What's with all the fucking bunnies?

“A dearth of sweeping theories about the differences between the sexes will be found in the pages ahead,” promises critic Laura Kipnis in her latest book, Men. In place of theories, she assembles divergent examples of the form, a data set designed to flummox even the most determined essentializer. Here we encounter porn mogul Larry Flynt, queer theorist and poet Wayne Koestenbaum, and Straussian philosopher of manliness Harvey Mansfield. Appearances are made by quondam presidential candidate John Edwards, pugnacious author-critic Dale Peck, and a Marxist professor who, upon being denied sex by the author, pronounces Kipnis incurably “bourgeois.” (Idiosyncratic examples aside, women reading this book will do a fair amount of I-know-the-type head-nodding.) “I met Hustler magazine’s obstreperous redneck publisher Larry Flynt twice,” writes Kipnis, “the first time before he started believing all the hype about himself and the second time after.” Tasked with writing about the paraplegic pornographer, Kipnis had been collecting back issues of Hustler “the way some people collect Fiesta ware.”

For the uninitiated, Hustler is not the gauzy dreamworld of Playboy but a magazine given to photo spreads of amputees and hermaphrodites, a magazine designed “to exhume and exhibit everything the bourgeois imagination had buried beneath heavy layers of shame,” a shame to which Kipnis is not immune, though she is, like many of us, “theoretically” against all those repressions. She finds Flynt a worthy subject, his “self-styled war against social hypocrisy,” his “echt-Rabelaisian” assaults on decency precisely as revolting as they need be to show the middle-class imagination to itself. She calls herself “kind of a fan.”

This is not the approach of director Milos Forman, who chooses to make a movie that “sanitizes Flynt’s cantankerous, contrarian life and career into one long, noble crusade for the First Amendment, while erasing everything that’s most interesting about the magazine, namely the way it links bourgeois bodily discretion to political and social hypocrisy.” In other words, Forman took a complicated outsider and reduced him to a redemption story with which pious liberals could live. It was a story Flynt came to like. “America hadn’t been content with simply paralyzing Flynt,” muses Kipnis, “it had to finish the job by reconfiguring him as a patriot and then dousing him in approval for finally growing up. That’s how they get you.”

This theme, of radical malcontents swept into the ranks of the rule-following hordes, of anarchic impulses quelled and awkward histories rewritten, is not limited to Flynt. Kipnis is drawn to obsessive men, in particular obsessive men with bizarre or taboo obsessions. There is, for instance, the photographer Ron Galella, who was said to have made a “curious, grunting sound” whenever he caught a shot of his preferred subject, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. Galella trailed her on foot while shouting her name, tailed her in taxis, dated her maid, violated a restraining order mandating that he keep fifty feet away, and sued when secret-service agents interfered with what he deemed “photography” and many would call stalking. Four decades later, Galella was the subject of a 2012 retrospective in Berlin, admiring critical essays, a $300 book of photos (Jackie: My Obsession), and a documentary that spends a curious amount of time exploring the photographer’s interest in artificial flowers. There is a montage of Ron rolling around in bed with his pet rabbits. Says Galella, “They’re cleaner than cats.”

To which Kipnis rightly asks: “What’s with all the fucking bunnies?” Here again was a man made safe, the air of menace softened to mere eccentricity. His admirers seek to “sentimentalize away the aggression and egotism of art,” as if appreciating an artist’s work also entailed transforming him into an acceptable dinner date.

There is much fun to be had in experiencing the way that Kipnis follows her topics into unexpected territory, which is not unrelated to her charming inability to be the kind of easily outraged critic the world often seems to want. (“I mean, how come when they were handing out moral seriousness, Leon Wieseltier got so much and I got so little?” she asks.) The Marxist who accuses Kipnis of being too bourgeois to sleep with him follows up with a condescending letter six months after their nonaffair; she replies, accusing him of being a leftist cliché; he, pointing out that they were sitting on her bed, accuses her of trying to turn a romantic evening into “history itself”: a “battle between Feminism and the Male Left.” What was she doing sitting on her bed with him, Kipnis wonders years later. “The locale seems awfully equivocal.” This all takes place within the context of an essay on the self-delusion of John Edwards, which becomes an essay on the physical ugliness of Jean-Paul Sartre, which becomes an essay on Bad Faith.

