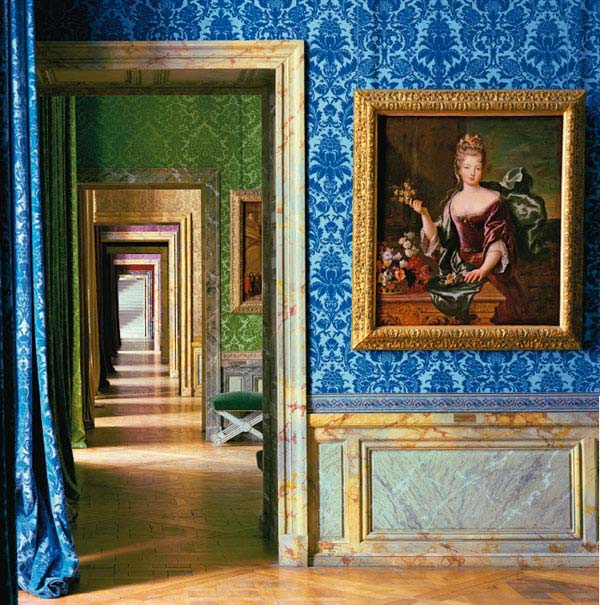

Enfilade

Robert Polidori, Detail from A Portrait of Françoise-Marie de Bourbon, Duchess d’Orleans, Chateau de Versailles, 1991. Color photograph, 50 × 40 inches.

Baroque royal and aristocratic design gave visual expression to the principles of absolute rule. During the Baroque era, France and England each endured civil wars that pitted the nobility against the throne. When absolute monarchical rule was reestablished after these uprisings, many royal architectural commissions reflected a programmatic emphasis on strict hierarchies with the King at the top. Within the Baroque palace, the enfilade [pronounced EN-fuh-LAHD or EN-fuh-LAYD] emphasized the careful and unyielding organization of the interior and, by extension, the state. This was in some ways totally symbolic — the straight line suggesting order, the endless sightlines underlining the luxury of the space and the King’s vast resources. But in other ways it was utterly literal. Each room was successively more exclusive, with access limited more and more according to your rank within the court. Part of this was simply practical: the first room in the enfilade was an entry hall and the last would be the state bedroom, so it naturally became more intimate as you progressed. But even details like whether you were guided through by a servant or by your host, where you were met (at the door or in the middle of the room), and other minutiae, were carefully considered and noticed.