Search for ‘Sarang Gopalakrishnan’ (9 articles found)

"It is this deep blankness is the real thing strange"

As the summer of writing papers yields to the fall of trying to find work, one is naturally much troubled by introspection — which, in my case, is of a self-pitying and/or self-accusing kind that it’s probably best not to inflict on others; hence the general hush. A few observations:

- There is much to be said for the theory that procrastination is self-sabotage. I suspect that I’m invested in telling myself that I’ve underachieved and in making this seem plausible on the merits. (The alternative, that one did one’s best but still ended up mediocre, is much more dispiriting.)

- Wasted effort is character-building. (So is putting a lot of effort into something you know you’ll never get good at; so are routine tasks that eat up a lot of your time.) I have avoided all of these to a large extent, and the consequent damage is a profound inability to get myself to work hard.

- In my case, part of the problem was that, by managing to avoid all teaching responsibilities, and not (e.g.) having a family to worry about, I managed to keep afloat relative to others — workwise — without doing very much. Had I been more driven and less indolent, I would have done more, and perhaps accomplished more; even if that effort had been wasted, I would have accustomed myself to long, concentrated spells of working. It appears to be easier to increase one’s time at work than to increase one’s efficiency: any obligation that caps work hours is a good thing.

- It is pointless to commit yourself to things that you’re not up to — however much you’d like to be up to them — on the assumption that commitments really are binding on your future self. Your future self is more slippery than you give it credit for being. Your future self is also quite good at damage control.

- An almost-snowclone: “X’s weaknesses are inseparable from his strengths.” Depressingly true of most of us, I think. I often wish I were better with details than I am, but I think that if I had (ceteris paribus) that sort of mind I would be subject to the shortcomings of the detail-oriented people I see all about me. (This is partly a numerical thing: for some reason it is rarer to find physicists who are heedless of particulars than to find those who pay too much attention to them.)

- There is no such thing as bad luck. There is unreasonably good luck, and then there is the luck we deserve.

"A black Irish beer that disappears in the course of the creative process"

Brodsky describes the daily routines of Auden, with whom he briefly stayed in Austria (I assume in Kirchstetten though the article doesn’t specify) after being kicked out of the USSR:

W. H. Auden drinks his first martini dry at 7:30 in the morning, after which he sorts his mail and reads the paper, marking the occasion with a mix of sherry and scotch. After this he has breakfast, which can consist of anything so long as it’s accompanied by the local dry pink and white, I don’t remember in which order. At this point he sets to work. Probably because he uses a ballpoint pen, he keeps on the desk next to him, instead of an inkwell, a bottle or can of Guinness, which is a black Irish beer that disappears in the course of the creative process. At around 1 o’clock he has lunch. Depending on the menu, this lunch is decorated by this or that rooster’s tail, or cocktail. After lunch, a nap, which is, I think, the only dry point of the day.

This is from a New Yorker profile of Brodsky (who apparently wasn’t gay; for some reason I had always assumed he was). There are some vaguely pleasant renderings of Brodsky’s poems; I must say that, although he has technically been fortunate in his translators (Richard Wilbur, Anthony Hecht, …), they have tended to overdo the house-training; I’ve never managed to get a handle on the idiosyncrasy (in the Fowlerian sense) of Brodsky's work.

The rhetoric of happiness

… like Ian Leslie, I dislike the “Trendy Vicar tone“ of the happiness movement, all the “stop to think about it” / “hectic pace of life” crap — and partly based on skepticism about self-reported happiness (largely dispositional, heavily socially influenced, inflected by signaling: I approve of people who respond to “how are you” with a grunt). But it also seems trivial to come up with situations that are the exact inverse of that Krugman argument: cases in which it is intuitively sensible to trade happiness for other things, like knowledge or responsibilities. For instance most works of art, and perhaps the large majority of scientific inventions — e.g., the spinning jenny — probably can’t be justified through their impact on gross human happiness, but are worthwhile in some fairly obvious sense. (One can wriggle out of this through redefining “happiness” to include every possibly valuable thing, have higher/lower forms, etc. but this is a stupid semantic game.)

Anyway, the point about “happiness” is that it is the latest buzzword for scientism in the humanities; it is what “progress” was in the era after Herbert Spencer, and (perhaps) what growth was for a while in the mid-20th. (Perhaps the era of Lagrange and Gauss, ca. 1800, was obsessed with voting systems for a similar reason.) There is an enduring tendency for the latest scientific fad — preferably something that is a little amorphous, though this seems not to be essential — to be applied to human affairs by implicitly adopting a self-serving value system according to which the one thing the new science is about is precisely the thing that’s to be maximized. Thus with psychology — evolutionary and otherwise — and happiness.