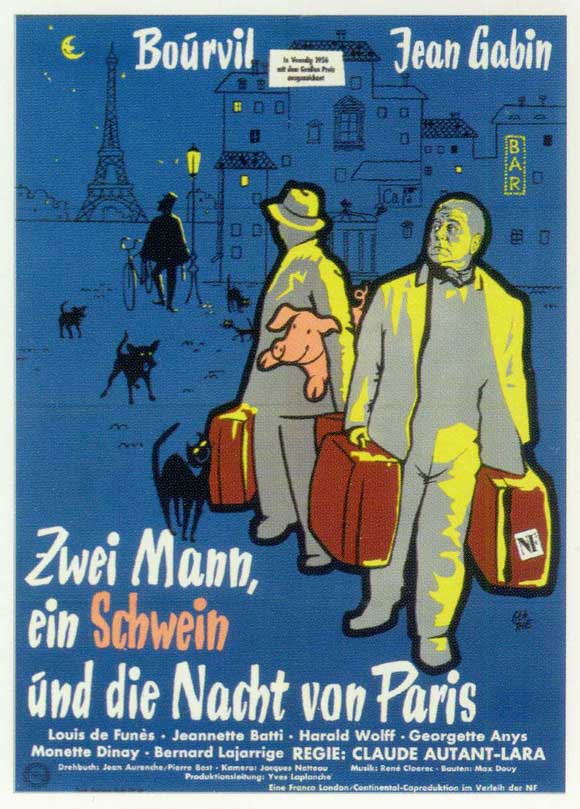

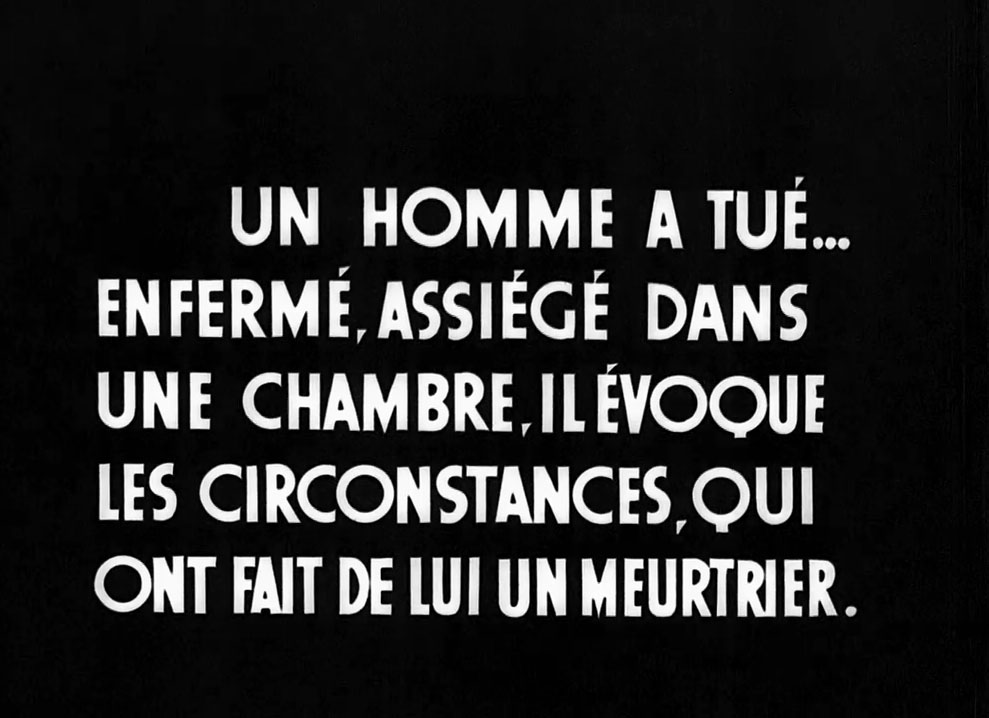

Card from Le Jour Se Lève (1939)

Story arc

Guccio Gucci

As a teenager in the early 1900s, Guccio Gucci was a lift boy at the Savoy Hotel in London. Inspired by the elegant upperclass guests, he returned to Florence and started making travel bags and accessories. He founded the House of Gucci in Florence in 1921[1] as a small family-owned leather saddlery shop. He began selling leather bags to horsemen in the 1920s. As a young man, he rapidly built a reputation for quality, hiring the best craftsmen he could find to work in his atelier.[1] In 1938, Gucci expanded his business to Rome. Soon his one-man business turned into a family business, when his sons Aldo, Vasco, Ugo and Rodolfo joined the company.

