From Terry Eagleton on John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester

Bored by his country residence and deaf to his wife’s pleas for his company, [Rochester] spent his time in London brawling, drinking and whoring along with fellow members of a secret club known as the Ballers, which imported leather dildos to use in their entertainments. Impeccably egalitarian in his sexual favours, Rochester slept with everyone from court ladies to prostitutes in the cheapest brothels in town. He probably had affairs with men as well; few courtiers of the time did not. Homosexuality was intensely fashionable, despite being a capital crime on a level with treason. The socially inept John Dryden, in a feeble attempt to keep abreast of a group of fast-living companions, once blurted out: ‘Let’s bugger one another now, by God.’ At one point Rochester took as his valet a young Frenchman called Belle Fasse (possibly a pun on ‘belles fesses’ or ‘beautiful buttocks’), and probably bedded him – a reckless dalliance, given that Belle Fasse was a Catholic.

Though he was rapidly moving from sprightly young blade to raddled old lecher, his reputation as a wit, poet, daredevil lover and brilliant conversationalist was riding high. He lived in theatrical style, delighting in masks and flamboyant costumes, and now the theatre began to imitate his life. He became the model for a number of raffish characters, most notably Dorimant in George Etherege’s The Man of Mode. No Restoration comedy was complete without its Rochester lookalike. He also fell in love with another would-be actor, Elizabeth Barry, and soon found himself at sea in an ocean of Elizabeths. Barry had a daughter by him to whom she gave her own first name, and Rochester gave the same name to one of his daughters with his wife Elizabeth, perhaps as a sly joke at her expense.

There was a streak of madness about Rochester, a perverse, Wilde-like impulse to self-destruction. Rather as Wilde appeared to be courting disaster, so Rochester seemed to do his best to enrage the monarch on whom his fortunes depended. When Charles asked to see a satirical poem that was circulating around the court, Rochester handed him instead a vituperative lampoon of the king he had written himself. Whether he did this by accident or design is unclear. Perhaps it was a Freudian parapraxis, consciously accidental but unconsciously intended. In any case, Charles was furious, Rochester was banished from the court yet again and his various pensions and salaries suspended. He was reinstated some time later, only to be pitched out once more when in another bout of insanity he threw himself in a drunken rage on a phallic-shaped sundial dear to the king’s heart crying, ‘What! Do you stand here to fuck time?’ and slashed it to pieces with his rapier. It was said to be the most elaborate and expensive instrument of its kind in Western Europe.

As the syphilis addled his brain he grew odder and odder. Extraordinarily, he disguised himself for a few months as a gorgeously attired Italian physician, Alexander Bendo, and set up shop in a London street offering cures for scurvy, back pain, bad teeth, obesity, consumption, kidney stones and a number of other afflictions. His work required him on occasion to see his female patients naked, and if his more respectable women clients were shy of being intimately examined by him, he would sometimes do so disguised as Mrs Bendo. In his own person, he would also occasionally offer a cure for infertility by a strikingly simple technique.

For “Goodbye to Language 3D,” opening on Wednesday, [Godard] encouraged his cinematographer, Fabrice Aragno, to build customized camera rigs (much as, a half-century ago, he asked Raoul Coutard to use still-photography stock to shoot at night for “Breathless”). Mr. Aragno said in an interview that Mr. Godard had watched “Avatar” and “Piranha 3D.” In Paris, the two saw a live 3-D theatrical broadcast of the 2010 World Cup, which piqued the director’s interest: “He said, ‘It’s incredible because we see everything like puppets,’ ” Mr. Aragno recalled.

Fan video for Ariel Pink, “Beverly Kills” (2010)

George Plimpton, from a letter to Terry Southern, 1957

I’m delighted to hear from Bob that you have undertaken an interview with Henry Green. I meant to write you last spring that I had tea with him in London—with his wife, some others, and Christopher Logue, that frenetic poet whom you may remember from Paris and who worships Green and begged to be taken along. Well, he was, and there was Green in a double-breasted black business suit going under the name York (sic), talking like a businessman from Manchester, with an anecdote or two, terribly long—one, as I remember, about a seal two old ladies found on a beach near Brighton and nursed back to health in their bathtub, the point of the story being that in England alone could such a thing happen. Logue kept darting looks at the door, for Green, I guess, and making side remarks of incredible rudeness to York. When we left, Logue asked: “Jesus, who the fuck was that guy on the sofa.” “Henry Green,” I said.

