Search for ‘MATT ’ (136 articles found)

Advertising Graphics from the Collection of Documents of Everyday Culture

April 11 to July 5, 2015. Opening: Friday, April 10, 2015, 7:00 p.m.

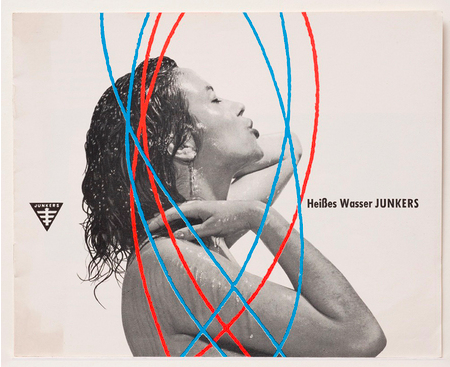

Globes, fire extinguishers, drills, cooker hoods, fur coats, roast chickens, rugs, television sets, circles, stripes, lines and colours: The Werkbundarchiv – Museum der Dinge presents a cosmos of pictures of day-to-day life with over 450 graphic advertisements from its collection of documents of everyday culture. Day in and day out, the motifs and forms of a trivial world of consumption and media appear in two-dimensional printed matter. When they land in the recycling bin, their pictures and signs disappear.

Criticism as advertisement (2009)

BRIAN DILLON Reading your essay ‘Critical Reflections’, in your recent book Art Power, I was reminded of two texts about criticism from the late 19th century. In his essay ‘The Function of Criticism at the Present Time’ (1864) Matthew Arnold writes that the critic’s job is ‘to see the object as in itself it really is’. Twenty-seven years later, in ‘The Critic as Artist’, Oscar Wilde reverses Arnold’s dictum: criticism is rather supposed to ‘see the object as in itself it really is not’. Has this distinction – between criticism as science and criticism as art – gone away, or is it still with us?

BORIS GROYS Both quotations have something to do with description, with the ability of an art critic to describe the art object in a certain way: in one case, to describe it correctly; in the other, to describe it in an interesting way or in a way that is more interesting than the correct description would be. But it seems to me – and it was on my mind when I wrote that text – that description is part of what is expected from criticism, but it’s not the most urgent thing that readers expect. What they expect is a value judgment, from somebody who has more taste than others, rather than a greater ability to describe.

And that’s precisely what seems to me to be in peril at the moment. When I came from the USSR to the West at the beginning of the 1980s, almost immediately I started to write about art for the German newspapers, and I very quickly understood that people reacted only to the fact that I had written a text, that this text was published in the newspaper, had a certain length, was illustrated or not, and was or was not run on the front page of the feuilleton section. They absolutely didn’t react to what I wrote, be it description or evaluation, and they absolutely couldn’t distinguish between positive and negative evaluation. So if they saw, for example, a long text with illustrations on the first page, and it was a negative review, everybody perceived it as a positive review. I understood immediately that the code of contemporary criticism is not plus or minus; I would say it’s a digital code: zero or one, mentioned or not mentioned. And that presupposes a completely different strategy, and a different politics.

BD What, then, are the politics of mentioning or not mentioning an artist?

BG You can escape politics as a theoretician, or as an art historian, but not as a critic. This politics excludes absolutely the possibility of being representative of the public, in whatever sense you understand that. Instead, it presupposes a certain obligation toward artists, curators and so on. You mention people that you like, and you don’t mention the people you don’t like. And you mention people because you like them, and that’s the only reason for mentioning them. If you mention them, it makes no sense to criticize them, because it’s obvious that whatever you say is an advertisement for them. If you don’t like them, you just don’t mention them; if you like them, you just approve them. So the system excludes the phenomenon of negative appreciation: something that has a very long tradition. I don’t have a feeling that negative art criticism is something people do very much now. So today’s criticism mostly does not function as a critique. Today artists want to be critical – but art criticism is almost always affirmative. It is affirmative, for example, by siding itself with art that wants to be critical.

BD It seems as though, on the one hand, criticism has lost its commitment to advancing an argument or ideology, and on the other, that critics are no longer eager to appear paradoxical: that is, to contradict themselves, even to appear hypocritical.

BG You can be hypocritical only if you say something you don’t believe in. The question is whether criticism today is a statement about one’s beliefs at all. Cultural production is based on memory: we have known that since Plato. And today, I’d say, we have lost our memories, and memory has been replaced by Google. Instead of memorizing, we are Googling. And that’s precisely what the art critic is doing. The critic creates a search engine for the reader; fundamentally, he just says, ‘Look at this!’ Whatever is said beyond this is perceived merely as an explanation or legitimization of this advice to look. People are not so interested in why they should look at it; they’re interested in the question of whether they should look at it at all. They’re also not interested in the critic’s opinion, but in whether they should have an opinion themselves about this phenomenon. I’m often asked by colleagues: ‘Should I look at this exhibition or should I skip it?’ There is a certain honesty in this: maybe there’s no reason to look at it…

BD The question ‘Should I look at it?’ suggests that, rather than enjoying or being fulfilled or improved or educated by the art object, one takes something useful from it: ideas or images that can be put to use elsewhere.