Sarang Gopalakrishnan on rationality

In this post, Alan touches on a longstanding disagreement between us on “reasonableness.” To be a little reductive, he is (like most of my friends) a firm believer in self-improvement, intuition pumps, Science, and the like; I am a nihilistic slob, with considerable sympathy for irrationalism. Part of this is, no doubt, due to differences in temperament (this is the only way I can explain the fact that I’m not a vegetarian), but differences in intellectual history also have something to do with it.

I should distinguish between contemplative and instrumental rationality: the former is about getting facts right, not believing false arguments, etc.; the latter is about getting what one wants, whatever that might be. (The former is a limiting case of the latter.) Given a list of desires and beliefs, instrumental rationality tells you what actions are (in some pretty obviously meaningful sense) “rationally binding.” In certain very specific contexts (e.g., a prisoner trying to escape), what one wants is clear, and instrumental rationality is a useful tool.

Perhaps some cases in the historical core material of economics — purely profit-maximizing regimes of endeavor — resemble this; however, whether any of it applies to everyday life is much less clear, as it is not evident that people have fixed desires in any meaningful sense. (I wholeheartedly agree with Andrew Gelman’s aphorism that “the utility function is the epicycle of social science,” which I probably consider to be more broadly true than Gelman does.) In order to adapt instrumental rationality to everyday life, one is forced to do a sort of three-step: (a) assume that a utility function exists, (b) use a combination of survey data, “revealed preference,” behavior, and intuition-pumping to figure out what the utility function says, © accuse people of being irrational when the “best” utility function doesn’t do a good job of predicting their behavior.

[…]I’ll restrict myself to a brief note on “ideology” as the term is used in physics. An “ideology” is a widely believed but vague and/or unprovable rule of thumb that can be applied to prove various specific results. It is, in general, a rule about what questions to ask and what kinds of answers to look for. The “renormalization group“ idea in physics is an ideology that plays a role that’s roughly like that played by evolution in biology: one cannot reduce it to a precise, true, non-vacuous statement, but it guides the field. Ideologies are what Weinberg refers to as the “soft” parts of theories:

There is a “hard” part of modern physical theories (“hard” meaning not difficult, but durable, like bones in paleontology or potsherds in archeology) that usually consists of the equations themselves, together with some understandings about what the symbols mean operationally and about the sorts of phenomena to which they apply. Then there is a “soft” part; it is the vision of reality that we use to explain to ourselves why the equations work. The soft part does change; we no longer believe in Maxwell’s ether, and we know that there is more to nature than Newton’s particles and forces. … But after our theories reach their mature forms, their hard parts represent permanent accomplishments.This distinction exists to some degree outside particle physics — a great deal has been learned about the lineages of various species, etc., even if the ideology that led to these discoveries turns out to be false. But it’s worthwhile to distinguish between the predictions of a theory — i.e., predictions that come out of the “hard part” — and those of an ideology, which come from the soft part. The latter cannot be disproved in any straightforward way — they are just patterns we impose on selected agglomerations of fact — and change, as often as not, because the community becomes interested in other problems where the ideology is less useful.

Auden reviews Tolkien

Auden reviewing part III of Lord of the Rings:

To present the conflict between Good and Evil as a war in which the good side is ultimately victorious is a ticklish business. Our historical experience tells us that physical power and, to a large extent, mental power are morally neutral and effectively real: wars are won by the stronger side, just or unjust. At the same time most of us believe that the essence of the Good is love and freedom so that Good cannot impose itself by force without ceasing to be good.

The battles in the Apocalypse and “Paradise Lost,” for example, are hard to stomach because of the conjunction of two incompatible notions of Deity, of a God of Love who creates free beings who can reject his love and of a God of absolute Power whom none can withstand. Mr. Tolkien is not as great a writer as Milton, but in this matter he has succeeded where Milton failed. As readers of the preceding volumes will remember, the situation n the War of the Ring is as follows: Chance, or Providence, has put the Ring in the hands of the representatives of Good, Elrond, Gandalf, Aragorn. By using it they could destroy Sauron, the incarnation of evil, but at the cost of becoming his successor. If Sauron recovers the Ring, his victory will be immediate and complete, but even without it his power is greater than any his enemies can bring against him, so that, unless Frodo succeeds in destroying the Ring, Sauron must win.