Aldo Gucci

From the age of 20, Aldo began work full-time at Gucci. He went on to open the first shop outside his native city in Rome in 1938[2] and soon after took over the reins of the company upon his father’s death in 1953. Gucci became an overnight status symbol when the bamboo handbag was featured on Ingrid Bergman’s arm in Roberto Rossellini’s 1954 film “Viaggio in Italia”. The GG insignia became an instant favorite of Hollywood celebrities and European royalty. When Aldo opened in New York in 1953, he planted the “Made in Italy” flag on American soil for the first time. President John F Kennedy heralded him as the first Italian Ambassador to fashion[3] and he was awarded an honorary degree by the City University of New York in recognition of his philanthropic activity, described as the Michelangelo of Merchandising.[4] He went on to open shops in Chicago, Palm Beach and Beverly Hills, before expanding to Tokyo, Hong Kong and in cities around the world through a global franchising network. For over thirty years he was dedicated to the expansion of Gucci, developing the company into a vertically integrated business with its own tanneries, manufacturing and retail premises. In 1986 he was sentenced to one year and one day in prison for tax evasion in New York. He was 81.[5] He did his time at the Federal Prison Camp at Eglin Air Force Base, Florida. In 1987, after 66 years as a family-owned business, Gucci was sold to Investcorp.[6]

Michael Clune’s memoir [White Out: The Secret Life of Heroin] opens a few years into his habit. He is visiting some addict friends, Dominic and Henry, in Baltimore. Henry has one arm; Dominic has a syringe sticking out of his neck. Clune has come to ask them for OxyContin, but what he really wants is heroin, ‘the white thing’. He sees a ‘half-empty white-topped vial’ on the table and starts thinking about the colour white: white Jesus, the white moon, the white teeth in Dominic’s ‘gaping red snoring mouth’, the white stoppers in the vials of Baltimore’s best heroin:

The power of dope comes from the first time you do it. It’s a deep memory disease. People know the first time is important, but mostly they’re confused about why. Some think addiction is nostalgia for the first mind-blowing time. They think the addict’s problem is wanting something that happened a long time ago to come back. That’s not it at all. The addict’s problem is that something that happened a long time ago never goes away. To me, the white tops are still as new and fresh as the first time. It still is the first time in the white of the white tops.

He also writes about his theory of addiction, in which the colour white takes on several meanings. As well as the colour of heroin powder and of the stopper in that first vial it’s also the blank memory space that allows him to believe that the first time has, in a way, never happened, and so means that dope never gets old. The novelty doesn’t come from the feeling of doing the drug, which Clune says ‘starts to suck pretty quickly’. Instead it’s the image, and the persistent newness of the image, that keeps him coming back:

Something that’s always new, that’s immune to habit, that never gets old. That’s something worth having. Because habit is what destroys the world. Take a new car and put it in an air-controlled garage. Go look at it every day. After one year all that will remain of the car is a vague outline. Trees, stop signs, people and books grow old, crumble and disappear inside our habits. The reason old people don’t mind dying is because by the time you reach eighty, the world has basically disappeared.

A collaboration in every sense of the word from husband-and-wife team Ben Sinclair and Katja Blichfeld, the hit web series High Maintenance follows a cannabis dealer known simply as “The Guy” (Sinclair) as he slips in and out of the lives of his clients—an eclectic array of Brooklynites, ranging from a harried personal assistant buying weed for her boss to a misunderstood asexual magician.

Featuring cameos by actors Dan Stevens (Downton Abbey) and Hannibal Buress (Broad City), this “absorbing and keenly observed” (Entertainment Weekly) comedy series comes to BAMcinématek for a screening of previous highlights and the premiere of “Geiger,” a new episode featuring Sinclair, Tanisha Long, and William Jackson Harper. This episode will be available exclusively on Vimeo-On-Demand beginning November 11.

