Search for ‘MATT ’ (136 articles found)

'Frame is part of drawing'

How do we know what we know, and when?

For instance, we know that Erased de Kooning Drawing (1953) is one of Robert Rauschenberg’s most important, influential works. It’s the kind of commonly accepted history that lands a piece in the Final Four of Tyler Green’s Art Madness poll to determine America’s Greatest Post-War Artwork.

And we know the story of it, how Bob took a bottle of liquor with him to Bill’s studio to ask for a drawing to erase. And how Bill, at first reluctant, twice-validated the sacrifice by giving away “a drawing he’d miss” and which would be “hard” for Bob to erase. And then Bob signed it and framed it and sparked an art world scandal with it which hasn’t really abated. We know this because Bob and then his curator and critic advocates repeat the story so frequently. [Vincent Katz has a nice telling of it in Tate Magazine in Autumn 2006.]

But this weekend, I suddenly had cause to wonder just how all this went down, and when, really, did this revolution start? Because it’s not as clear or as obvious as I had always assumed.

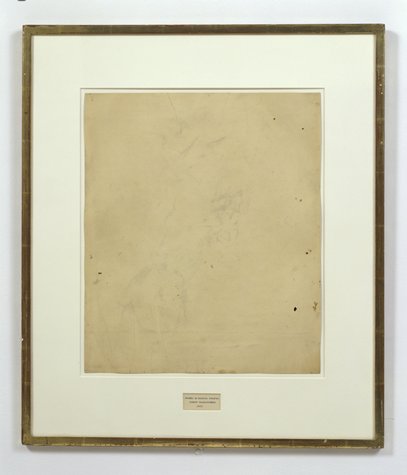

That’s Erased de Kooning Drawing up there, precisely matted and framed. That’s how I saw it for the first time in Walter Hopps’ “Rauschenberg In The Early 1950s” show at the Menil 20 years ago, and then again in John Cage’s “Rolywholyover” a couple of years after that. [Or am I conflating the two Guggenheim SoHo versions of those shows?]

At the time, it was still in the artist’s own collection. In 1998, SFMOMA acquired it along with a group of other Rauschenberg works. [Calvin Tomkins wrote in the New Yorker in 2005 that MoMA was offered the works first and turned them down.] Its official description: “drawing | traces of ink and crayon on paper, mat, label, and gilded frame.” It’s not just a drawing, not just an erased drawing, it’s an object assembled.

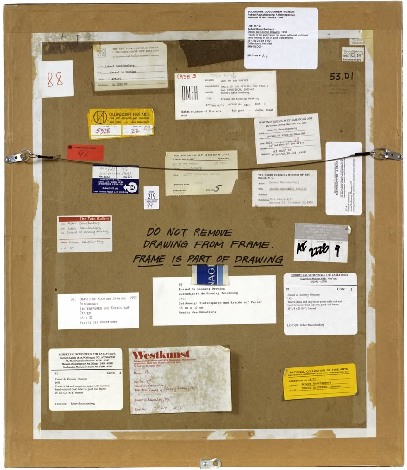

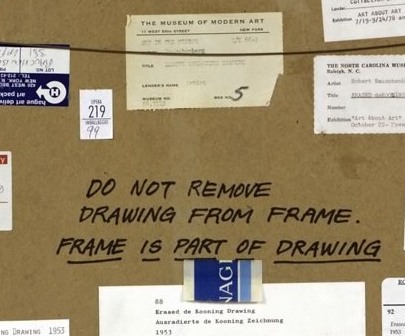

SFMOMA has a nice little, c.2000 interactive that includes the back of the piece:

“DO NOT REMOVE

DRAWING FROM FRAME

FRAME IS PART OF DRAWING“

LOVE THAT. I could geek out staring at the backs of artworks all day. Did Bob himself write that? It looks like it.

The early line on Erased de Kooning was either “neo-dada,” which was a standard critical reaction to Rauschenberg in the 50s, or AbEx patricide. But it has since evolved far beyond these bad boy, enfant terrible readings, to be considered a precursor of huge swaths of contemporary art.

In his 2009 book, Random Order: Robert Rauschenberg and the Neo-Avant-Garde, Branden Joseph discussed Erased de Kooning Drawing as one of the touchstones of conceptual art and appropriation art, alongside Marcel Duchamp’s mustache-on-the-Mona-Lisa, L.H.O.O.Q:

Whether by defacement or effacement, the two works’ devalutaion of the appropriated representation (an essential factor in the process of allegorization) is equally effective. Rauschenberg’s subsequent mounting of the erased sheet of paper within a gold frame, together with the adition of a carefully hand-lettered label with a new authorial attribution, title, and date (“Erased de Kooning drawing / Robert Rauschenberg / 1953”), simultaneously doubles the visual text with a new signification and calls attention away from the (now depleted) visual aspect of the work and toward the conventional and institutional devices of the work’s “framing.”…For Rauschenberg’s Erased de Kooning Drawing essentially reenacted the reception of his White Paintings: the initial evacuation of expressive or representational meaning in favor of transitional, temporal forces subsequently gave way to a process in which meaning was reattributed to the work from the outside.

Indeed it was. As the White Paintings were to the reflections and shadows in the room, so Erased de Kooning Drawing was to passing theories of art.

In 1976 Bernice Rose put “the famous Erased de Kooning drawing” along side Jasper Johns’ Diver at the foundation of The Modern’s major survey, “Drawing Now.” Reviewing the show for the New Yorker, Harold Rosenberg dismissively labeled Pop, Minimalism and Conceptualism, the work that followed Rauschenberg’s and Johns’s “parodies of Action painting,” as the new “Academy of the Erased de Kooning.”

Later that year, the drawing was in Walter Hopps’ Rauschenberg Retrospective at the Smithsonian, which traveled back, in 1977, to MoMA. Where it prompted Grace Glueck to open her NY Times story with a rhetorical question—“Wasn’t it only a couple of years ago that Robert Rauschenberg erased a drawing by Willem de Kooning?”

Yes, only a couple, give or take twenty four. Maybe it just took that long to get it. We had to wait for Conceptualism to be invented before anyone could recognize Erased de Kooning was its foundation.

