Search for ‘MATT ’ (136 articles found)

Among the Flutterers

When I listed the reasons homosexuals might be attracted to the Church and might want to become priests, I did not mention the most obvious one: you get to wear funny bright clothes; you get to dress up all the time in what are essentially women’s clothes. As part of the training to be an altar boy I had to learn, and still remember, what a priest puts on to say Mass: the amice, the alb, the girdle, the stole, the maniple and the chasuble. Watching them robing themselves was like watching Mary Queen of Scots getting ready for her execution.

Priests prance around in elaborately fashioned costumes. Bishops and cardinals have even more colourful vestments. This ‘overt behaviour’ on their part has to be examined carefully. Since it is part of the rule of the Church, part of the norm, it has to be emphasised that many of them do not dress up as a matter of choice. Indeed, the vestments in all their glory might make some of them wince. But others seem to enjoy it. Among those who seem to enjoy it is Ratzinger. Quattrocchi draws our attention to the amount of care, since his election, Ratzinger has taken with his accessories, wearing designer sunglasses, for example, or gold cufflinks, and different sorts of funny hats and a pair of red shoes from Prada that would take the eyes out of you. He has also been having fun with his robes. On Ash Wednesday 2006, for example, he wore a robe of ‘Valentino red’ – called after the fashion designer – with ‘showy gold embroidery’ and soon afterwards changed into a blue associated with another fashion designer, Renato Balestra. In March 2007, for a visit to the juvenile prison at Casal del Marno, he wore an extraordinary tea-rose-coloured costume.

Quattrocchi draws conclusions a little too easily from a consideration of the connection between the fury of the pope’s attacks on homosexuality and his attire. ‘The secularist,’ he writes,

will inevitably wonder, not particularly maliciously, whether such fury isn’t the fruit of a deeply repressed desire for what he condemns. Of an unconscious desire which manifests itself as its opposite … Now that he has ascended to the throne, our hero has discovered the dazzling clothes, the trappings of power and wealth, which centuries of pomp have draped on the shoulders of his predecessors. In this way, his true nature, his deepest unspoken inclinations are revealed. In short, he might simply be the most repressed, imploded gay in the world.

Quattrocchi also considers the relationship between the pope and his private secretary. The private secretary is called Georg Gaenswein. Gaenswein is remarkably handsome, a cross between George Clooney and Hugh Grant, but, in a way, more beautiful than either. In a radio interview Gaenswein described a day in his life and the life of Ratzinger, now that he is pope:

The pope’s day begins with the seven o’clock Mass, then he says prayers with his breviary, followed by a period of silent contemplation before our Lord. Then we have breakfast together, and so I begin the day’s work by going through the correspondence. Then I exchange ideas with the Holy Father, then I accompany him to the ‘Second Loggia’ for the private midday audiences. Then we have lunch together; after the meal we go for a little walk before taking a nap. In the afternoon I again take care of the correspondence. I take the most important stuff which needs his signature to the Holy Father.

When asked if he felt nervous in the presence of the Holy Father, Gaenswein replied that he sometimes did and added: ‘But it is also true that the fact of meeting each other and being together on a daily basis creates a sense of “familiarity”, which makes you feel less nervous. But obviously I know who the Holy Father is and so I know how to behave appropriately. There are always some situations, however, when the heart beats a little stronger than usual.’

In his book, Quattrocchi prints many photographs of the pope in his papal clothes, and many of Gaenswein looking sultry, like a film star, and a few of the two together, taking a walk or the younger man helping the older one to put on a robe or a hat.

Ty Segall in dreams

Last night, I went to see Ty Segall at Cake Shop and got more than I bargained for there. I showed up there late, with a humid drizzle going on as people poured out of the Lower East Side club strip for cig breaks and to socialize in a less cramped area, with taxis streaming by to pick up the floatsam and jetsam that would soon tire out. I made it downstairs in time to see the end of the set from the third band of the evening- it was almost perfect timing and even more amazing considering it was a four-band bill where I came for the last act.

