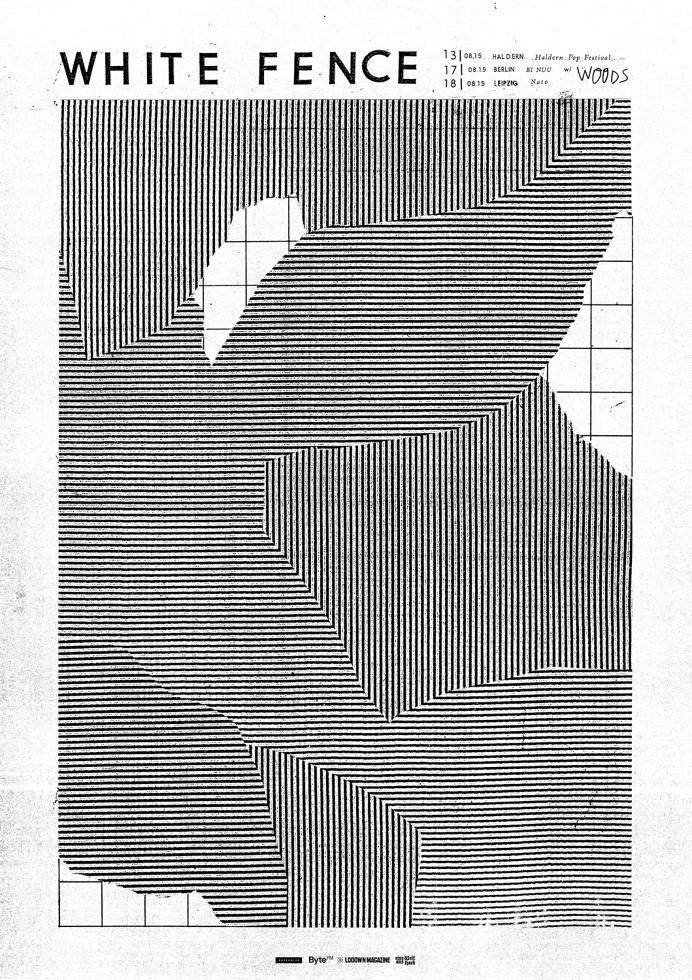

Lucy Lippard’s inventory of conceits in post-Pollock, New York art. From the catalog for “New York 13,” Vancouver Art Gallery, winter 1969.

Some customers pour beer into clear McCafé plastic cups and drink it right in the open. A man called Shamrock swills straight vodka from a Dasani water bottle at a table near the entrance. The other day, a man headed straight for the bathroom, pausing only to open his backpack and grab a bag of heroin, known as “dog food.” Another day, a couple shared a McDonald’s vanilla shake at a side table and swallowed “sticks,” the anti-anxiety prescription drug Xanax, and “pins,” the anti-anxiety pill Klonopin. On a recent Wednesday, an ambulance showed up to carry away a regular who had been stabbed in an adjacent doorway, leaving blood all over the sidewalk.

Other types of regulars, the so-called normals, frequent this McDonald’s, like the TV newsman in a suit who goes there only because it is near the office. And the nun of 70 years who sometimes sits in the back, where she likes to watch the scene unfold like a Broadway show.

“I get an ice cream cone for a dollar,” said the nun, Elaine Goodell, 89, who lives in a nearby convent and works as a hospital chaplain. “Then I will usually buy a medium French fries. I love the salt and the sweet. And that’s what you get here too — the salt and sweet of humanity.”

Flowing locks

On first approach to a novel, Nabokov claimed, we are overwhelmed with too much information and fatigued by the effort of scanning the lines. Only later, on successive encounters with the text, will we begin to see and appreciate it as a whole, as we do with a painting. So, paradoxically, then, “there is no reading, only rereading.”

This attitude, I recently suggested in this space, amounts to an elitist agenda, an unhappy obsession with control, a desire to possess the text (with always the implication that there very few texts worth possessing) rather than accept the contingency of each reading moment by moment.