In the September 1982 issue of Artforum, none other than Benjamin Buchloh discussed Erased de Kooning Drawing‘s historical importance in a sprawling 14-page essay titled, “Allegorical Procedures: Appropriation and Montage in Contemporary Art”:

At the climax of the Abstract Expressionist idiom and its reign in the art world this may have been perceived as a sublimated patricidal assault by the new generations most advanced artists, but it now appears to have been one of the first examples of allegorization in post-New York School art. It can be recognized as such in its procedures of appropriation, the depletion of the confiscated image, the superimposition or doubling of a visual text by a second text, and the shift of attention and reading to the framing device. Rauschenberg’s appropriation confronts two paradigms of drawing: that of de Kooning’s denotative lines, and that of the indexical functions of the erasure. Production procedures (gesture), expression, and sign (representation) seem to have become materially and semantically congruent. Where perceptual data are withheld or removed from the traditional surface of display, the gesture of erasure shifts the focus of attention to the appropriated historical constrict on the one hand, and to the devices of framing and presentation, on the other.

Whew. But.

Back up. Because here is Buchloh’s account of the gesture, and of the “device of framing and presentation”:

After the careful execution of the erasure, which left vestiges of pencil and the imprint of the drawn lines visible as clues of visual recognizability, the drawing was framed in a gold frame. An engraved metal label attached to the frame identified the drawing as a work by Robert Rauschenberg entitled and dated 1953.

[Emphasis added because, WTF engraved metal label?] When did it have a metal label?

There wasn’t one in 1991 when I saw it. And there wasn’t one in 1976, when Walter Hopps wrote this catalogue entry: “He [Rauschenberg] then hand-lettered the title, date of the work, and his name on a label and placed the drawing in a gold-leaf frame bought specifically for it.” [Oddly, the only source Hopps cites is an Interview Magazine Q&A, dated May 1976

, just as the catalogue was being produced.]

There is no way that the hand-drawn label in the middle of the mat of Erased de Kooning Drawing could be mistaken for a metal label on a frame. At least if you had seen the work in person. Or had discussed it with anyone who had. So the implication, then, is that in 1982, Benjamin Buchloh had not actually seen Erased de Kooning Drawing, or that he’d misremembered it or misread a photo of it, and neither he nor anyone at the magazine of record noticed the error. Which does make some sense if Erased de Kooning is a conceptual work in the mode of Joseph Kosuth, not an art object, per se but an “idea of an art work [whose] formal components weren’t important.” [Of course, Kosuth said that in 1965, more than a decade after Rauschenberg apparently already demonstrated it.]

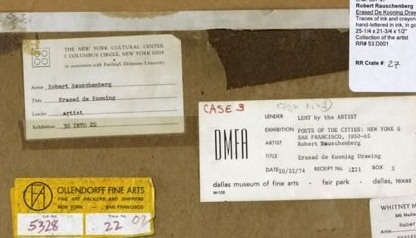

But there are some problems here. Judging by all the registrars’ labels and notes on the back, it seems impossible that someone like Benjamin Buchloh would not have seen Erased de Kooning Drawing in the 30 years since its creation. But looking more closely, I can’t find any exhibitions dating before 1973. That’s when Susan Ginsburg’s show, “3D Into 2D: Drawing For Sculpture,” opened at the New York Cultural Center. [Ginsburg was, among many other things, a board member of Change, Inc., an artist emergency assistance foundation Rauschenberg started in 1970.]

Was Erased de Kooning Drawing shown in the 60s? Or the 50s, for that matter? Where? How? What was the reaction? Because the triumphant Conceptualist historicization of the work seems to have obscured—if not actually erased—its early history.

A progress: or, one foot in front of the other

When we walk into the denuded Guggenheim, finally wiggling past Lloyd Wright’s low-ceilinged, dark and deliberately claustrophobia-inducing entrance foyer, it takes us a few seconds to adjust to all the open space spiraling upwards and outwards around us. There’s a couple, good-looking college kids or twenty-somethings, hetero, going at it on the floor of the atrium, near the fountain. The crowd gives them wide berth. They writhe sinuously, mouth to mouth, kissing or pretending to kiss, rising onto their knees, palms flat on the other’s backs. Their hands slide down with exaggerated slowness until the palms rest flat on the floor, the first sign that there’s something artificial at work here, either in the lovers’ determined tantric exhibitionism, or the non-lovers, non-erotic erotics. Yet, as they slide once more into each other, until the black-haired girl is lying across the red-haired kid’s lap, and he doesn’t so much grab as guide her ass, with the palm again, deliberately flattened against the curve of thigh and cheek, until her legs curl into him, and her shirt rides up to reveal a naked back he will never touch, although it is the touch we are all waiting for, as, instead, she reaches up to cup his face in both hands and pull him down into a kiss, soundless this whole time, it is difficult to know how much of this is, in fact, performance, staging, whatever you want to call it, and what feelings or other unintentional stirrings we’re also witness to.

“I hope they like each other,” someone says behind me.

“They’ll like each other by the end,” says another.

“They’d better, or there won’t be a repeat.” says the first.

We get away from the commenters and walk around the couple, whose kiss now seems to aspire to Rodinesque duration as well as composition, towards the great white ramp, heading up. All walking in the Guggenheim is walking around. Before we mount, I steal another look at the lovers to see if they still have their clothes on. At the top of the first level, an elfin-looking child who we later realize reminds us of Haley Joel Osmont in AI, as much for his voice as for his perfectly unwasted motion, runs up to us and introduces himself cheerfully.

“I’m Finn.”

We introduce ourselves and shake hands. He looks a little surprised, as though our names should be irrelevant, and stumbles for a beat.

“This is a work by Tino Sehgal,” he says, “Will you follow me?”

“With pleasure.”

He runs up some steps into an empty, clam-shaped gallery recessed from the ramp. He takes up a position ahead of us, leaning against one of the arch’s bases.

“Can I ask you a question?” he asks.

“Sure.”

“What is Progress?”

And so it begins, our progress through progress, up each stage of the long ramp.

“It’s the 64 billion dollar question.” I say, smiling and wondering where my mind dredges up the cliches used on me by older generations. Has anyone my age or younger even seen the “64 Thousand dollar question?” It’s 12.30 on Sunday morning and I’m hung over and a little sleepy, not in a mood to ponder the imponderables with a middle-schooler.