Evil, that is, has every advantage but one-it is inferior in imagination. Good can imagine the possibility of becoming evil-hence the refusal of Gandalf and Aragorn to use the Ring-but Evil, defiantly chosen, can no longer imagine anything but itself.

This idea appears repackaged in a much later poem on the Soviet invasion of Prague:

August 1968

The Ogre does what ogres can,

Deeds quite impossible for Man,

But one prize is beyond his reach,

The Ogre cannot master Speech:

About a subjugated plain,

Among its desperate and slain,

The Ogre stalks with hands on hips,

While drivel gushes from his lips.

I doubt that Auden meant the analogy between Sauron and Brezhnev seriously; this is just an example of his inveterate recycling habit — lines in the early verse, as someone said, lived a migratory existence, and similarly with ideas in the later work. And while it is smug to think of one’s opponents as morons, I think the connection here is interesting because it draws what was — to me — an unexpected parallel between LOTR and, say, The Good Soldier Svejk, in this notion that the hero of a quest is a middling, perhaps even a picaresque, character (picaro meaning rogue) flitting between the ogre’s blind spots. And there are connections with fairy tales as well, esp. the notion of the “third son” (another Auden obsession) who is not outwardly promising but is fated to win the princess.

What’s different about LOTR, I suppose, is the ethical choice to fight left-handed. It would be wrong to ignore this aspect of the books, but it does seem to me that the basic “solution” to the problem of evil that’s suggested here is that good, by choice or necessity, is effectively not omnipotent.

This connection also brings up a question I’ve never found a satisfactory answer to, which is whether the difference between picaresque and Odyssey-style epic — which is to say, most epic and quest literature; any long work of fiction in which “unity of action” is impossible and a lot of the events are there to flesh out and diversify the fictional world — is one of narrative emphasis or of structure/storyline. Could one rewrite LOTR as a picaresque in which Frodo and Sam go into the world looking for adventure and in which the ring business is a pretext for their exploring the world? How much would one have to change the plot? Similarly, how essential a plot device is Odysseus’s homesickness or Aeneas’s plodding sense of duty? Why can’t a picaresque be an epic quest for money and a spouse? (Much of Malory is akin to picaresque in its lack of direction.) Is it that the ending of one is intrinsically more provisional because the wheel of fortune keeps turning but Troy/Sauron won’t rise again?

Could one make an RPG based on Candide?

After the Cleveland School

Lord, thou hast made this world below the shadow of a dream,

An taught by time I tak’ it so—exceptin’ always steam.

From coupler-flange to spindle-guide I see thy hand O God –

Predestination in the stride o’ yon connecting rod.

(Kipling, "M'Andrew's Hymn")

Zach Sachs shared T.J. Clark’s essay about “modernism, postmodernism, and steam,” which is built around the same ambiguous symbol that Kipling is using here: steam, as an emblem both of evanescence and of machinery, represents the basic tension of modernism, which is between the anarchic individualistic tendency of modern (pre-1945) thought and the contrary, regimenting tendency of industrial life. It is surprising how close the parallels between literature and art are — when Clark says,

You could say of the purest products of modernism […] that in them an excess of order interacts with an excess of contingency.

he might as well be talking about Ulysses. (By the way, a point this essay brings home is that WW1 was a very minor part of the story, as most of the currents of modernism had been around for years.) Of course it’s much wider than that: earlier this afternoon I was leafing through Russell’s History of Western Philosophy at a Borders, looking for a passage about Locke, when I found a very close echo of Clark's thesis in Russell's remarks about how the English empiricists were driven by their arguments, against their natural temperament, to a position of extreme subjectivism that was at odds with the Zeitgeist.

So, at a minimum, the tension that Clark associates with modernism is at least as old as Hume and Blake. One is tempted to write a long essay about this but it would never actually get written — I’m too lazy to finish anything — and the point of this blog is to record my half-digested impressions without worrying about structure etc. So I’m just going to assemble a few notes.

1. Modernism is, of course, one of two successful responses to modernity, the other being Romanticism. Romanticism wasn’t a formalist movement in any deep sense; its basic tendency (seen from the modernist end of the telescope) is escapist; still, escapism might be fruitful under some conditions, and it might be that current conditions are better suited to good escapist art than to good formalist art.