People streamed out after the band finished and I made my way up to the front, near a fan mounted on the wall, which almost made it bearable to stand there near the end of the bar. I was squashed there with people trying to thread in near the stage or to order a drink but it seemed to be a decent perch. Ty and the band set up to go on soon but it seems like long time in there with the crowd and the heat. Though I was only ten feet from the stage, I couldn’t see anything except a tiny sliver of Ty’s face and occasionally a glimpse of his long hair manically bobbing up and down. Near the front of stage, some pretty weak moshing was going on but it didn’t matter since Ty was delivering- his set was good grungry garage rock which he’s now upped the ante with by adding a tuneful side to it on his new record Melted, which impressed me enough to come to out see him. Jay Ruttenberg, my friend from Time Out New York collared me and hung out there in front for a while but he couldn’t see squat either and retreated to back for some air. I did likewise and was ready to stay for a while until Ty tried out some tired jokes (“what didn’t the lifeguard rescue the hippie? He was too far out man!” and “What do you do if you see a space man? You park, man!”) and followed up his threat to play some Skynyrd by actually doing it (not “Freebird,” mind you) and a Sabbath cover. Not really into his bar band shtick and noticing that it was getting late (I have a day job, mind you), I took off and got home by midnight.

For the last few weeks, I’d been able to actually remember most of the dreams I had and when I’d share ‘em with my girlfriend or some bewildered friends who guest starred in them, they had no idea what it meant either or maybe just didn’t want to tell me that I’m just sick in the head.

But after Ty’s show, I had one that seemed to make things clear. Here’s the scenario. I’m at an outdoor amphitheater where the circus is performing. The seating looks crowded so I walk near a ground level opening where a few people are crowded around to see what’s happening. Even there, it’s hard to see anything. They bring a goat out and maybe other animals and everyone oooh’s and ah’s at it. I turn to look at the stands and I notice that there’s some clowns seated near the back with their props, including spray bottles. One of them nails me with water and at first I think it’s funny and then I realize that he’s trying to clear me from that area- the other people there have already left. I think of trying to walk in to find a seat but I look at my watch and notice that it’s getting late and that I should probably start heading home.

Oh, so it’s obvious, right? I was just processing in my mind what had actually happened to me a few hours ago (dunno who the clown was, maybe me). But it was such a relief and kind of a revelation to think that I could find some bearings about what was going on in my dreams and that I was kind of reliving scenes in my life. No, I probably can’t psychoanalyze your dreams and I’m obviously missing on a lot more going on but it really gave me some peace of mind.

And I to that I have Ty, a guy I could bare see, to thank for that…

From "Cezanne's Doubt," Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1945)

His painting was paradoxical: he was pursuing reality without giving up the sensuous surface, with no other guide than the immediate impression of nature, without following the contours, with no outline to enclose the color, with no perspectival or pictorial arrangement. This is what Bernard called Cezanne’s suicide: aiming for reality while denying himself the means to attain it. This is the reason for his difficulties and for the distortions one finds in his pictures between 1870 and 1890. Cups and saucers on a table seen from the side should be elliptical, but Cezanne paints the two ends of the ellipse swollen and expanded. The work table in his portrait of Gustave Geffroy stretches, contrary to the laws of perspective, into the lower part of picture. In giving up the outline Cezanne was abandoning himself to chaos of sensation, which would upset the objects and constantly suggest illusions, as, for example, the illusion we have when we move our heads that objects themselves are moving—if our judgment did not constantly set these appearances straight. According to Bernard, Cezanne “submerged his painting in ignorance and his mind in shadows.” But one cannot really judge his painting in this way except by closing one’s mind to half of what he said and one’s eyes to what he painted.