“There’s no wrong answer,” Finn says, cheerily, looking up at me with beatific blue eyes as I mull over my response a little too long for his liking.

“Well, some people say progress is only the progress of technology. Like going to the moon is progress.” It seems easier to start there, with something I can’t possibly believe. He seems almost satisfied with this, but begins darting up the ramp, sprite-like, eager to get somewhere, and we follow him up.

“Progress is when we’re able to look back at the ruins of our own efforts,” my companion says, as we reach the bend and columns marking the empty museum’s next level. A young woman or older girl, in jeans, t-shirt and vest, comes out from somewhere and meets us on the ramp. “This is Abby,” Finn says, to us, then, to her, as if imparting a lesson: “I’ve learned that progress is technology, or transportation, or…regarding the failures of others…”

“Um, reaching a point where you regard your own efforts as ruins.”

“Right!” Finn glides away behind the column, offstage, and Abby takes a firm, contentious tone.

“Progress is failure? really?”

“Progress is the recognition of failure.” My companion says. She’s from a former Communist country and has a taste, born of experience, for such dialectical paradoxes.

Things discussed as Abby takes us up the next two rotations of the ramp: the poet Yeats’s theory of history as cyclical repetitions, a systole and diastole of interwoven order and disorder, represented by two cones, nested within each other, which he calls gyres, the resemblance of the Guggenheim to a gyre, whether you need a sense of an ending to have progress, or whether, like the Aztecs, a belief in one’s own civilizational doom brings about the inevitable sooner rather than later, whether the American idea of progress without end is sustainable.

I’ve had this conversation before, at other times, spontaneously, or in classrooms. Suffice to say that the question interests me but I haven’t made up my mind about it. I’m not about to start walking backwards, pretending to be Walter Benjamin’s “angel of history,” although I’m tempted. I realize we’re bound to go around in circles here, even if the circles are concentric and mounting towards some end point. Progress is time, which does not go backward, at least for individual human lives. I want to talk about the museum stripped of its paintings, its sculptures, turned into the performance space we now are part of.

Abby hands us off to another woman, with the maturer phrase “we were talking about…” Dressed in sleek business suit, sensible flats but adorned with a glittering silver necklace, she takes up our musings on the museum’s nakedness. “You know,” she says, “when the colonists came to America and they saw these naked Indians, they thought they couldn’t possibly be human beings because they didn’t have clothes…”

“So is a naked museum still a museum? Is that where we’re going?” I think, without saying anything aloud, it seems pointless to say too much aloud, for I’ve also just realized what’s going on here: we’re progressing through the ages of man, or woman! Our guides keep getting older. Maybe I say this or something like this, because our guide or interlocutor is now talking about the problem of representing time in art and in space.

I look over the side, momentarily distracted, in the eye of the vortex, the couple are still visible, still at their unending foreplay, still dressed, always, always shall they kiss, at least in this space. There are some kinds of progress, but the living Grecian urn is just as much a progress of substitution as an “advancement.”

Nearing the top now, with only a twist and a half to go, we are met by a vigorous, silvery-haired woman with tortoise-shell reading glasses and a warm, knowing smile. Again we introduce ourselves, but she actually takes this in and asks what we do. This conversation feels more like something one might have at an actual party, and this woman tells us her “real” occupation and then tells us she’s not supposed to tell us that. It’s the first of many “asides” she’ll make, as she also engages my companion in a discussion of architecture and the possibility of making a giant skateboarding ramp of the Guggenheim. We climb towards the visible and promised end, our steps slow and heavy as the movement of the couple below as though we want to stretch out the time. We contrive ways to pause her, to get her to tell us stories about other people she’s talked to on the way. I linger at the edge, peering down into the vertig

inous abyss, watching other groups make their literal “progress” along the ramp, feeling like some character inside a medieval painting of heaven or hell, or part of a democratic “mass ornament” that is simultaneously an “individualist” ornament, which still allows individuals to become distinct, even as, from above, we see them all “individualizing” in similar ways. We watch a woman in a wheelchair pushing herself up the ramp with powerful strokes of her muscled arms meeting her adult guide, a woman we’ll later learn is Guggenheim curator Nancy Spector, taking her regular shift just like the rest.

“Have there been any catastrophic incidents?” I ask, “anyone standing in the way of progress?”

“Not so far,” our latest and last Virgil says, “the walking seems to keep people pretty focused and in a good mood. But I really shouldn’t be telling you this. I’ll get a reprimand,” she grins wickedly, the merry transgressor. It’s hard to know at this point whether this, too, isn’t part of the performance, that we’ve progressed to the “meta” level, the conversation about conversation, the moment when the illusion begins to crack and reveal itself as an illusion, as performance, Prospero laying down his staff, or if this has been the inexorable but personal path of our own “enlightenment,” our progress. At the top, there’s a sadness in letting go, in saying goodbye, as when you’ve been through a particularly good session with a psychoanalyst and you realize that you cannot keep this person talking to you for hours, that there’s a routine, a system, that you will see her disappear down the firestairs “staff only” exit and reemerge, a few tiers down, at her station, ready to lead another group up the path.

Later, lingering at the top, we run into a friend who’s involved in the show. She reports one of the guests saying to her, “So you too will abandon me,” whether in half-facetious flirtation or genuine reproach, we’ll never know. As much as Tino Sehgal has managed to stage a classically harmonious meditation on the various senses of progress, his work also produces situations like these, for as much as it is a work of highly “conceptual art,” it is also theater and so comes under the psychological conventions of theater.

It’s unclear, in fact, whether the performance succeeds more as theater than as intellectual discussion. The accidental questions and observations that came to mind as we walked through mattered as much the enframing “theme” of enlightenment, or progress. “The blocking is great!” I thought, when Finn hopped up onto the impromptu proscenium, while also wondering how I talk to children, teens, equal grownups, and older adults. What would have happened if a few of the grownups were not as well-dressed as the others? What if some actually looked like homeless people? What if some had disturbing scars? What do all those French tourists make of it? Do they recognize the gallery of New Yorker types each of these ages also represent: the precocious child, the “know-it-all” teen, the busy, successful career woman, the witty and wise elders of the tribe? This catalog of “urbane” types is unchanged since Plato first began to blur the distinctions between theater, philosophy, and art, dialogue and dialectic.