2. Related to this, High Modernism was perhaps a decadent movement in Empson’s sense that it depended on a tradition that its example was destroying. The best modernist art and literature works largely through unexplained and jarring juxtapositions. The idea always seems to be to force a new emotion into existence by making you think in multiple registers, each with a certain level of vividness, at once. A lot of the juxtapositions only worked while they remained unexpected, i.e., before the first-wave modernists were assimilated. Much of the later work maintains the unexpectedness by stylizing to a degree that makes the tension unimmediate and therefore ineffective. A lot of Pound is no longer readable: the Pound of flesh is now a Pound of maggots. Looking at the pictures that accompany Clark’s text, one is tempted to say that something like this must also have happened in the visual arts beginning around Picasso.

3. An excess of contingency is implicit in an excess of form: why that pattern, one could ask, rather than any other? (The number of possibilities grows with the complexity of the pattern.) Had Keats’s odes been identical except for being acrostics, we might think them less inevitable. In Clark’s terms, Through the Looking Glass is a deeply modernist work, being schematic in the same way as Ulysses and some of the paintings Clark discusses. Victorian writing differs from Modernist writing in lacking the element of direct shock. My sense is that the shock value was primarily about forcing people to look at the work rather than through it, by frustrating their expectations. I don't think this is feasible or interesting at present because the better sort of readers have no expectations at

4. To oversimplify somewhat, the internet has resolved the central tension of modernism; the dominant tendency is currently toward solipsism, and the basic tension is between the world of windowless monads and human nature, which is reluctant to adapt to this world. (The “objective” tendency is represented by neuroscience, which “tells us” that the mind is maladaptive.) So the natural theme of fiction is psychosis, and the struggle to reimagine a reality that is perfectly intelligible on its own terms — which are Leibniz’s — in ways the mind is at home with. There have, for instance, been several novels lately — Tom McCarthy’s Remainder, Rivka Galchen’s Atmospheric Disturbances (very good!), Richard Powers’s Echo Maker (juvenile and lame), etc. — about characters who are obsessed with the fogeyish notions of authenticity and identity. (The latter two are about people with Capgras syndrome, which (for novelists) is a disorder that leaves you convinced that your family and friends are actually exact replicas of your family and friends.) I wonder if Clark has read these books and what he makes of them.

Borges and Local Color

What’s odd about Borges’s Personal Anthology is how boring it is relative to his collected works. Borges explains in a preface that he’s left out stories that were “superficial exercises in local color” (or something like that); what remain are bland and repetitive statements of certain metaphysical positions — about infinity and idealism and such — that obviously meant a great deal to Borges but are trite as philosophy. A good example of the sort of thing Borges seems to have liked in later life is “The Other Tiger“; for all I know it’s a good poem in Spanish but in translation one finds it drab and obvious. A good example of the sort of thing he did not like is “Tlon, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius.”

I wonder if this is due in part to Borges (mistakenly) comparing himself to Kafka. Jonathan Mayhew has a delightful post likening the Oxfordian theory of Shakespeare to a story by Borges or James or Kafka. I would be much more specific: such a story would have been at home among Borges’s Ficciones but has very little to do with Kafka. I am not sure, either, that a reader who knew Borges exclusively through the Personal Anthology would have perceived the accuracy of this comparison, as none of the “notes on imaginary books” are in it. It seems to me quite inaccurate to bracket Kafka with Borges at all. Kafka’s novels can be understood in textbook modernist terms, as being rather like Macbeth — successful attempts to find objective correlatives for a certain set of feelings, a certain sense the isolated mind has of its relation to the world. This will not work with Borges as the stories aren’t mood-driven. A Kafkaesque situation is a nightmare; a Borgesian situation is an artifact.

The Borges stories I like best (other than the enjoyable but silly stuff in A Universal History of Iniquity) are the notes on imaginary books and two later stories, “The South” and “Averroes’ Search,” which come off for reasons that might be fortuitous. The general problem with writing “philosophical” literature, as Eliot remarks, is that the philosophy has to be realized — fleshed out, peopled, colonized — for the enterprise to work. (One should make an exception for purely frivolous uses, like the Hitchhiker’s Guide.) A lot of Borges stories, like “The Circular Ruins,” are bad b’se insufficiently real. In later work like “The Aleph,” concreteness coexists uncomfortably with philosophical notions, but the philosophy comes off as an exotic and unjustified plot device. But in Tlon, “Pierre Menard” etc., idealism finds an odd but satisfying local habitation in names. Like Swinburne’s poems (insert more Eliot here) these stories seem to indicate that there are other worlds than the physical one that are rich and irregular enough to “inhabit” or “realize” ideas in: the world of words and literature, in particular. I wonder, though, if the truth isn’t simpler: these stories depend for effect largely on the ability of language to refract ordinary objects, say the moon, “into something rich and strange” — all literature does, I think — and lose their charm when there aren’t any objects to be looked at. I’ve expressed vaguely similar sentiments about Stevens in the past, the good bits of his poems are the half-distinct, dazzling images seen out of the corner of the eye, while he’s going on about something or other. This is probably a somewhat heretical opinion.