It is clear from his conversations with Emile Bernard that Cezanne was always seeking to avoid the ready-made alternatives suggested to him: sensation versus judgment; the painter who sees against the painter who thinks; nature versus composition; primitivism as opposed to tradition. “We have to develop an optics,” Cezanne said, “by which I mean a logical vision—that is, one with no element of the absurd.” “Are you speaking of our nature?” asked Bernard. Cezanne: “It has to do with both.” “But aren’t nature and art different?” “I want to make them the same. Art is a personal apperception, which I embody in sensations and which I ask the understanding to organize into a painting.”’ But even these formulas put too much emphasis on the ordinary notions of “sensitivity” or “sensations” and “understanding”—which is why Cezanne could not convince by his arguments and preferred to paint instead. Rather than apply to his work dichotomies more appropriate to those who sustain traditions than to those—philosophers or painters—who found them, we would do better to sensitize ourselves to his painting’s own, specific meaning, which is to challenge those dichotomies. Cezanne did not think he had to choose between feeling and thought, as if he were deciding between chaos and order. He did not want to separate the stable things which we see and the shifting way in which they appear. He wanted to depict matter as it takes on form, the birth of order through spontaneous organization. He makes a basic distinction not between “the senses” and “the understanding” but rather between the spontaneous organization of the things we perceive and the human organization of ideas and sciences. We see things; we agree about them; we are anchored in them; and it is with “nature” as our base that we construct our sciences. Cezanne wanted to paint this primordial world, and his pictures therefore seem to show nature pure, while photographs of the same landscapes suggest man’s works, conveniences, and imminent presence. Cezanne never wished to “paint like a savage.” He wanted to put intelligence, ideas, sciences, perspective, and tradition back in touch with the world of nature which they were intended to comprehend. He wished, as he said, to confront the sciences with the nature “from which they came.”

Why coffee stains are ring-shaped

There’s a group of clever people at the James Franck Institute (UChicago) who study some of the overlooked and bizarre regularities of everyday life — e.g. Tom Witten, Sid Nagel, Heinrich Jaeger, and Wendy Zhang. Their work has always struck me as very beautiful and “classical” in its spirit: it is the sort of thing the founders of the Royal Society, or for that matter Euler or the Bernoullis, might have studied and would have appreciated. They work on things like the flow of sand out of thin nozzles, the fact that liquids do not splash on top of Mt Everest, and the extent to which a droplet of water that pinches off a nozzle remembers the shape of the nozzle.

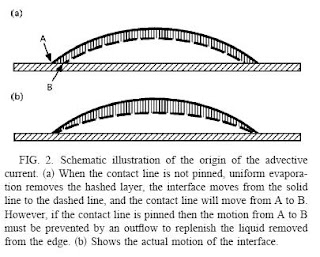

An esp. nice result that I heard about at a talk yesterday was Witten’s group’s theory of why coffee-stains have the sharp-edged, ring-like shapes they do. [The relevant references are Nature 389, 827 (1997) and Phys. Rev. E 62, 756 (2000).] The answer goes something like this: the edge of the coffee-bearing water droplet snags on surface roughnesses and gets pinned. (On sufficiently smooth surfaces, e.g. Teflon, coffee stains are not ring-shaped but uniform.) As water evaporates the bubble has to shrink; the water evaporates at roughly the same rate everywhere so ceteris paribus the bubble would want to shrink everywhere, but it can’t because that would decrease its diameter and require the edge to move, and the edge can’t move because it’s pinned. The only way to keep the edge where it is while all of the surface evaporates at the same rate is for fluid to flow from the center of the droplet to the edge, to replenish the water lost from the edge. So over time most of the water in the bubble evaporates from the edge, and most of the solute gets deposited at the edge, so the stain is ringlike.

Under certain conditions, the edge is “almost” pinned but periodically unsnags (“depins”), moves some distance, and then snags again; this leads to terrace-like stain patterns.

Food's Fiscal Facts, Marinetti, and the "Art of Eating"

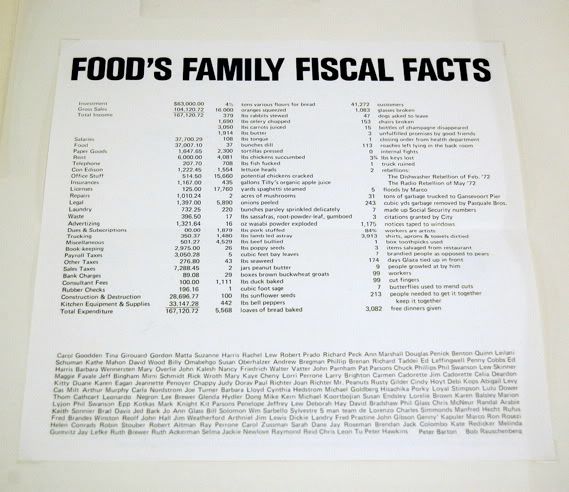

Food’s Fiscal Facts from Avalanche 4, 1972. Shown at “From the Archives: 40 Years / 40 Projects,” at White Columns, New York. Photo: 16 Miles [more]

Gordon Matta-Clark’s Food restaurant ran the advertisement above at the end of 1972, the first year of the restaurant’s operation. Favorite parts: 1,111 lbs of baked duck, 5,568 loaves of bread, 3,082 free dinners given, 1,083 glasses broken. They were paying $6,000 for a year’s worth of rent at the corner of Prince and Wooster in SoHo. (Lucky Jeans has the space today.)