A problem for Tino Sehgal as much as it was a problem for Plato is that performed conversation is still performance as much as it’s conversation. It’s one thing to perceive the stark whiteness and vertiginous openness of the Guggenheim as an ideal contemporary representation of the Athenian “agora,” and another to allow “the art of conversation” to take place unimpeded. Socrates and friends had the world all before them, at least until the master’s trial and death. The outcome of the historical Socrates’s actual dialogues were uncertain, but Plato’s readers are always being driven, guided, taken in hand, “You are quite right, Socrates!” A too-close simulation of the real thing, as with the aestheticized foreplay between the “living sculptures” in the atrium, tends to haunt us with a sense of the gap between real and representation, in a way, for instance, that going to theater does not, where the barrier of the stage curiously liberates our emotions as it keeps our self-regarding anxieties at a remove. With the barrier gone, we risk getting bogged down in an existential quagmire wondering whether all sex isn’t “simulated sex” or all conversation isn’t simply a series of “theatrical” gestures meant to showcase something different from the actual words used, solving a problem by means of our own rhetorical power instead of through mutual investigation and open-ended exploration.

Artists over the last three decades, borrowing from theater and even, increasingly, from literature, have plunged eagerly into the deconstruction and disassembling of the barriers between spectator and work, as well as the barriers between “Art” and other Arts. Going to a museum of contemporary art is now a bit like being present at a tacit contest in which “the art world” attempts to do everything but what was once called “art,” in order to assert its continued dominion over all the arts. Sometimes, however, the barriers vengefully reassert themselves, in unexpected ways. What happens when dialogue is framed within a place meant to house the finished works of the past and an 18 dollar admission fee? The historical pessimist does not see this as an unequivocal liberation of the museum. Rather, it appears as the museumification of a form of life once engaged in outside the museum—one more disturbing sign of a decline of that form. The fascination exerted by Tino Sehgal’s piece shares something with the interest in glacier tourism and the growing rage for exhibitions of books as “objects” to be observed rather than read. On certain days, at certain hours, one’s guide through the last stage of progress might even be the author of a recent book on the history of conversation. And yet, Sehgal’s fidelity to certain classical harmonies, a real German tradition of engagement, enlightenment, and Romantic dialogue, even amidst the most extreme avant-gardism, shows that old forms of art and ways of life sometimes retreat into museums to grow again in the minds of those who’ve witnessed it. One day, we may all have world enough and time for an ongoing inter-generational conversation about the meaning of progress. For now, you can get a good simulation of one, but only for six more days.

The tropes of '80s commercials

Last night after slogging through The Accidental Tourist*, the latest in John’s losing streak of movie picks (he’s seriously some kind of mad savant when it comes to finding films with good pedigrees that are nonetheless god-awful; see After Hours and They All Laughed), we watched a bunch of ’80s commercials on YouTube, which was endlessly entertaining. After watching close to a hundred commercials from any given era, you really start to see some patterns. Here were the big ones:

- The “Balanced Breakfast”: So we’re all familiar with the cliche of the balanced breakfast. The weird thing, the thing I didn’t remember, is that the balanced breakfast, no matter the cereal, always looks exactly the same: two slices of toast with butter, a big glass of milk and a big glass of orange juice. Sometimes it’s real toast, sometimes it’s cartoon toast, but there’s always the toast and the multiple beverages. What the hell? Wouldn’t you expect the balanced breakfast to include, like, fruit or something? Or an egg? Why would anyone eat a bowl of cereal and then, to balance it, add more processed wheat and another pint of milk? In the late ’80s, when fiber became all the rage, the toast became two bran muffins in some instances.

- Businessmen: There are only a few kinds of males in ’80s commercials: adorable/annoying kids, aggressively blue-collar guys with accents (see the Liquid Plumber commercial where they repeatedly compare the “thin stuff” and the “thick stuff”), and businessmen. The vast majority of males in commercials were businessmen. Businessmen eating cereal, businessmen drinking coffee, businessmen taking Pepto Bismal, businessmen lifting their arms to prove they wear Sure/use Dial, etc. (Women, on the other hand, are either sensible housewives, high-power secretaries, or out of your league.)

- Gum Makes You Cool: Chewing bubble gum, putting gum in your mouth (especially in such a way that the stick folds in half visibly as you push it against your tongue), popping a big bubble on your face, stretching your gum out in a tether between your teeth and your fingers (the epitome of cool, I thought, when I was a kid): these activities all signal that you are awesome and having an awesome time. (My old friend Marisa has a distinct memory of putting her hair up in a side ponytail, checking herself out in the mirror approvingly, and thinking, “I need some gum.”)

- White People: Everything was marketed at white people in the ’80s. Especially notably, McDonald’s and other fast-food joints (Wendy’s and Burger King were big) were all trying to appeal to a higher tax bracket than they do now. The only commercials we saw with black actors were for laundry detergent/fabric softener, whatever that means.

- Gender Stereotypes: Evident throughout, of course (this hasn’t changed), I was especially appalled by the kids’ toys. The stuff for boys was SO FREAKING VIOLENT. It’s like, aircraft carriers that unfold into missile silos that transform into nuclear warfare. WTF?! Toy company executives should be taken out and shot by the bloodthirsty Republicans they’ve created. Girl toys, of course, are sickeningly domestic and thoroughly pink. Barbie’s furniture is all pink. Who buys a pink dining room table, I ask you? I noticed that board games, on the other hand, are always depicted in play by both a boy and a girl (if not a whole family). Why is it that only board games are gender-neutral?

- Nightlife: The mid-80s-era commercials for Michelob, to which the night belongs: so hot, right? Singles’ night out in New York. When I saw these as a kid I couldn’t wait to be a grown-up. The aesthetics remind me of the video for George Michael’s “Father Figure” (my favorite karaoke number, FYI). See both below.

White Columns -- Archive in Progress

Invitation for Gordon Matta-Clark’s ‘Open House’, May 1972, 112 Greene Street

White Columns is pleased to introduce its ARCHIVE IN PROGRESS. ARCHIVE IN PROGRESS reflects the rich archival holdings relating to over forty years of programming at White Columns and 112 Workshop /112 Greene Street. This online resource was developed as a way to make historical documents including exhibition materials, invitations, posters, flyers, reviews, out-of-print publications, un-published images and other materials accessible to the broader public.

