The cyberpragmatics of bounding asterisks

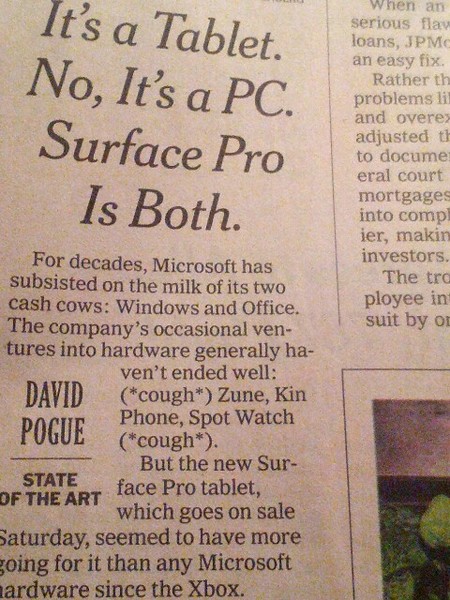

On Daring Fireball, John Gruber noticed something interesting about David Pogue's New York Times review of the Surface Pro: what he calls "the use of bounding asterisks for emphasis around the coughs." Pogue wrote:

For decades, Microsoft has subsisted on the milk of its two cash cows: Windows and Office. The company’s occasional ventures into hardware generally haven’t ended well: (*cough*) Zune, Kin Phone, Spot Watch (*cough*).

And the asterisks weren't just in the online version of the Times article. Here it is in print (via Aaron Pressman):

By "emphasis" Gruber explains that he means "informing the reader of a shift in style or voice," likening the use of bounding asterisks to "how foreign words are italicized in many publications and books." He figured it was an "Internet-ism," tracing its use to the need for a plain-text substitution for italicization or bolding.

But David Friedman pointed out on Twitter that one could use the Google Books Ngram Viewer to search for such strings as *cough* and *sigh*, because the Ngram corpus tokenizes asterisks along with other punctuation. A search reveals *cough* on the rise from around 1990 (fitting Gruber's impression of the convention as an Internet-ism), but *sigh* actually starts showing up in the mid-'60s. Friedman chalked up the early use of *sigh* to the comic strip "Peanuts." Charles Schulz made frequent use of sigh as an exclamation, especially by Charlie Brown, with the word bounded by star-shaped symbols (not quite asterisks).

Let's take a look at the prehistory of *cough*-style asterisking in comic strips, and the more recent usage as a form of "cyberpragmatics."

In comic strips of the early to mid-20th century, cartoonists often needed to represent expressive non-verbal noises in the characters' speech balloons. This was typically done with the use of such words as sob, sniff, cough, hack, wheeze, gasp, gulp, choke, and gag. Such interjections came to be used as a form of onomatopoeia, alongside more directly onomatopoetic expressions like ahem, ugh, ooh, whew, and zzz. When they appeared in the comics, they typically followed the convention one would find in other print sources of the era: bounding by parentheses.