On a related noted, I wrote a piece about art, food, and a few upcoming events in New York that combine the two. Here’s the opening, about Marinetti’s Futurist war on pasta:

“Pasta, however grateful to the palate, is an obsolete food,” Futurist leader Filippo Marinetti declared in 1931. “Its nutritive qualities are deceptive; it induces skepticism, sloth, and pessimism.” Despite generating considerable debate at the time, Marinetti, of course, lost his war against the Italian staple he claimed to despite photographic evidence that suggested his real feelings about the food were a bit more conflicted.

Confide in me, Tom

In his later years, comedian Groucho Marx became the unlikely penpal of poet T. S. Eliot, and the following is just one of many witty letters sent back and forth between the pair. Some background: previous to this one, Marx had started a letter informally with ‘Dear Tom, If this isn’t your first name, I’m in a hell of a fix! But I think I read somewhere that your first name is the same as Tom Gibbons‘, a prizefighter who once lived in St. Paul.’ to which Eliot replied, ‘I cannot recall the name of Tom Gibbons at present, but if he helps you to remember my name that is all right with me.’, hence the first half of this letter…

Dear Tom:

Since you are actually an early American, (I don’t mean that you are an old piece of furniture, but you are a fugitive from St. Louis), you should have heard of Tom Gibbons. For your edification, Tom Gibbons was a native of St. Paul, Minnesota, which is only a stone’s throw from Missouri. That is, if the stone is encased in a missile. Tom was, at one time, the light heavyweight champion of the world, and, although outweighed by twenty pounds by Jack Dempsey, he fought him to a standstill in Shelby, Montana.

The name Tom fits many things. There was once a famous Jewish actor named Thomashevsky. All male cats are named Tom — unless they have been fixed. In that case they are just neutral and, as the upheaval in Saigon has just proved, there is no place any more for neutrals.

There is an old nursery rhyme that begins “Tom, Tom, the piper’s son,” etc. The third President of the United States first name was Tom … in case you’ve forgotten Jefferson.

So, when I call you Tom, this means you are a mixture of heavyweight prizefighter, a male alley cat and the third President of the United States.

I have just finished my latest opus, “Memoirs of a Mangy Lover”. Most of it is autobiographical and very little of it is fiction. I doubt whether it will live through the ages, but if you are in a sexy mood the night you read it, it may stimulate you beyond recognition and rekindle memories that you haven’t recalled in years.

Sex, as an industry, is big business in this country, as it is in England. It’s something everyone is deeply interested in even if only theoretically. I suppose it’s always been this way, but I believe that in the old days it was discussed and practiced in a more surreptitious manner. However, the new school of writers have finally brought the bedroom and the lavatory out into the open for everyone to see. You can blame the whole thing on Havelock Ellis, Krafft-Ebing and Brill, Jung and Freud. (Now there’s a trio for you!) Plus, of course, the late Mr. Kinsey who, not satisfied with hearsay, trundled from house to house, sticking his nose in where angels have always feared to tread.

However I would be interested in reading your views on sex, so don’t hesitate. Confide in me, Tom. Though admittedly unreliable, I can be trusted with matters as important as that.

My best to you and Mrs. Tom

Summer political philosophy update

There are two different sorts of political disagreement among non-idiots — disagreements about the likely consequences of policies, and disagreements about values. In practice, people tend to conflate these, esp. where there isn’t an academic consensus, and adopt narratives that suggest that policies they disagree with would be disastrous regardless of values. This is usually, though not always, dishonest; few problems can be solved by dominance reasoning.