ARCHIVE IN PROGRESS will continue to be augmented and will hopefully become as comprehensive as possible in reflecting White Columns’ and 112 Greene Street’s history.

Please feel free to browse the archive at: www.whitecolumns.org/archive.

If you are in possession of any materials relating to White Columns’ or 112 Greene Street’s history and would be interested to include them in the ARCHIVE IN PROGRESS – please contact us at info@whitecolumns.org. WWW.WHITECOLUMNS.ORG

Groover's paradise

If the Armadillo World Headquarters was the heart of Austin’s music community in the early Seventies, Soap Creek Saloon was its soul. The rundown shack of a venue was on what was then a godforsaken stretch of Bee Caves Road, and the rutted dirt trail that led to it was even more notorious. You’d never know it today, looking at the strip malls that line the highway, but it was the scene of many a wild night.

Owners George and Carlyne Majewski doubled as manager and booker, respectively, of the club called “Home of the Stars” as Kerry Awn’s posters proclaimed. Austin traditions like the Uranium Savagesi Spamarama, and the George Majewski Lookalike Contest began at Soap Creek, which was roughly the size of two Continental clubs shaped as an “L.”

The best memories come as faces and images. Bartenders Lydia, Cecil, and Vennell. A Texas-size doorman named Billy Bob Sanders. The pool tables with Alvin Crow and cartoonist Jaxon hunkered down over pool tables as Austin Sun staffers Bigboy Medlin, Michael Ventura, and Jeff Nightbyrd looked on. The jukebox with Roky Erickson and Cookie & the Cupcakes filed side by side. Posters of past and future gigs lining the rough wood walls in the smoky haze. The Royal Hawaiian Prince in full regalia, sitting on the couch with terminally sagging springs.

Softball games, birthday parties, wedding receptions (mine), and a ready-made location for movies (Outlaw Blues). Sporadically, someone like Barbara Trout would open the kitchen for nachos, chips and salsa, and other treats suited to the munchie-ridden audience. And if Big Rikke, the Guacamole Queen, was in the ladies’ room line, you didn’t dare cut in front of her no matter how bad you had to pee. No backstage, only a grassy area outside with bad lighting, perfect for between-set smoking, powdering your nose, or stealing kisses.

We drank Pearl, Lone Star, plain ol' Shiner before there was Bock, and 50-cent tequila when Paul Ray & the Cobras played on Tuesdays; Soap Creek was as crucial to Stevie Ray Vaughan's career as Antone's or the Rome Inn. Country was at its best in those days with Greezy Wheels, the Lost Gonzo Band, Marcia Ball's Freda & the Firedogs, Plum Nelly, Augie Meyers & the Western Head Band, and Alvin Crow & the Pleasant Valley Boys.

Steam Heat and Storm were big weekend draws, and the club cultivated the Lubbock mafia of Joe Ely, Butch Hancock, Jesse Taylor, and the usual suspects. Clifton Chenier and Link Davis made their ways from Louisiana to hold down weekend gigs. Until 1974, the closing time was midnight weeknights and 1am Saturdays. Doug Sahm lived in a house across the parking lot and down the road, hidden by trees and foliage, but close enough for his kids to charge people for “parking.”

That was another thing about Soap Creek. It raised a generation of kids, many of whom grew up to be musicians. Shawn and Shandon Sahm, Ian Moore, and the Sexton brothers knew all about stretching out on metal chairs by the tables in the far corner. The Majewskis even raised son Ross and daughter Keri Lynn by the club’s neon lights.

What Soap Creek was best for was dancing. Men in the Seventies still knew old-school couples dancing or could two-step, both of which better suited the music than the freeform calisthenics that passed for dancing in the Sixties. Paul Ray was almost single-handedly responsible for keeping slow dancing alive in Austin when “The Hustle” ruled discos. In 1975, I turned 21 at Soap Creek, dancing the night away.

Soap Creek wasn’t the first victim of local suburban development, but a harbinger of club fates to come when it moved to town in the late Seventies. Like Antone’s, which also relocated to the north side for a time, the venue tried its luck at the old Skyline Club on North Lamar. The Skyline had a venerable history as a country music venue — Hank Williams played his last gig there — so the move worked. For a while.

Parts of Honeysuckle Rose were filmed at the North Lamar incarnation, booking policies expanding to include the burgeoning sounds of punk and New Wave, but progress got the better of that location as well. By 1980, Soap Creek was trying its luck for a third time on South Congress at Academy, where apartments stand today. That worked too. For a while.

The South Congress site continued hosting Spamarama, Savages gigs, benefits, birthdays, and bachelor parties (mine, or rather, Rollo’s). It was a good foil to the Continental Club and the nearby Austex Lounge, forming what we jokingly called the “South Austin triple crown.” Nevertheless, George and Carlyne opted to give it up and sold it in the mid-Eighties. Soap Creek flowed lightly through a couple more years and dried up forever in 1985.

When old-timers wax nostalgic about Soap Creek, you can bet they’re remembering that first location on Bee Caves Road. It wasn’t that those days were more innocent — in many ways the Seventies were just the calm after the Sixties storm — but the Austin of that era had a charm and sense of community that’s revered by many but largely missing today. The reunion poster by Soap Creek artist-in-residence Kerry Awn has the likeness of Doug Sahm with the word “Coach” underneath, an appropriate way to recall the man whose many talents personified Soap Creek’s eclectic musical offerings.

Awn’s poster also resembles the cover for Sahm’s Groover’s Paradise album, his quintessential valentine to Austin. Sahm extols our town’s virtues in the song, but there’s no question what he’s singing about are the wasted days and wasted nights of Soap Creek Saloon in the Austin he so loved.

Offshore/Elsewhere

No one has yet offered a definition of ‘tax haven’ on which we can all agree. The IMF, the OECD and the other main agencies tend to adopt the language they think acceptable to their own constituency. The term ‘tax haven’ is too obviously value laden, as the French equivalent, paradis fiscal, makes clear. ‘Offshore’, too, conjures images of island paradises, when some of the locations involved – Liechtenstein, for example – are landlocked. ‘International financial centre’, a creation of the financial services industry, seems designed solely to give an air of respectability.

There are four primary uses for ‘tax haven’ locations. First, they are used by those wishing to avoid or evade their obligation to pay tax. Tax avoidance is legal, but contrary to the spirit of taxation law, while tax evasion is always illegal, involving the non-disclosure of a source of income to an authority that has a legal right to know about it.