BG That’s too charitable an explanation. The question is: would you get lost in a conversation if you didn’t know the phenomenon in question? There are works and exhibitions and books that may well be awful – maybe not – but you have to have an opinion about them because, if you don’t, you are perceived as being uninformed and out of touch with whatever definition of contemporaneity you are faced with. Of course, there are a lot of things that don’t have this urgency: if I say I’m too busy to look at them, I’m forgiven for that. But with some images, some exhibitions, some books, you are not forgiven for being too busy to look into them. If I’m asked should I look at it or not, I always ponder the question seriously: would I be forgiven for not looking at this?

BD You write that the critic of the late 18th and early 19th centuries affected to makes value judgements on the basis of knowledge. He also wrote from outside the art world and deliberately distanced himself from artists. The Modernist or avant-garde critic, on the other hand, claims to speak for the art work, or for the artist. You suggest, however, that the critic is subsequently rejected by artists, whose work may very well speak for itself. How did this happen?

BG The critic has a fear and a desire, like everybody in this cultural system: he is afraid of appearing to be uninformed, not up-to-date. So he has to mention Slavoj Zizek and Alain Badiou, he has to have an opinion about Jacques Rancière, he has to know that, in contrast to yesterday, it’s not a good idea to mention Jacques Derrida but it’s a good idea to mention Gilles Deleuze and so on. So he has to be informed and to show explicitly that he is informed: that’s one source of his habit of mentioning. He mentions these people not because he’s interested in them, but because he shows that he belongs to a certain level of discourse. Then, after he establishes himself, he asks himself why and what he wants to advertise to the public.

I don’t believe in neutrality. There’s no objectivity in art. Art is not a system, not a world: it’s an area of struggle and conflict, of competition, animosity and suspicion. That’s why I’m always irritated by any systemic approach to art: as though art production is like shoe production. You have to decide what you want to advertise, what your ideological position is, what you want to make known. Of course, you’re no longer interested in criticizing anything; you’re interested in forwarding what you think is interesting for you, what should be regarded as interesting for culture in which you are living, what you’re ready to support. If you make a bad judgement, and support something that fails in a non-interesting way – because it may fail interestingly – then it was a bad choice. It’s about taking risks.

Interview with Dian Hanson

Dian Hanson has made a career of “probing the subtleties of male lust.” In 1976, she began to edit such successful fetish magazines as Juggs, Oui, Leg Show, and Outlaw Biker. Pornography, at that time, had just gone through one of its more awkward phases. Amid the psychedelia and taboo-busting of the sexual revolution, men’s magazines weren’t sure how far to go in depicting free love; an industry built on forbidden fantasy risked being outpaced by real life. Hanson is now the official “sexy editor” of Taschen Books.It does seem like there’s a remove from the magazines here and what you’re used to seeing as a representation of the movement. Do you feel like that’s common in pornography—that it exists at a remove from the culture?

Certainly it’s all inspired by the culture. But our sexuality is formed at an early age—four, five, six years old—and the guys who were looking at these magazines were guys from, say, the World War II generation. The things that were going to be triggers for them were no longer current by the late sixties. What you see are magazines made by other guys from that generation, sharing in a fantasy about the current time that doesn’t actually reflect the current time. It’s just like how we saw hippies in movies back in, say, the seventies—they didn’t look like hippies, they looked like Hollywood fantasies, idealized hippies, because they were concocted by fifty-year-old men dreaming, taking the Marilyn Monroe aesthetic and dressing it up in a fringe vest. By the time you’re actually expressing your sexuality, it’s already out of date. I can remember a man saying his sexuality came from lying on the floor watching TV westerns when he was a little boy, seeing women kidnapped and tied up and tied to the railroad tracks. By the time he grew up, it was the 1980s. Nothing like that was on television anymore. And yet this was still what aroused him. For pornography to hit his sweet spot, it had to be antiquated.

You cornered the market, especially in fetish pornography. And you’re one of the only female editors who’s famous for doing this.

There were always a lot of other women working in the business, and I knew all these women, but most of them didn’t have my enthusiasm for the subject matter, my curiosity for exploring human psychology and sexuality. A lot of them didn’t like men the way I did. I found that working at the magazines made me like men more. The more I communicated with them, the more letters I read, the more I understood the male mind and the male approach to sexuality—it made them more likeable. I saw how romantic men were. I saw that sex, for most men, was really a supreme expression of love, that they didn’t disconnect it as most people believed. Certainly most of the other women I knew in the business thought that all these men were just out for the sex and they didn’t care. Men were always falling in love with these women in the magazines, sending them gifts, projecting idealized personalities onto them. I came to see that men and women approach these things differently—women are much more pragmatic about sex and love than men are. Men are probably the more romantic of the two, and certainly more likely to be deeply wounded if a relationship ends. I would hear from men who had confessed to their wives some unusual sexual interest, who had been rejected and had never tried to date a woman again, had never dared to speak to a woman about what they were interested in. Most men approach women with a kind of combination of fear and awe.