“Wrong!” a reader objects. “Isn’t it true,” he invites an analogy with music “that the first time we hear a new song we can’t really enjoy it? Only after two or three hearings will it really begin to give us pleasure.” He then adds this intriguing formulation:

When we perceive something new for the first time we cannot really perceive it because we lack the appropriate structure that allows us to perceive it. Our brain is like a lock maker that makes a lock whenever a key is deemed interesting enough. But when a key—for example, a new poem, or a new species of animal—is first met, there is no lock yet ready for such a key. Or to be precise, the key is not even a key since it does not open anything yet. It is a potential key. However, the encounter between the brain and this potential key triggers the making of a lock. The next time we meet or perceive the object/key it will open the lock prepared for it in the brain.

It’s an elaborate theory and in fact the reader turns out to be the philosopher and psychologist Riccardo Manzotti. Intriguing above all is the reversal of the usual key/lock analogy. The mind is not devising a key to decipher the text, it is disposing itself in such a way as to allow the text to become a key that unlocks sensation and “meaning” in the mind.

Is Manzotti right? And if so, what does it tell us about reading?

Certainly we have all had the experience he describes on first encounter with difficult texts, poetry in particular. My first reading of The Waste Land, in a high-school literature class at age sixteen, was hardly a reading at all. It would take many lessons and cribs and further readings before suddenly Eliot’s approach could begin to awaken recognition and appreciation, before “April is the cruellest month,” that is, genuinely reminded me how difficult life and change could be in contrast to hibernation. The mind had conjured a lock that allowed the poem to function as a key; it fitted into my mind and something turned and swung open.

Two reflections. This Waste Land lock also seemed well suited to or easily adapted for a range of other keys. My mind could now be opened by other modernist poems far more quickly. Eliot’s other poems, in particular, all activated the senses smoothly enough. And while one would never perhaps reach the point of satisfying all one’s curiosity for a new poem in a single reading, still the lock-making process was now infinitely faster, to the point that there would sometimes be a sense of déjà vu: Oh, it’s this sort of lock the key wants to open. Or even: Oh not this again, how disappointing! Which perhaps explained why poets now no longer wrote in this way and had moved on.

This prompts a second reflection. With a certain kind of reading the pleasure lies in the lock-making process, the progressive meshing of mind and text. Once we are familiar with the kind of experience the text opens up in our minds, we will be less excited. Or at least, the pleasure will be of a different kind, offering the reassurance of the known, or simply a happy reminder of that more strenuous lock-making period. Such a distinction might help us tackle the old chestnut of the difference between genre fiction and literary work. There is no continuing learning process with genre fiction. We know how to read a Maigret and would never dream of rereading one. It always prompts the same reactions. But with a literary novel, we would expect the pleasure of an effort of adjustment, of new vistas being opened in the mind.

So Nabokov was right perhaps, or at least for complex novels, which for him were probably the only ones he was interested in. We have to reread.