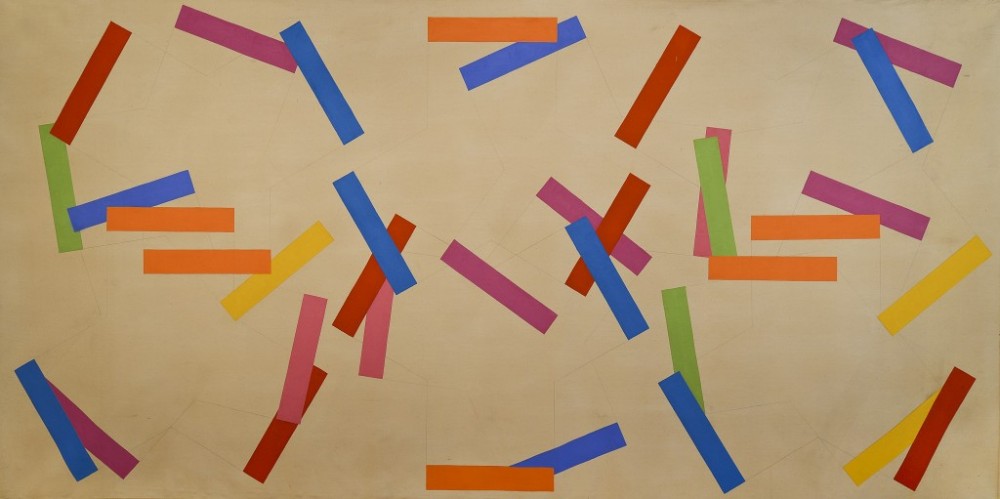

Ellsworth Kelly's Dream of Impersonality

Kelly’s use of cropping has nothing to do with this paean to the subjective and transitory nature of experience—especially since, as one must always remember, what he crops is always flat (if it involves the visual field, and not, as is most often the case, a particular surface in it, it is the visual field as perceived with only one eye). More importantly, perhaps, is the fact that the cropping is itself an involuntary accident, almost like a hiccup or a Freudian slip of the tongue—the sudden “apparition” of a shape as it strikes a chord for being unrecognizable, for being recognized as something the artist consciously knows it is not. Either this shape echoes something already caught in the web of the matrix, or it appeals to Kelly for its potentiality as a score for a new piece, but a score whose material performance in the real world, an “already-made” unperceived by anyone but him, is only the material proof that it can, indeed, exist on its own. The process by which the “already-made” shape is suddenly available to Kelly—while it escapes most of us—is one of defamiliarization, of what the Russian formalists called ostranenie. It came upon the young Kelly years before he became an artist, and the strong memories he has about several childhood experiences is perhaps the reason his work remains so fresh. I’ll quote two such memories, but there are many more:

I remember that when I was about ten or twelve years old I was ill and fainted. And when I came to, my head was upside down. I looked at the room upside down, and, for a brief moment I couldn’t understand anything until my mind realized that I was upside down and I righted myself. But for the moment that I didn’t know where I was, it was fascinating. It was like a wonderful world.

And this, recalled by Hugh Davies, Director of the San Diego Museum of Contemporary Art:

On Halloween night in 1935, in rural Oradell, New Jersey, the twelve-year-old Ellsworth Kelly was trick-or-treating with friends in their neighborhood after dark. Upon approaching a house from a distance, he said: “I saw three colored shapes—red, black, and blue—in a ground-floor window. It confused me and I thought: ‘What is that?’ When I got close to the window, it was too high to look in easily and I didn’t want to be peeking. I was very curious and came at the window obliquely, and chinned myself up, only to look into a normal furnished living room. When I backed off to a distance, there it was again. I now realize that this was probably my first abstract vision—something like the three shapes in your Red Blue Green painting.”

The cropped view of a bourgeois interior seen by the young Kelly as peeping Tom is not the “source” of the San Diego painting. But these recollections offer perfect examples of the kind of defamiliarization allowed by the matrix, a kind of defamiliarization wonderfully analyzed by Maurice Merleau-Ponty in the Phenomenology of Perception, when he wrote that “to put an object upside down is to remove its signification from it” and noted how difficult it is, when walking along an avenue, “to see the spaces between the trees as things and the trees themselves as background.”

Recipe: At-Home Cronut

From the kitchen of Dominique Ansel

Servings: Over 8

Cook Time: Over 120 minutes

Difficulty: Extreme

Two Days Before

Make ganache: Prepare one of the ganache recipes below and refrigerate until needed.

Make pastry dough: Combine the bread flour, salt, sugar, yeast, water, egg whites, butter, and cream in a stand mixer fitted with a dough hook. Mix until just combined, about 3 minutes. When finished the dough will be rough and have very little gluten development.

Lightly grease a medium bowl with nonstick cooking spray. Transfer the dough to the bowl. Cover with plastic wrap pressed directly on the surface of the dough, to prevent a skin from forming. Proof the dough in a warm spot until doubled in size, 2 to 3 hours.

Remove the plastic wrap and punch down the dough by folding the edges into the center, releasing as much of the gas as possible. On a piece of parchment paper, shape into a 10-inch (25 cm) square. Transfer to a sheet pan, still on the parchment paper, and cover with plastic wrap. Refrigerate overnight.

Make butter block: Draw a 7-inch (18 cm) square on a piece of parchment paper with a pencil. Flip the parchment over so that the butter won’t come in contact with the pencil marks. Place the butter in the center of the square and spread it evenly with an offset spatula to fill the square. Refrigerate overnight.