I’d describe myself as a left-wing individualist; I’m antagonistic in the abstract to most forms of communitarianism, unions, small-business-worship, homeschooling, extended families, nationalism, ethnic pride, segregation, etc. (And yes, from my perspective left-wing and right-wing communitarianism are similar phenomena.) On the other hand, I believe a fair bit of the negative communitarian case against modernity and modern liberalism: I’m not convinced that progress makes people happier; I agree with Naomi Klein (whom on the whole I dislike) that corporate interests corrupt politics, and that either politics must be insulated from big business or big business must somehow be shrunk (I’d prefer the former); I buy the conservative belief that diversity and urbanization spoils the sense of community and the real benefits that come with it (though I’d say, if so then fuck the sense of community). Etc.

I’m unsympathetic toward libertarianism largely because I don’t believe libertarian arguments. The value system, on the whole, I’m not that antagonistic towards. I’m in favor of wide personal freedoms, a moderately strong system of property rights — that is, I would like property rights to be strong enough that they are predictable, which is a pretty powerful constraint — and flexible employment. (On the other hand, flexible employment includes people with preexisting conditions; the current system, where some people simply can’t afford to lose their jobs, strikes me as intensely wrong. Similarly, I think that people in general ought to have the right to free speech de facto and not just de jure; one shouldn’t be liable to starve for protesting.) Lateral mobility seems at least as important as upward mobility, esp. assuming long lives and rapid technological change; I’m in favor of a reasonably strong safety net that allows people to change jobs in mid-career. And I just don’t think any of this is possible without big government and high taxes. I am quite strongly against outsourcing the safety net to families, charities, etc. because they’re bound to be discriminatory in ways I disapprove of.

I tend to distinguish between liberties that I consider valuable in themselves, e.g. the right to say almost anything you like with a reasonable shot at finding an audience, the right to a fair trial, the right to a decent education, etc., and those that are administratively useful, such as most property rights, the right to leave your money to your kids when you die, the right to read Joyce to your five-year-olds, etc. I don’t really have a problem with curbing the second kind of liberty if it serves any purpose and can be done predictably and systematically. (I’m a big fan of the rule of law: retroactive punishment, arbitrary seizure, etc. seem deeply wrong in themselves.) I approve of stuff like McCain-Feingold. Similarly, I don’t have a problem with laws mandating that private establishments can’t expel people for certain kinds of free speech, even if that seems somewhat anti-property rights.

I disagree with the linear-programming approach towards social policy, the notion that policies are best thought of as constrained optimization problems. The way I see it it’s only necessary for things to work well enough, or even not terribly, while satisfying as many constraints and desiderata as one wants to impose. Arguments that some policy change would make some system less efficient tend not to move me; the relevant question is whether they would make the system intolerably less efficient. I have a similar sort of attitude toward meritocratic objections to affirmative action (though for unrelated reasons I’m ambivalent about AA itself). If the govt forces companies to employ grossly unqualified people, or makes it impossible for e.g. whites/Asians to find reasonable employment or colleges, then that’s obviously a bad thing; if not, I don’t much care in principle if “The Best” people don’t get the best jobs. The exception to this is some areas in which there’s social utility to having a rat race because it makes people work extremely long hours, which leads to socially beneficial outcomes (e.g. research/some engineering jobs); in such cases, meritocracy provides the only sensible form of organization.

In general, I don’t find meritocracy (or its flip side, equality of opportunity) a useful concept. Opportunities are never going to be equal — even if the state ran education, some kids would get the best nannies — and in any case it’s not obvious that people with better genes deserve better outcomes. (The only argument for meritocracy I believe in has to do with encouraging hard work.) Some talent will inevitably be wasted; what matters from the point of view of progress is that meaningful opportunities should exist for people with exceptional abilities, and this condition is weaker and more enforceable than equality of opportunity.

I don’t think, however, that the current American educational and penal systems — by and large — offer meaningful opportunities even to talented poor kids in inner cities or Appalachia (never mind the third world etc.); the existence of an underclass of this kind seems to me a natural consequence of massive inequality, and also of the fact that there is, as of now, a de facto safety net for middle-class whites. If middle-class people were likelier to be locked up for trivial offences and suffered the same sorts of consequences as the urban poor habitually suffer — if enough suburban stoners ended up with AIDS — we might have a humane prison system. Similarly with busing and inner-city schools. The obstacle here is that it’s easier for the middle class to move out, insulate itself, and use its advantage in political clout to prevent busing; and the very poor end up trapped in ghettoes. I don’t see how it’s possible to address this sort of thing structurally without ensuring a more even distribution of wealth — though that is unlikely to be a sufficient condition.