Why coffee stains are ring-shaped

There’s a group of clever people at the James Franck Institute (UChicago) who study some of the overlooked and bizarre regularities of everyday life — e.g. Tom Witten, Sid Nagel, Heinrich Jaeger, and Wendy Zhang. Their work has always struck me as very beautiful and “classical” in its spirit: it is the sort of thing the founders of the Royal Society, or for that matter Euler or the Bernoullis, might have studied and would have appreciated. They work on things like the flow of sand out of thin nozzles, the fact that liquids do not splash on top of Mt Everest, and the extent to which a droplet of water that pinches off a nozzle remembers the shape of the nozzle.

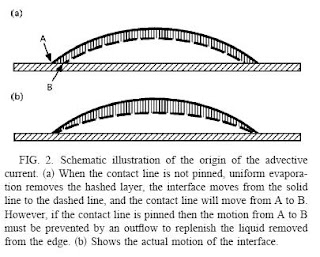

An esp. nice result that I heard about at a talk yesterday was Witten’s group’s theory of why coffee-stains have the sharp-edged, ring-like shapes they do. [The relevant references are Nature 389, 827 (1997) and Phys. Rev. E 62, 756 (2000).] The answer goes something like this: the edge of the coffee-bearing water droplet snags on surface roughnesses and gets pinned. (On sufficiently smooth surfaces, e.g. Teflon, coffee stains are not ring-shaped but uniform.) As water evaporates the bubble has to shrink; the water evaporates at roughly the same rate everywhere so ceteris paribus the bubble would want to shrink everywhere, but it can’t because that would decrease its diameter and require the edge to move, and the edge can’t move because it’s pinned. The only way to keep the edge where it is while all of the surface evaporates at the same rate is for fluid to flow from the center of the droplet to the edge, to replenish the water lost from the edge. So over time most of the water in the bubble evaporates from the edge, and most of the solute gets deposited at the edge, so the stain is ringlike.

Under certain conditions, the edge is “almost” pinned but periodically unsnags (“depins”), moves some distance, and then snags again; this leads to terrace-like stain patterns.

Summer political philosophy update

There are two different sorts of political disagreement among non-idiots — disagreements about the likely consequences of policies, and disagreements about values. In practice, people tend to conflate these, esp. where there isn’t an academic consensus, and adopt narratives that suggest that policies they disagree with would be disastrous regardless of values. This is usually, though not always, dishonest; few problems can be solved by dominance reasoning.

I’d describe myself as a left-wing individualist; I’m antagonistic in the abstract to most forms of communitarianism, unions, small-business-worship, homeschooling, extended families, nationalism, ethnic pride, segregation, etc. (And yes, from my perspective left-wing and right-wing communitarianism are similar phenomena.) On the other hand, I believe a fair bit of the negative communitarian case against modernity and modern liberalism: I’m not convinced that progress makes people happier; I agree with Naomi Klein (whom on the whole I dislike) that corporate interests corrupt politics, and that either politics must be insulated from big business or big business must somehow be shrunk (I’d prefer the former); I buy the conservative belief that diversity and urbanization spoils the sense of community and the real benefits that come with it (though I’d say, if so then fuck the sense of community). Etc.

I’m unsympathetic toward libertarianism largely because I don’t believe libertarian arguments. The value system, on the whole, I’m not that antagonistic towards. I’m in favor of wide personal freedoms, a moderately strong system of property rights — that is, I would like property rights to be strong enough that they are predictable, which is a pretty powerful constraint — and flexible employment. (On the other hand, flexible employment includes people with preexisting conditions; the current system, where some people simply can’t afford to lose their jobs, strikes me as intensely wrong. Similarly, I think that people in general ought to have the right to free speech de facto and not just de jure; one shouldn’t be liable to starve for protesting.) Lateral mobility seems at least as important as upward mobility, esp. assuming long lives and rapid technological change; I’m in favor of a reasonably strong safety net that allows people to change jobs in mid-career. And I just don’t think any of this is possible without big government and high taxes. I am quite strongly against outsourcing the safety net to families, charities, etc. because they’re bound to be discriminatory in ways I disapprove of.