Second, they are used to hide criminal activities from view. That criminal activity might be tax evasion itself, but might also be money-laundering or crimes generating cash that needs to be laundered – theft, fraud, corruption, insider dealing, piracy, financing of terrorism, drug trafficking, human trafficking, counterfeiting, bribery and extortion.

Third, they are used by those who want their activities to be anonymous, even if they are entirely legitimate. Some people wish to hide their wealth from their spouses, for example; others might want to conduct trade which, though legitimate, might risk their reputation.

Fourth, they are used by those seeking somewhere cheaper to do business; in these locations they can usually avoid the costly obligation to comply with regulations that would apply onshore.

The need for anonymity is common to all these activities, which take place in what one might call the ‘secrecy world’. Secrecy is a property right like any other. To create and protect it requires the rule of law. Governments that choose to create laws allowing it to exist must have status as international jurisdictions (though not necessarily as countries, as the British Crown Dependencies demonstrate). Since no jurisdiction willingly undermines its own laws, the secrecy so created can be used only by people residing outside its own domain. The regulations created by these ‘secrecy jurisdictions’ are designed to undermine the legislation or regulations of another jurisdiction. To facilitate matters, a legally backed veil of secrecy ensures that those making use of them cannot be identified as doing so.

Secrecy jurisdictions raise revenue by collecting fees from registering companies. They may also charge fees for regulating the financial services industry located in their domain, and collect tax on the personal earnings of anyone working in that industry…

All this is possible because secrecy jurisdictions create the structures that the financial services industry sells access to. Typical among these are tax haven companies. These are extremely secretive: no information about them is made available on any public register, and very often the local tax authorities know nothing about them either. Yet even that level of secrecy tends to be insufficient for those engaged in offshore activities. The tax haven companies are almost invariably owned by trusts, which are also registered offshore and are run by the local financial services industry through specialist companies. The trusts are completely anonymous: there is no record of them on any public register; they are not taxed locally and local tax authorities know nothing about them. The person creating them is not identified in the trust documentation, which never specifies who the beneficiaries are. An offshore company owned by an offshore trust presents an almost impenetrable barrier to inquiry, equivalent to the banking secrecy offered in a country like Switzerland, not least to law enforcement agencies and tax authorities around the world – hence the reputation offshore has for assisting crime.

The bankers, lawyers and accountants who operate from these jurisdictions provide ‘secrecy services’ to their clients. These ‘secrecy providers’ may call themselves ‘offshore finance centres’ or ‘international finance centres’, but that is misleading. Secrecy is what they are selling.

The customers for secrecy services will never be found in the jurisdiction in which their provider is located. They are always located ‘elsewhere’ – that is, outside the secrecy jurisdiction’s domain. ‘Elsewhere’ is, in many ways, a more appropriate term than ‘offshore’. It allows secrecy jurisdictions, secrecy providers and their customers to maintain the claim that they are conducting legitimate, well-regulated activities, because the substance of the transactions arranged by secrecy providers always takes place ‘elsewhere’. Regulatory compliance within the secrecy jurisdiction is, as a result, easy to engineer, because nothing happens there, but transactions undertaken ‘elsewhere’ will also escape regulation in the jurisdiction where the activity is actually taking place. That of course is the intention.

Secrecy jurisdictions argue that because the transactions take place ‘elsewhere’, they are not taxable within the secrecy jurisdiction: such places choose not to tax transactions happening outside their domain. They then insist that declaring these transactions is the responsibility of their clients. That way the secrecy providers are able to argue that they are fully tax compliant.

We might think of this domain, in which the real transactions arranged by real secrecy providers take place, as the ‘secrecy space’. It is always ‘elsewhere’, and in that sense does not exist, but the willingness of secrecy providers, their clients, governments and authorities to behave as if it did creates the libertarian dream of an ungoverned domain for the making of unregulated profit. The truth is that multinational corporations do not really have offshore operations: they simply record some transactions in the secrecy space. George Osborne’s corporation tax reforms give the clearest possible indication that the Treasury has accepted the legitimacy of the secrecy space.

Matthew Carr

His sitters found Carr just as fascinating as he found them. Tall and painfully thin, despite an addiction to Cadbury’s Dairy Milk (economy size), his enormous eyes and shaggy hair made him look, according to a friend, “like a chewed toy lion”. The whole effect was rendered more extraordinary still by an eclectic wardrobe which might team harem pants and bright yellow vests with fox fur stoles and tiny sporrans — all carried off with raffish swagger.

Carr’s character, too, was a tangle of contradictions. He was, by turns, loyal and conspiratorial; tolerant and disapproving; emotional and impervious. He was once seen crying as he took his seat at a large sit-down dinner — because he had just read the name cards to either side of him. But on another occasion, when he was grossly insulted at a dinner party, prompting his friends to walk out in protest, they were somewhat taken aback to see, through a window from the street outside, Carr pouring a drink for his detractor and cackling with cheerful laughter.

As an artist, Carr’s standards were uncompromising, which was why he rejected oil paint as a distraction and concentrated on perfecting his drawings. He was always dissatisfied with what he had achieved, and perhaps it was the strain of not matching up to his own impossible perfectionism that contributed, during the middle part of his career, to a downward spiral of alcohol and drug addiction.

When he emerged into sobriety in the late 1990s, it was with a clear sense of what he had lost but also a determination to work on his own terms. He declined commissions in favour of choosing his own sitters, who included contemporary English writers and the semi-preserved dead in the catacombs at Palermo. These corpses, which Carr drew in 120 degree heat, were incorporated as individual drawings grouped within one large frame — a technique he applied to other subjects, including the stuffed monkeys and male genitalia.

The effect was to demonstrate that things which appear at first glance to be similar are in fact almost infinite in their variety. As Richard Dorment observed: “Once you overcome your initial hesitation, what is so striking is their curious humanity. It is the pathos of the monkeys’ existence and the indignity of their fate that we end up seeing. Long eyelashes, a soft moustache, and an open mouth make a desiccated corpse look as though it is asleep. And there is something sad and vulnerable about these clinical rows of blubbery paunches, flaccid penises and fat thighs, absolutely devoid of any sexual or procreative connotations.”