One of the aspects of the communitarian critique that I find particularly interesting is the notion of the decline in the dignity of work — in pre-industrial societies, a higher proportion of jobs required skill or strength; the fashioning of worthwhile objects gave a meaning to one’s life, outside of consumption, that it is substantially harder to get out of a job at McDonald’s. (As Gregory Clark points out, it seems likely that the extent of structural unemployment — the fraction of the populace that hasn’t got the skills or the ability to do any kind of job that there is the demand for — will rise to a reasonable fraction of the populace.) This is a natural result of globalization — there is a market for only the best books, art, and (to some extent) science; both a small community and a large one naturally sustain roughly the same number of writers, and therefore a world splintered into disconnected islands would allow for a much greater fraction of the populace to take some pleasure in their skill. What the reader gains from having access to the best stuff being done is, however, enormous [though what does that mean? I don’t think it makes people objectively happier], and in the end I do believe in progress.

I started writing this down because I figured it would help me organize my thoughts; apparently it hasn’t. I’ll skip the bit about aesthetics for now.

Take "Dixieland" jazz

Take “Dixieland” jazz. Armstrong’s Hot 5 and Hot 7 sessions are perfectly listenable today. They still sound fresh and new. But any attempt to play in this style, by anyone after about 1940 who wasn’t part of the music in its day, is absolutely vile, in all cases, a priori and forever, categorically, amen.

While I don’t appreciate the hard bop of the “young lions,” I think it is still a legitimate style. Hard bop still doesn’t sound dated even today. Diana Krall, though she is not all that good in comparison with Ella, Sarah, Nancy, Dinah, etc… , can still be listenable at times, but the same problem of datedness applies. It’s not simply a matter of not being as good: there is a fundamental wrongness to the return to an ossified style.

Why can’t you write like Keats today? It is obvious that you can’t. It simply can’t be done. The results would be vile pastiche. Yet you can still read Keats fine… Why is Campion’s Latin verse, undoubtedly, lacking in aesthetic interest. It is the relation to the language itself that changes. Imagine an adept forger of Picasso, in 2030. If we like Picasso, wouldn’t it make sense to train people to make new cubist paintings, in that exact style? But almost everyone would agree that there is not point to that. Anything interesting that might come out of trying to paint like Picasso at a much later date would be in its radical difference from Picasso. This shows that what makes modern art valuable is its relation to its own time, its radical contemporaneity. And this applies to “modern” arts of the past two. Horace was his own contemporary. He is still a modern, so to present him in “modern dress,” to contemporanize him, is fundamentally misguided. There is no “past,” there are only other times that used to be the present.

What defines an epoch? What makes the past the past? What is “pastness”? Is it the sense of irrecuperability? Alienness? Datedness? It is us who define the past as such. In other words, the past is deictic.

"The Style is on the Inside"

Susan Sontag's essay "On Style" (Against Interpretation) contains many passages to warm an aging aesthete's heart. First, a selection:

Indeed, practically all metaphors for style amount to placing matter on the inside, style on the outside. It would be more to the point to reverse the metaphor. The matter, the subject, is on the outside; the style is on the inside. As Cocteau writes: "Decorative style has never existed. Style is the soul, and unfortunately with us the soul assumes the form of the body." Even if one were to define style as the manner of our appearing, this by no means necessarily entails an oppostion between a style that one assumes and one's "true" being. In fact, such a disjunction is extremely rare. In almost every case, our manner of appearing is our manner of being. The mask is the face. . . .

Most critics would agree that a work of art does not "contain" a certain amount of content (or function—as in the case or architecture) embellished by "style." But few address themselves to the positive consequences of what they seem to have agreed to. What is "content"? Or, more precisely, what is left of the notion of content when we have transcended the antithesis of style (or form) and content? Part of the answer lies in the fact that for a work of art to have "content" is, in itself, a rather special stylistic convention. The great task which remains to critical theory is to examine in detail the formal function of subject-matter. . . .