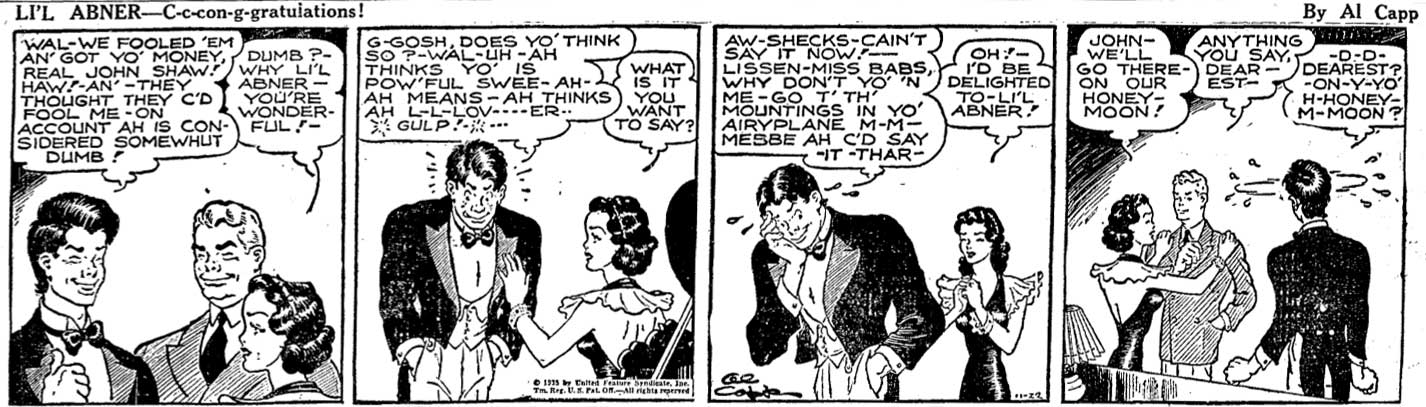

Sometimes other delimiters were used. Comic strips have been getting creative with typography since the early days — consider the rise of cursing characters or "obscenicons" (aka "grawlixes"), which I've traced back to 1902. The earliest example I've found so far of "Peanuts"-style starburst characters is in this "Li'l Abner" strip from Nov. 22, 1935, where they appear around gulp!:

Perhaps Schulz borrowed this stylization from "Li'l Abner." Whatever the source, he began using it in "Peanuts" early on — here it is from Nov. 26, 1951, about a year after the strip premiered:

(That's an appreciative sigh from Schroeder, as opposed to the world-weary sigh that Charlie Brown would come to be known for.)

Using Michael Yingling's "Calvin and Hobbes" search engine (which allows punctuation searches), we can see that Bill Watterson carried on the Schulzian tradition, with similar starburst characters (around sniff, gasp, sob, sighhh, gulp, etc.).

Now let's skip ahead to Internet usage. Gruber characterized the use of bounding asterisks in online communication as a form of emphasis, but pragmatically it's a bit more complex than that. True, bounding asterisks can emphasize a word or words in plain-text messages where italics and bolding are unavailable, but the legacy of the comic strips points in another direction — the use of bounding asterisks to signal non-verbal noises or actions as a kind of self-describing stage direction.

Francisco Yus nicely summarizes this type of asterisk use in his book Cyberpragmatics: Internet-Mediated Communication in Context (John Benjamins, 2011, p. 173):

Autonomous stage direction. It occurs when the user's nonverbal behaviour is expressed with its closest translation, normally in one or two words, and framed by asterisks that separate it for the verbal content that they accompany. It is defined by Herring (forthcoming) as "predications that can function alone as complete performative utterances." An example is quoted below:

(20) What you're saying is funny *laugh*

In general, users resort to typical terms that once can find in a dictionary as prototypical of the equivalent nonverbal behaviour. Therefore, they vary inter-culturally depending on the lexical repertoire that languages offer for the description of nonverbal behaviour.

(The cited source is: Herring, Susan C. "Grammar and electronic communication." In The Encyclopledia of Applied Linguistics, Carol A. Chapelle (ed.), Wiley-Blackwell, 2012.)

What's fascinating about these asterisked stage directions is that they have moved well beyond the onomatopoetic coughs, gulps, and sighs of the comic strips into more complex actions stated in the third person, such as *jumps up and down*. In an email, Jason Treit describes them as "performative":

They set up an active contruction where the writer switches to third person, as if subjecting themselves to the verb or verb phrase in the moment of typing it. Usually there's even subject-verb agreement with the third person pronoun: think *hangs upside down like a bat*.

Old Facebook status updates or the /me command in IRC [Internet Relay Chat] work on the same valence.

The origins of such usage likely can be found in text-based role-playing games in MUDs (Multi-User Dungeons/Domains), which were superseded by IRC and instant-messaging interfaces. As one "Role Play Manual of Style" explains, "Actions are enclosed in asterisks and written in third person perspective." But this type of asterisking has thoroughly infected Usenet posts, blog comments, tweets, and anywhere else online that people feel the need to describe real-world actions in a virtual space.

So, by giving yourself your own stage directions enclosed in asterisks, you treat your own words as lines in a play, and then step outside of your character to give the perspective of the playwright in the play you're acting in. It's all so meta. If Erving Goffman were alive, he'd love this stuff.