An introduction to "Paprika"

Paprika, the movie we’re about to see, is based on a fictional technology that allows people to share a dream. In fact, though, such a technology does exist. Several such technologies do: A poem can share a dream. A novel can sustain the sharing of one for weeks or even months. Movies may be the most vivid means of dream-sharing. Their power is acknowledged every time a timid viewer like me says, of a particularly gory or scary-looking one, that he can’t go see it because it would give him nightmares.

Suspend your belief in poems, novels, and movies for a moment, however, and imagine that dream-sharing is something completely new in the world. How will society react? Will people use the technology to reach a new understanding of themselves, extending the insights of psychoanalysis and philosophy? Such a development would require a great deal of attention to people as individuals. It would probably be easier and more profitable to use the new technology for entertainment. A dream that flatters or pleases dreamers could be mass-distributed. Corporations could hire its distributors to spike it with appetites for products; governments could pay for inducements to passivity or simply for distractions that camouflage what is happening to citizens in the real world. Plato would almost certainly have banned dream sharing from his republic.

In animated movies, and in live-action movies enhanced by computer graphics, the few constraints that everyday physics once imposed on moviemaking are overcome. The takeover of animation by computers, in the last few decades, may have intensified anxieties. What is the fate of creativity in an electronic age? Will it be the handmaiden of liberation or slavery? Like all great artists, Satoshi Kon, the director of Paprika, seems to have harbored a certain ambivalence about his chosen medium. Though computers have made it possible to automate much animation, Kon liked to draw storyboards for his movies himself, by hand, and in none of his movies did he shrink from challenging the conventions of the genre.

Kon seems, in fact, to have seen himself as a little bit at war with the conventions of mass-produced Japanese animation, making them the butt of a joke in the first scene of the first movie he directed. Kon’s Perfect Blue, released in 1997, begins with an action sequence by costumed superheroes, set to blaring, triumphant music, but the superheroes are almost immediately revealed to be no more than the mediocre opening act at a rinky-dink outdoor theater. (The joke is reminiscent of the melodramatic action-movie “conclusion” that begins Preston Sturges’s Sullivan’s Travels.) Perfect Blue is really about the next act at that rinky-dink theater, an all-girl pop group, and in particular, about the identity crisis that the group’s lead singer suffers as she transforms herself from an inoffensive teen idol into an actress with roles that are emotionally painful and sexually mature. Kon imagines the young actress being haunted by her pink-tutu-wearing younger self, and it soon becomes difficult for the viewer to distinguish between the actress’s real-world agonies and the imaginary ones that she is portraying in her first movie, whose title is, tellingly, “Double Bind.” The transitions between reality and fantasy are dizzying. “The real life images and the virtual images come and go quickly,” Kon explained in an interview.

When you are watching the film, you sometimes feel like losing yourself, in whichever world you are watching, real or virtual. But after going back and forth between the real world and the virtual world, you eventually find your own identity through your own powers. Nobody can help you do this. You are ultimately the only person who can truly find a place where you know you belong.

In Kon’s second feature film, Millennium Actress, released in 2002, he explored a similar confusion, this time by imagining a documentary about an elderly actress who can no longer tell the difference between memories of her life and memories of the movie roles she played. Her love story hopscotches through a century of Japanese film history and several centuries of Japanese history simultaneously. In his third film, Tokyo Godfathers, released in 2003, he defied convention in his choice of subject matter: three homeless people—an alcoholic man, a transvestite, and a runaway teenage girl—find an abandoned baby while rummaging through garbage on Christmas. Trying to do the right thing by the baby, each character must re-examine a melodramatic fantasy that has taken the place of his true life story.

Paprika, released in 2006, reprises these themes: doubles, the misapprehension of the past, the risk of sexuality, the confusion between reality and fantasy. Kon imagines his movie’s dream-sharing technology as a small, bent, white wand, shaped like a question mark or a miniature shepherd’s crook, with articulated teeth, the size of grains of rice, that glow a soothing robin’s egg blue. The DC Mini, as it’s called, is cute and menacing at the same time, like the many handheld devices that one nowadays sees people plugged into on the subway. Its inventor is a childish, absurdly overweight man named Dr. Tokita, whose talent everyone envies. The pioneer in its therapeutic use, however, is a stylish black-haired research psychologist named Dr. Atsuko Chiba, who, since the technology is not yet legal, treats patients only while disguised as red-haired, freckled girl named Paprika.

In the movie Inception, which some of you may have seen, there are clear rules about the mechanics of entering dreams. In Paprika, there aren’t. There is a mechanism for awakening dreamers, but its function isn’t certain. One can never be certain whose dream one is in; in fact, control of a dream may change from moment to moment. The conceit of Inception is that it takes great cunning and much effort to implant an alien idea into someone’s mind. In Paprika, such an implantation is distressingly easy. The difficult thing is to learn through dreams how to become oneself.

Be patient, Paprika several times advises one of her subjects. Much of the movie is devoted to the interpretation of a single dream, with an attention to detail and a willingness to defer understanding that Freud would not have been ashamed of. But not all the dreams in the movie prove susceptible to analysis. In a particularly dangerous one, we seem to see capitalism run amok—commodities themselves on the march, as if toward an Armageddon or a coronation. The philosopher Martin Buber once warned of “the despotism of the proliferating It under which the I, more and more impotent, is still dreaming that it is in command.” Will this someday be humanity’s only dream?

Kon died of pancreatic cancer in August 2010 at the age of forty-six. A posthumously posted letter to fans suggested that he had completed storyboards for The Dreaming Machine, a children’s movie that may be released later this year

. One suspects, though, that Paprika is his masterpiece, and his early death makes more poignant the rich dream at the movie’s start, in which one hears the slowing clicks of a movie projector that has come too soon to the end of its reel.

Thanks to all of you for coming out to see the movie, and thanks to Tim McHenry and Brendan Hadcock of the Rubin Museum of Art for inviting me and for arranging the screening. Enjoy the greatest showtime.