To treat works of art [as statements] is not wholly irrelevant. But it is, obviously, putting art to use—for such purposes as inquiring into the history of ideas, diagnosing contemporary culture, or creating social solidarity. Such a treatment has little to do with what actually happens when a person possessing some training and aesthetic sensibility looks at a work of art appropriately. A work of art encountered as a work of art is an experience, not a statement or an answer to a question. Art is not only about something; it is something. A work of art is a thing in the world, not just a text or commentary on the world. . . .

Inevitably, critics who regard works of art as statements will be wary of "style," even as they pay lip service to "imagination." All that imagination really means for them, anyway, is the supersensitive rendering of "reality." It is this "reality" snared by the work of art that they continue to focus on, rather than on the extent to which a work of art engages the mind in certain transformations. . . .

In the end, however, attitudes toward style cannot be reformed merely by appealing to the "appropriate" (as opposed to utilitarian) way of looking at works of art. The ambivalence toward style is not rooted in simple error—it would then be quite easy to uproot—but in a passion, the passion of an entire culture. This passion is to protect and defend values traditionally conceived of as lying "outside" art, namely truth and morality. but which remain in perpetual danger of being compromised by art. Behind the ambivalence toward style is, ultimately, the historic Western confusion about the relation between art and morality, the aesthetic and the ethical.

For the problem of art versus morality is a pseudo problem. The distinction itself is a trap; its continued plausibility rests on not putting the ethical into question, but only the aesthetic. To argue on these grounds at all, seeking to defend the autonomy of art. . .is already to grant something that should not be granted—namely, that there exist two independent sorts of response, the aesthetic and the ethical, which vie for our loyalty when we experience a work of art. As if during the experience one really had to choose between responsible and humane conduct, on the one hand, and the pleasurable stimulation of consciousness, on the other!

Much of Sontag's essay is concerned to break down the opposition between "style" and "content," but unlike others who sometimes complain about the persistence of this opposition but do so mostly in order to banish "style" from critical discussion altogether—it's just the writer's way of communicating his/her content—Sontag maintains it is content that should recede, becoming simply the word for a "special stylistic convention." Style is the real substance of art, content its outer decoration, the enticement to the reader's attention that allows the "experience" of art that style enables.

Sontag was unfortunately denied her wish that critical theory might move "to examine in detail the formal function of subject-matter." Academic criticism has gone in precisely the opposite direction, dismissing form altogether in order to focus on the "subject-matter" that satisfies the critic's pre-established theoretical disposition, while there's very little "critical theory" at all in general-interest publications of the sort that once published writers like Susan Sontag. Essentially, the debate over the fraught relationship between "style" and "content" is about where Sontag left it.

Unfortunately, she left it presumably resolved to her own satisfaction, but not in a way that satisfies any current attempt to advance the argument that "style is on the inside." Since the notion that subject-matter is mostly a formal function seems if anything more outlandish even than it must have in 1965, a case needs to be made for it that extends beyond Sontag's somewhat idiosyncratic account and that avoids what I consider her more serious missteps.

The most serious problem with "On Style," in my opinion, is that Sontag can't finally unburden her argument of the criticisms of aestheticism made by the moralists she otherwise castigates. It seems to me her observation that it is quite easy to keep separate "responsible and humane conduct" from "the pleasurable stimulation of consciousness" without the latter contaminating the former would entirely suffice as a rebuttal of these criticisms, but she spends a great deal of her essay—the heart of it, really—defending the notion that art should not be judged by the standard of "humane conduct, " since art and the experience of art are phenomena of "consciousness," not actions requiring moral scrutiny. In fact, immediately after making the observation she begins to back off, assuring skeptics that "Of course, we never have a purely aesthetic response to works of art—neither to a play or a novel, with its depicting of human beings choosing and acting, nor, though it is less obvious, to a painting by Jackson Pollack or a Greek vase."

Since we never have a "pure" response to anything, I can't see that this proviso is necessary. If it isn't obvious to readers that a depiction of "human beings choosing and acting" is not the same thing as human beings choosing and acting and that it would be irrational "for us to to make a moral response to something in a work of art in the same sense that we do to an act in real life," then any further attempt to heighten those readers' aesthetic awareness isn't going to accomplish much in the first place. Although Sontag argues that "we can, in good conscience cherish works of art which, considered in terms of 'content,' are morally objectionable" (her brief defense of Leni Riefenstahl's documentaries is the best-known illustration of this possibility), finally she can't let "morality" go as an issue relevant to the creation and experience of art. "Art is connected with morality," she asserts. "The moral pleasure in art, as well as the moral service that art performs, consists in the intelligen

t gratification of consciousness."