I tend to distinguish between liberties that I consider valuable in themselves, e.g. the right to say almost anything you like with a reasonable shot at finding an audience, the right to a fair trial, the right to a decent education, etc., and those that are administratively useful, such as most property rights, the right to leave your money to your kids when you die, the right to read Joyce to your five-year-olds, etc. I don’t really have a problem with curbing the second kind of liberty if it serves any purpose and can be done predictably and systematically. (I’m a big fan of the rule of law: retroactive punishment, arbitrary seizure, etc. seem deeply wrong in themselves.) I approve of stuff like McCain-Feingold. Similarly, I don’t have a problem with laws mandating that private establishments can’t expel people for certain kinds of free speech, even if that seems somewhat anti-property rights.

I disagree with the linear-programming approach towards social policy, the notion that policies are best thought of as constrained optimization problems. The way I see it it’s only necessary for things to work well enough, or even not terribly, while satisfying as many constraints and desiderata as one wants to impose. Arguments that some policy change would make some system less efficient tend not to move me; the relevant question is whether they would make the system intolerably less efficient. I have a similar sort of attitude toward meritocratic objections to affirmative action (though for unrelated reasons I’m ambivalent about AA itself). If the govt forces companies to employ grossly unqualified people, or makes it impossible for e.g. whites/Asians to find reasonable employment or colleges, then that’s obviously a bad thing; if not, I don’t much care in principle if “The Best” people don’t get the best jobs. The exception to this is some areas in which there’s social utility to having a rat race because it makes people work extremely long hours, which leads to socially beneficial outcomes (e.g. research/some engineering jobs); in such cases, meritocracy provides the only sensible form of organization.

In general, I don’t find meritocracy (or its flip side, equality of opportunity) a useful concept. Opportunities are never going to be equal — even if the state ran education, some kids would get the best nannies — and in any case it’s not obvious that people with better genes deserve better outcomes. (The only argument for meritocracy I believe in has to do with encouraging hard work.) Some talent will inevitably be wasted; what matters from the point of view of progress is that meaningful opportunities should exist for people with exceptional abilities, and this condition is weaker and more enforceable than equality of opportunity.

I don’t think, however, that the current American educational and penal systems — by and large — offer meaningful opportunities even to talented poor kids in inner cities or Appalachia (never mind the third world etc.); the existence of an underclass of this kind seems to me a natural consequence of massive inequality, and also of the fact that there is, as of now, a de facto safety net for middle-class whites. If middle-class people were likelier to be locked up for trivial offences and suffered the same sorts of consequences as the urban poor habitually suffer — if enough suburban stoners ended up with AIDS — we might have a humane prison system. Similarly with busing and inner-city schools. The obstacle here is that it’s easier for the middle class to move out, insulate itself, and use its advantage in political clout to prevent busing; and the very poor end up trapped in ghettoes. I don’t see how it’s possible to address this sort of thing structurally without ensuring a more even distribution of wealth — though that is unlikely to be a sufficient condition.

One of the aspects of the communitarian critique that I find particularly interesting is the notion of the decline in the dignity of work — in pre-industrial societies, a higher proportion of jobs required skill or strength; the fashioning of worthwhile objects gave a meaning to one’s life, outside of consumption, that it is substantially harder to get out of a job at McDonald’s. (As Gregory Clark points out, it seems likely that the extent of structural unemployment — the fraction of the populace that hasn’t got the skills or the ability to do any kind of job that there is the demand for — will rise to a reasonable fraction of the populace.) This is a natural result of globalization — there is a market for only the best books, art, and (to some extent) science; both a small community and a large one naturally sustain roughly the same number of writers, and therefore a world splintered into disconnected islands would allow for a much greater fraction of the populace to take some pleasure in their skill. What the reader gains from having access to the best stuff being done is, however, enormous [though what does that mean? I don’t think it makes people objectively happier], and in the end I do believe in progress.

I started writing this down because I figured it would help me organize my thoughts; apparently it hasn’t. I’ll skip the bit about aesthetics for now.