Chesterton on lying in bed

I remember having a conversation a couple of days ago about the bases on which people are likely to discriminate against others in the future. My view is that they’re likely to find something. Chesterton’s essay “On lying in bed“ captures the dynamic I had in mind quite well (I have very little sympathy with C’s politics but much more with his attitude toward the future — I share his dislike of fastidiousness about little things while also extending this dislike to fastidiousness about big things):

The tone now commonly taken toward the practice of lying in bed is hypocritical and unhealthy. Of all the marks of modernity that seem to mean a kind of decadence, there is none more menacing and dangerous that the exaltation of very small and secondary matters of conduct at the expense of very great and primary ones, at the expense of eternal ties and tragic human morality. If there is one thing worse that the modern weakening of major morals, it is the modern strengthening of minor morals. Thus it is considered more withering to accuse a man of bad taste than of bad ethics. […] Especially this is so in matters of hygiene; notably such matters as lying in bed. Instead of being regarded, as it ought to be, as a matter of personal convenience and adjustment, it has come to be regarded by many as if it were a part of essential morals to get up early in the morning. It is upon the whole part of practical wisdom; but there is nothing good about it or bad about its opposite.

Misers get up early in the morning; and burglars, I am informed, get up the night before.

Ferdinando Scarfiotti and "Toys"

“Scarfiotti returned to work in 1990 on Barry Levinson’s Toys. This project dated from 1978, its fanciful story (of a bombastic general and his holy fool of a nephew who feud over the family toy factory) having found little favour or funding before Levinson’s later triumphs. Toys plainly required a strong and guiding design concept, and Levinson went after the best man: what he got in return, over their first breakfast meeting, was Dada. ‘When I read the script,’ Scarfiotti claimed, ‘I told Barry I would do it if he’d allow me to stay away from traditional American fantasy – such as the Disneyland themes – and instead go back to the European modernist movement of the early century which included surrealism, dadaism and futurism’.

This was no idle threat, so to speak. Scarfiotti’s touchstone for Toys would be the Italian Futurist Fortunato Depero, a crackerjack of all trades whose inventions included patterned waistcoats, bolted books, sets for Diaghilev, and covers for Vanity Fair. The choice was inspired. Depero had also been a compulsive maker and illustrator of figurines, and, with Giacomo Balla, penned in 1915 Futurist Reconstruction of the Universe, hymning a new world order ‘run according to the principles of the Futurist toy’. M Depero’s joyful paeans to fighting dolls (not nearly so grimace-worthy as Marinetti’s conviction that war was a form of hygiene for civilisation) gave Scarfiotti a line straight into the highly coloured whimsy Toys required.

Scarfiotti was by now much perturbed by the industry’s changing perception of ‘visual style’. ‘If you look at what commercials and MTV are doing now, they’re so technologically advanced that it’s scary,’ he confessed. ‘But at one point all these new technologies become very unimaginative, and it gets very tiring for the eye and the mind to be bombarded with an enormous amount of images in a very short time’. Toys is therefore a clarion-call for the hand-made magnificence of which Scarfiotti was the master: the film came before its audience unarmed, with a child-like ingenuousness. ‘We have a tradition of whimsy here at Zevo Toys’, Leslie Zevo (Robin Williams) cautions his uncle Leland, sounding the keynote of the picture. In search of a unified concept for the Zevo Toys, Scarfiotti elected to shun the mass-produced and seek out the rare. ‘I decided that the old-fashioned wind-up toys . . . had a common look. They are very innocent and have a fantasy element to them, unlike the modern toys of today’. Thus Scarfiotti found himself realising what Depero only dreamed of, building a number of adorable toys with concealed war-waging capabilities.” [1]

“Scarfiotti conjures the innocence of the Zevo operation, and the subsequent threat to its purity, through boldly contrasting strokes. Initially Kenneth Zevo’s office is littered with wind-up toys, the walls awash in Depero’s carefree colourful frescoes; but upon his demise and the installation of brother Leland, military murals in gross parody of Russian Constructivism are painted over, and towering, threatening robots line the walls. As influential as Depero upon Scarfiotti’s internal logic was Magritte, who provided inspiration for mechanical wheezes (a pop-up house) and colour-schemes (several Zevo interiors are daubed after his inimitable skies). When required, somewhat to his distaste, to design a pop-video sequence, Scarfiotti appropriated Magritte’s enigmatic bowler-hatted mannequins, and in a barrage of cuts Robin Williams and Joan Cusack bring to life Golconda, Le Faux Miroir, and Le Mois des Vendunges, amongst others. There is even a canny homage to De Stijl, the design movement which gave a rational order to Futurism’s romantic, anarchic ‘machine aesthetic’. The Zevo factory’s canteen is a loving recreation of the classic Cine-Dancing room created by The Van Doesburg in 1928 for the Aubette entertainment complex in Strasbourg; coloured squares on stucco panels climb the walls in Van Doesburg’s dynamic, diagonal style of ‘Counter-Composition’.” [1]

“Scarfiotti celebrated his experiences on the film in terms which, for him, signified the highest praise: ‘Toys was the closest thing to theatre you can imagine. You start from a blank page and make a drawing, then a painting, and you have it reproduced on stage exactly the way you want’. His adventures in the cinema almost at an end, Scarfiotti had emphatically achieved something he had always sought. Paul Schrader, however, feels that Scarfiotti’s work on Toys was overshadowed by graver matters. ‘I think Scarfiotti was approaching an aesthetic crisis at the end of his career,’ Schrader reflects. ‘It’s a crisis not uncommon to exploratory, hugely influential artists. Nando had become so imitated towards the end of his life that it was harder and harder to work in his style without seeming to be derivative of the films which were derivative of him. I think if his health had been better, he could have attacked this dilemma frontally, gone back to work in Europe or done something more experimental. After The Sheltering Sky, health became an overriding concern. He didn’t want to be too far away from medical help and his friends. This meant maintaining a relatively expensive lifestyle, which meant big budget studio films. Toys can beseen as his attempt to reinvent himself: new palate, new tone, new shapes. A big budget Hollywood comedy is not the ideal place, to my mind, to reinvent yourself’.” [1]

ALL IMAGES AND ANIMATIONS TAKEN FROM THE BARRY LEVINSON FILM TOYS, 1992; ALL TEXT [1] BY RICHARD KELLY, TAKEN FROM “FERDINANDO SCARFIOTTI 1941-1994: EXCURSIONS INTO STYLE“ AS IT ORIGINALLY APPEARED IN CRITICAL QUARTERLY, VOL. 38, ISSUE 2, JUNE 1996