Much is elided in that formulation "intelligent gratification." Is "unintelligent" gratification immoral, or just lack of artistry? Is lack of artistry itself a moral issue, or simply a critical/evaluative judgment? Does only the greatest art perform the "moral service" Sontag associates with the "intelligent gratification of consciousness"? I don't object to the formulation itself—John Dewey would probably have found it usefully synonymous with his own notion of "art as experience"—but to insist that it must have a moral dimension seems to undo almost completely Sontag's case—which she admits she has made "uneasily"—for the autonomy of art:

But if we understand morality in the singular, as a generic decision on the part of consciousness, then it appears that our response to art is "moral" insofar as it is, precisely, the enlivening of our sensibility and consciousness. For it is sensibility that nourishes our capacity for moral choice, and prompts our readiness to act, assuming that we do choose, which is a prerequisite for calling an act moral, and are not just blindly and unreflectingly obeying. Art performs this "moral" task because the qualities which are intrinsic to the aesthetic experience (disinteredness, contemplativeness, attentiveness, the awakening of the feelings) and to the aesthetic object (grace, intelligence, expressiveness, energy, sensuousness) are also fundamental constituents of a moral response to life.

Again, there isn't much here with which I would fundamentally disgree, but Sontag comes close to suggesting that art needs this moral justification, that "contemplativeness" and "attentiveness" are not in themselves sufficiently desirable qualities. They are "moral" insofar as they are good things to exercise, but I can't see that an explicit justification of them—and thus of aesthetic experience itself—on moral grounds is otherwise relevant. Either art needs no moral justification to strengthen its appeal or it is an impetus to moral action after all. Sontag wants to believe the first, but really seems to believe the second.

To be continued

Against the grain

This essay on The New Criterion by George Scialabba (not our own Scott McLemee, thank you very muchmisattribution now corrected) has been getting some recent attention because it says harsh things along the way about cultural diversity. Although Scialabba certainly doesn’t like the culturalist left very much, his discussion of its problems are a class of a diversion on the way to the main argument of the piece, which concerns the problems of the cultural conservatives who criticize them.

the New Criterionists sometimes boast that they and not the multiculturalists are the true democrats, applying to themselves Arnold’s words in Culture and Anarchy “The men of culture are the true apostles of equality. [They] are those who have had a passion for diffusing, for making prevail, for carrying from one end of the society to the other, the best ideas of their time.” But it is a hollow boast. Arnold freely acknowledged, as Kramer and Kimball do not, the dependence of spiritual equality on at least a rough, approximate material equality.

in these and other passages Arnold demonstrated his humane moral imagination and democratic good faith. Kramer and Kimball have yet to demonstrate theirs. Finally, there is the complicated matter of disinterestedness, or intellectual conscience. That both Kramer and Kimball would sooner die than fake a fact or twist a quote, I do not doubt. But disinterestedness is something larger, finer, rarer than that. To perceive as readily and pursue as energetically the difficulties of one’s own position as those of one’s opponent’s; to take pains to discover, and present fully, the genuine problem that one’s opponent is, however futilely, addressing—this is disinterestedness as Arnold understood it.

Arnold thought he had found a splendid example of it in Burke who, at the close of his last attack on the French Revolution, nevertheless conceded some doubts about the wisdom of opposing to the bitter end the new spirit of the age. …I wish I could imagine someday praising Kramer and Kimball in such terms. But alas, I know nothing more un-New-Criterion-ish.

This, and other essays, are collected in Scialabba’s new book, which is just out (I got my copy yesterday), and which I can’t recommend highly enough. This bit, on Robert Conquest, has the quality of the best aphorisms:

It may be a delusion, as Conquest repeats endlessly, to imagine that state power can ever create a just society. But one reason some people are perennially tempted to try is that private power is generally so comfortable with unjust ones.

I’d enjoyed Scialabba’s essays very much when I read them individually, but to be properly appreciated, they should be read together. NB also that Scott, while entirely innocent of the essay quoted above, did write the introduction to the new volume.