A. A. Milne: the celeries of Autumn

from Not That It Matters (1920)

Last night the waiter put the celery on with the cheese, and I knew that summer was indeed dead. Other signs of autumn there may be—the reddening leaf, the chill in the early-morning air, the misty evenings—but none of these comes home to me so truly. There may be cool mornings in July; in a year of drought the leaves may change before their time; it is only with the first celery that summer is over.

I knew all along that it would not last. Even in April I was saying that winter would soon be here. Yet somehow it had begun to seem possible lately that a miracle might happen, that summer might drift on and on through the months—a final upheaval to crown a wonderful year. The celery settled that. Last night with the celery autumn came into its own.

There is a crispness about celery that is of the essence of October. It is as fresh and clean as a rainy day after a spell of heat. It crackles pleasantly in the mouth. Moreover it is excellent, I am told, for the complexion. One is always hearing of things which are good for the complexion, but there is no doubt that celery stands high on the list. After the burns and freckles of summer one is in need of something. How good that celery should be there at one’s elbow.

A week ago—(“A little more cheese, waiter”)—a week ago I grieved for the dying summer. I wondered how I could possibly bear the waiting—the eight long months till May. In vain to comfort myself with the thought that I could get through more work in the winter undistracted by thoughts of cricket grounds and country houses. In vain, equally, to tell myself that I could stay in bed later in the mornings. Even the thought of after-breakfast pipes in front of the fire left me cold. But now, suddenly, I am reconciled to autumn. I see quite clearly that all good things must come to an end. The summer has been splendid, but it has lasted long enough. This morning I welcomed the chill in the air; this morning I viewed the falling leaves with cheerfulness; and this morning I said to myself, “Why, of course, I’ll have celery for lunch.” (“More bread, waiter.”)

“Season of mists and mellow fruitfulness,” said Keats, not actually picking out celery in so many words, but plainly including it in the general blessings of the autumn. Yet what an opportunity he missed by not concentrating on that precious root. Apples, grapes, nuts, and vegetable marrows he mentions specially—and how poor a selection! For apples and grapes are not typical of any month, so ubiquitous are they, vegetable marrows are vegetables pour rire and have no place in any serious consideration of the seasons, while as for nuts, have we not a national song which asserts distinctly, “Here we go gathering nuts in May”? Season of mists and mellow celery, then let it be. A pat of butter underneath the bough, a wedge of cheese, a loaf of bread and—Thou.

How delicate are the tender shoots unfolded layer by layer. Of what a whiteness is the last baby one of all, of what a sweetness his flavor. It is well that this should be the last rite of the meal—finis coronat opus—so that we may go straight on to the business of the pipe. Celery demands a pipe rather than a cigar, and it can be eaten better in an inn or a London tavern than in the home. Yes, and it should be eaten alone, for it is the only food which one really wants to hear oneself eat. Besides, in company one may have to consider the wants of others. Celery is not a thing to share with any man. Alone in your country inn you may call for the celery; but if you are wise you will see that no other traveler wanders into the room. Take warning from one who has learnt a lesson. One day I lunched alone at an inn, finishing with cheese and celery. Another traveler came in and lunched too. We did not speak—I was busy with my celery. From the other end of the table he reached across for the cheese. That was all right! it was the public cheese. But he also reached across for the celery—my private celery for which I owed. Foolishly—you know how one does—I had left the sweetest and crispest shoots till the last, tantalizing myself pleasantly with the thought of them. Horror! to see them snatched from me by a stranger. He realized later what he had done and apologized, but of what good is an apology in such circumstances? Yet at least the tragedy was not without its value. Now one remembers to lock the door.

Yes, I can face the winter with calm. I suppose I had forgotten what it was really like. I had been thinking of the winter as a horrid wet, dreary time fit only for professional football. Now I can see other things—crisp and sparkling days, long pleasant evenings, cheery fires. Good work shall be done this winter. Life shall be lived well. The end of the summer is not the end of the world. Here’s to October—and, waiter, some more celery.