One Day Before

Laminate: Remove the butter from the refrigerator. It should still be soft enough to bend slightly without cracking. If it is still too firm, lightly beat it with a rolling pin on a lightly floured work surface until it becomes pliable. Make sure to press the butter back to its original 7-inch (18 cm) square after working it.

Remove the dough from the refrigerator, making sure it is very cold throughout. Place the dough on a floured work surface. Using the rolling pin, roll out the dough to a 10-inch (25.5 cm) square about 1 inch (2.5 cm) thick. Arrange the butter block in the center of the dough so it looks like a diamond in the center of the square (rotated 45 degrees, with the corners of the butter block facing the center of the dough sides). Pull the corners of the dough up and over to the center of the butter block. Pinch the seams of dough together to seal the butter inside. You should have a square slightly larger than the butter block.

Very lightly dust the work surface with flour to ensure the dough doesn’t stick. With a rolling pin, using steady, even pressure, roll out the dough from the center. When finished, you should have a 20-inch (50 cm) square about 1/4-inch (6 mm) thick. (This is not the typical lamination technique and is unique to this recipe. When rolling out dough, you want to use as little flour as possible. The more flour you incorporate into the dough, the tougher it will be to roll out, and when you fry the At-Home Cronut pastries they will flake apart.)

Fold the dough in half horizontally, making sure to line up the edges so you are left with a rectangle. Then fold the dough vertically. You should have a 10-inch (25.5 cm) square of dough with 4 layers. Wrap tightly in plastic wrap and refrigerate for 1 hour.

Repeat steps 3 and 4. Cover tightly with plastic wrap and refrigerate overnight.

The Day Of

Cut dough: On a lightly floured work surface, roll out the dough to a 15-inch (40 cm) square about 1/2-inch (1.3 cm) thick. Transfer the dough to a half sheet pan, cover with plastic wrap, and refrigerate for 1 hour to relax.

Using a 3 1/2-inch (9 cm) ring cutter, cut 12 rounds. Cut out the center of each round with a 1-inch (2.5 cm) ring cutter to create the doughnut shape.

Line a sheet pan with parchment paper and lightly dust the parchment with flour. Place the At-Home Cronut pastries on the pan, spacing them about 3 inches (8 cm) apart. Lightly spray a piece of plastic wrap with nonstick spray and lay it on top of the pastries. Proof in a warm spot until tripled in size, about 2 hours. (It’s best to proof At-Home Cronut pastries in a warm, humid place. But if the proofing area is too warm, the butter will melt, so do not place the pastries on top of the oven or near another direct source of heat.

Fry dough: Heat the grapeseed oil in a large pot until it reaches 350 degrees F (175 degrees C). Use a deep-frying thermometer to verify that the oil is at the right temperature. (The temperature of the oil is very important to the frying process. If it is too low, the pastries will be greasy; too high, the inside will be undercooked while the outside is burnt.) Line a platter with several layers of paper towels for draining the pastries.

Gently place 3 or 4 of them at a time into the hot oil. Fry for about 90 seconds on each side, flipping once, until golden brown. Remove from the oil with a slotted spoon and drain on the paper towels.

Check that the oil is at the right temperature. If not, let it heat up again before frying the next batch. Continue until all of them are fried.

Let cool completely before filling.

Make glaze: Prepare the glaze below that corresponds to your choice of ganache.

Make flavored sugar: Prepare the decorating sugar on page 208 that corresponds to your choice of ganache.

Assemble: Transfer the ganache to a stand mixer fitted with a whisk. Whip on high speed until the ganache holds a stiff peak. (If using the Champagne-chocolate ganache, simply whisk it until smooth. It will be quite thick already.)

Cut the tip of a piping bag to snugly fit the Bismarck tip. Using a rubber spatula, place 2 large scoops of ganache in a piping bag so that it is one-third full. Push the ganache down toward the tip of the bag.

Place the decorating sugar that corresponds to your choice of ganache and glaze in a bowl.

Arrange each At-Home Cronut pastry so that the flatter side is facing up. Inject the ganache through the top of the pastry in four different spots, evenly spaced. As you pipe the ganache, you should feel the pastry getting heavier in your hand.

Place the pastry on its side. Roll in the corresponding sugar, coating the outside edges.

If the glaze has cooled, microwave it for a few seconds to warm until soft. Cut the tip of a piping bag to snugly fit a #803 plain tip. Using a rubber spatula, transfer the glaze to the bag. Push the glaze down toward the tip of the bag.

Pipe a ring of glaze around the top of each At-Home Cronut pastry, making sure to cover all the holes created from the filling. Keep in mind that the glaze will continue to spread slightly as it cools. Let the glaze set for about 15 minutes before serving.

Serving instructions: Because the At-Home Cronut pastry is cream-filled, it must be served at room temperature.

Storage instructions: Consume within 8 hours of frying. Leftover ganache can be stored in a closed airtight container in the refrigerator for 2 days. Leftover flavored sugar can keep in a closed airtight container for weeks and can be used to macerate fruits or sweeten drinks.