Portrait of the artist as a dormant snail

A certain famous historical desert snail was brought from Egypt to England as a conchological specimen in the year 1846. This particular mollusk (the only one of his race, probably, who ever attained to individual distinction), at the time of his arrival in London, was really alive and vigorous; but as the authorities of the British Museum, to whose tender care he was consigned, were ignorant of this important fact in his economy, he was gummed, mouth downward, on to a piece of cardboard, and duly labelled and dated with scientific accuracy, ‘Helix desertorum, March 25, 1846.’ Being a snail of a retiring and contented disposition, however, accustomed to long droughts and corresponding naps in his native sand-wastes, our mollusk thereupon simply curled himself up into the topmost recesses of his own whorls, and went placidly to sleep in perfect contentment for an unlimited period. Every conchologist takes it for granted, of course, that the shells which he receives from foreign parts have had their inhabitants properly boiled and extracted before being exported; for it is only the mere outer shell or skeleton of the animal that we preserve in our cabinets, leaving the actual flesh and muscles of the creature himself to wither unobserved upon its native shores. At the British Museum the desert snail might have snoozed away his inglorious existence unsuspected, but for a happy accident which attracted public attention to his remarkable case in a most extraordinary manner. On March 7, 1850, nearly four years later, it was casually observed that the card on which he reposed was slightly discoloured; and this discovery led to the suspicion that perhaps a living animal might be temporarily immured within that papery tomb. The Museum authorities accordingly ordered our friend a warm bath (who shall say hereafter that science is unfeeling!), upon which the grateful snail, waking up at the touch of the familiar moisture, put his head cautiously out of his shell, walked up to the top of the basin, and began to take a cursory survey of British institutions with his four eye-bearing tentacles. So strange a recovery from a long torpid condition, only equalled by that of the Seven Sleepers of Ephesus, deserved an exceptional amount of scientific recognition. The desert snail at once awoke and found himself famous. Nay, he actually sat for his portrait to an eminent zoological artist, Mr. [A.N.] Waterhouse; and a woodcut from the sketch thus procured, with a history of his life and adventures, may be found even unto this day in Dr. [S.P.] Woodward’s ‘Manual of the Mollusca,’ to witness if I lie.

“From childhood, he was very strong,” his father, Miguel Valerio Colon, recalled. “He was capable of pulping up to 1,000 crates of coffee beans in a day.”

Sometimes, while transporting bags of beans for his father’s produce business, young Bartolo would park his pet donkey, Pancho, beside a sloping lot that served as a baseball field and play a few innings with other children, using balls made of cloth.

“The only way you would be able to play was to escape from my dad,” Colon said, “because the main thing was working.”

If the de-pulping machine built up his arms, then throwing rocks to knock fruit from trees developed his accuracy. “Throwing at coconuts and mangoes,” Colon said. “But the coconut was the most difficult.”

From Thomas Mann, The Magic Mountain (1924):

It would have been difficult to guess his age, but it surely had to be somewhere between thirty and forty, because, although the general impression was youthful, he was already silvering at the temples and his hair was thinning noticeably, receding toward the part in two wide arcs, making the brow even higher. His outfit—loose trousers in a pastel yellow check and a wide-lapelled, double-breasted coat that was made of something like petersham and hung much too long—was far from laying any claim to elegance. The edges of his rounded collar were rough from frequent laundering, his black tie was threadbare, and he apparently didn’t even bother with cuffs—Hans Castorp could tell from the limp way the coat sleeves draped around his wrists. All the same, he could definitely see that he had a gentleman before him—the refined expression on the stranger’s face, his easy, even handsome pose left no doubt of that. This mixture of shabbiness and charm, plus the black eyes and a handlebar moustache, immediately reminded Hans Castorp of certain foreign musicians who would appear in his hometown at Christmastime and strike up a tune, then gaze up with velvet eyes and hold out their slouch hats to catch the coins you threw them from the window.

The debtor made a contract with the creditor and pledged that if he should fail to repay he would substitute something else that he “possessed,” something he had control over; for example, his body, his wife, his freedom…

Let us be clear as to the logic of this form of compensation: it is strange enough. An equivalence is provided by the creditor’s receiving, in place of a literal compensation for an injury (thus in place of money, land, possessions of any kind), a recompense in the form of a kind of pleasure—the pleasure of being allowed to vent his power freely upon one who is powerless, the voluptuous pleasure “de faire le mal pour le plaisir de le faire [of doing evil for the pleasure of doing it],” the enjoyment of violation….In “punishing” the debtor, the creditor participates in a right of the masters….The compensation, then, consists in a warrant for and title to cruelty.

‘Henry does resemble me,’ Berryman told an interviewer, ‘and I resemble Henry; but on the other hand I am not Henry. You know, I pay income tax. Henry pays no income tax. And bats come over and stall in my hair – and fuck them, I’m not Henry; Henry doesn’t have any bats.’