future periods on Earth and elsewhere. In his adventures, Feghoot worked for the Society for the Aesthetic Re-Arrangement of History and traveled via a device that had no name but was typographically represented as the “)(”. The pieces were usually vignettes only a few paragraphs long, and always ended with a deliberately terrible pun that was often based on a well-known title or catch-phrase.

“Through Time and Space with Ferdinand Feghoot” was originally published in the magazine Fantasy and Science Fiction from 1956 to 1973. (In 1973, the magazine ran a contest soliciting readers’ Feghoots as entries.) The series also appeared in Fantasy and Science Fiction‘s sister magazine Venture Science Fiction Magazine, and later in Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine, Amazing Stories, and other publications. The individual pieces were identified by Roman numerals rather than titles. The stories have been collected in several editions, each an expanded version of the previous, the most recent being The Collected Feghoot from Pulphouse Publishing.

Many of the ideas and puns for Bretnor’s stories were contributed by others, including F. M. Busby and E. Nelson Bridwell. Other authors have published Feghoots written on their own, including Isaac Asimov (who wrote a story that ended “A niche in time saves Stein”) and John Brunner. There have been numerous fan-produced stories as well.

The name Feghoot and the nature of the stories—detailed and tedious, yet ending in vaguely familiar catchphrases—may have been inspired by Walter Bagehot, a major literary and political figure from the late 1800s.

Tsumori Chisato F/W 2014-15

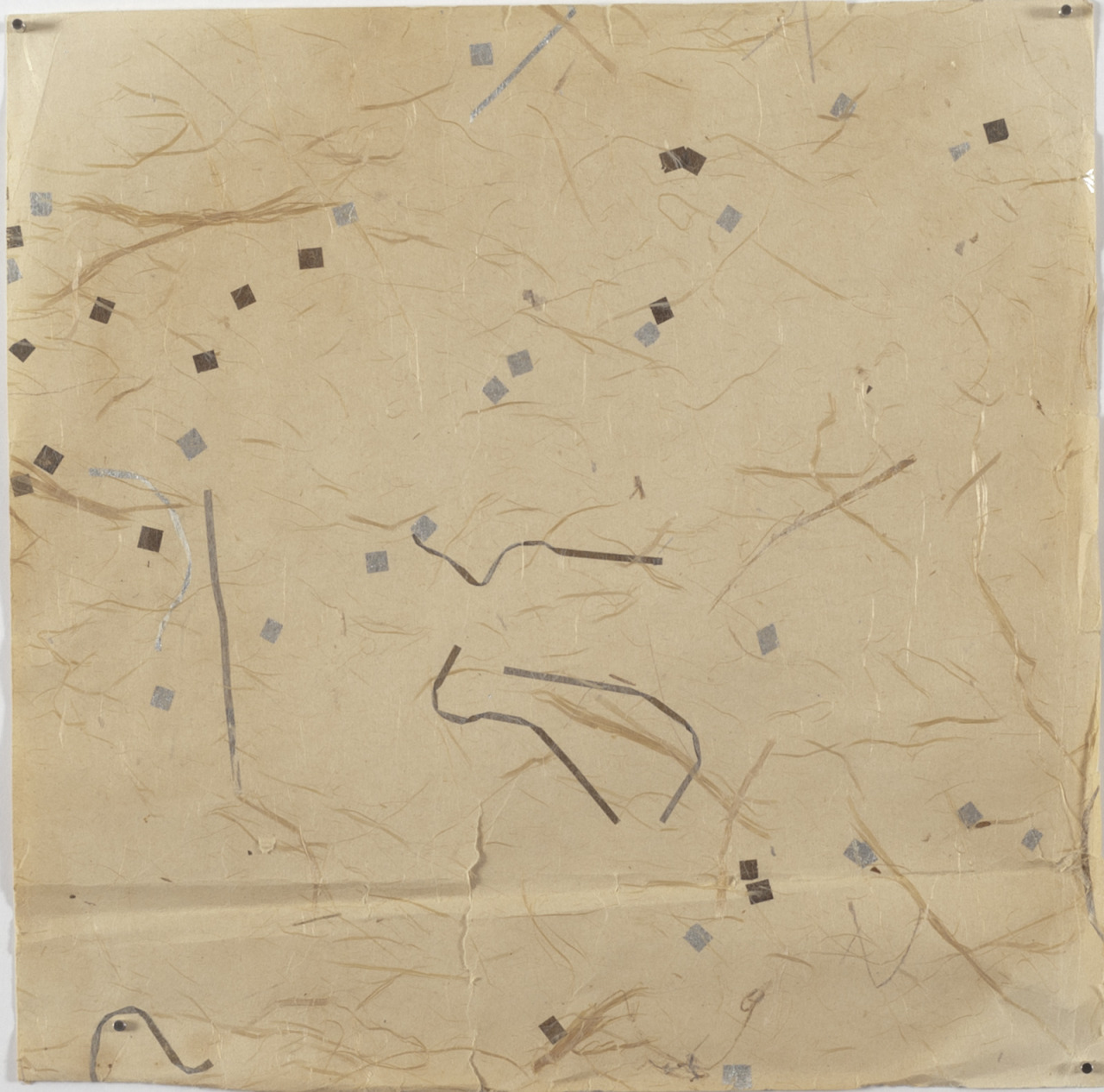

Kin Gin wallpaper sample “K-225”, for Guest Bathroom, 1978, Box 88, Folder 25, Miller House and Garden Collection, IMA Archives, Indianapolis Museum of Art, Indianapolis, IN. (MHG_IVa_B088_F025_001, 003)

You are the rainbow

Manzotti is what they call a radical externalist: for him consciousness is not safely confined within a brain whose neurons select and store information received from a separate world, appropriating, segmenting, and manipulating various forms of input. Instead, he offers a model he calls Spread Mind: consciousness is a process shared between various otherwise distinct processes which, for convenience’s sake we have separated out and stabilized in the words subject and object. Language, or at least our modern language, thus encourages a false account of experience.

His favorite example is the rainbow. For the rainbow experience to happen we need sunshine, raindrops, and a spectator. It is not that the sun and the raindrops cease to exist if there is no one there to see them. Manzotti is not a Bishop Berkeley. But unless someone is present at a particular point no colored arch can appear. The rainbow is hence a process requiring various elements, one of which happens to be an instrument of sense perception. It doesn’t exist whole and separate in the world nor does it exist as an acquired image in the head separated from what is perceived (the view held by the “internalists” who account for the majority of neuroscientists); rather, consciousness is spread between sunlight, raindrops, and visual cortex, creating a unique, transitory new whole, the rainbow experience. Or again: the viewer doesn’t see the world; he is part of a world process.

Max Factor’s Kissing Machine, c. 1939