Pattern and aboutness

We tend to read a novel first for plot and character and the narrative’s relation to reality, what post-Saussurean critics call its “aboutness,” and only secondarily, if at all, for pattern. This is a little like Ludwig Wittgenstein’s duck-rabbit argument. You know how you can draw a little circular figure with an elongation here and a dot there. If you squint your eyes one way, you can see it’s a rabbit with long ears. But if you squint another way, it becomes a duck with a protruding beak. With poems and novels, you can read for pattern or you can read for aboutness, depending on how you squint your eyes.

It happens to be the case, though, that we rarely read novels for patterns. One reason for this is that the novel’s very aboutness gets in the way. It is the easiest and most natural thing in the world to read a novel for plot and character. In fact, in most cases you have to read for plot and character in order to situate yourself, as an observer, in the world of the novel. The shift of focus, the new squint, if you will, from plot to pattern only happens on rereading. A good reader, as Nabokov wrote in his essay “How to Read, How to Write,” is a rereader.

When we read a book for the first time the very process of laboriously moving our eyes from left to right, line after line, page after page, this complicated physical work upon the book, the very process of learning in terms of space and time what the book is about, this stands between us and the artistic appreciation. When we look at a painting we do not have to move our eyes in a special way even if, as in a book, the picture contains elements of depth and development. The element of time does not really enter in a first contact with a painting. In reading a book, we must have time to acquaint ourselves with it. We have no physical organ (as we have one in regard to the eye in a painting) that takes in the whole picture and then can enjoy the details. But at a second, or third, or fourth reading we do, in a sense, behave toward the book as we do toward a painting.

When Nabokov makes a distinction between “what the book is about” and our “artistic appreciation” of the book, he is separating our reading of the subject, story and characters — the book’s aboutness — from our appreciation of the book’s so-called artistic qualities, the details we would notice if we looked at a novel the way we look at a painting.

Nabokov assumes that we all look at paintings for more than the resemblance they bear to old dead people in funny clothes, for more than romantic seascapes and sunsets. He assumes that we see, for example, Whistler’s mother as something other than an elderly lady in a plain black dress and that we know, perhaps, that the painting of Whistler’s mother was originally titled “Arrangement in Grey and Black” and that when Whistler talked about painting he would say, as he did in a letter to his friend Fantin-Latour:

…it seems to me that color ought to be, as it were, embroidered on the canvas, that is to say, the same color ought to appear in the picture continually here and there, in the same way that a thread appears in an embroidery, and so should all the others, more or less according to their importance; in this way the whole will form a harmony.

Whistler is talking about patterns, patterns of color that exist over and above and through the subject of the picture, its aboutness. And when Nabokov talks about “artistic appreciation,” he is talking about appreciating the patterns of the novel in the same way, the repetition of certain verbal events or structures in a novel like the colors in a painting. This is precisely the way we appreciate poetry, where it is, as I have said, much easier to see that sounds and words are like oil paints or, for that matter, like notes in a piece of music…

What they did was put a theory to the things painters like Whistler and, soon after, the French Impressionists, and Surrealist poets like Breton, Eluard and Ponge — all the way back to Mallarme (Nabokov sneaks Mallarme quotations into his novels) — had been doing ten, twenty, thirty or more years before. They simply recognized that aboutness and pattern were two aspects of the things we call art and language, and that you could, in fact, have pattern without aboutness.

Since it seem impossible to have aboutness without pattern, a corollary of this is that aboutness is somehow secondary, a poor cousin, on the aesthetic scale of things, to pattern. Nabokov again:

There are…two varieties of imagination in the reader’s case… First, there is the comparatively lowly kind which turns for support to the simple emotions and is of a definitely personal nature… A situation in a book is intensely felt because it reminds us of something that happened to us or to someone we know or knew. Or, again, a reader treasures a book mainly because it evokes a country, a landscape, a mode of living which he nostalgically recalls as part of his own past. Or, and this is the worst thing a reader can do, he identifies himself with a character in the book. This lowly variety is not the kind of imagination I would like readers to use.

This is what the post-Sausurrean critics, recently so popular in Europe and on American university campuses, are saying. Aboutness is old-fashioned, authoritarian, and patriarchal. Signs — read, pattern, poetry — are playful, subversive, and female. How a thinker can jump from a purely logical incongruence — the fact that, apparently, you can have pattern without aboutness but not vice versa — to these strings of value-loaded predicates is marvelous indeed and evidence that the instinct for narrative and romance has not died behind the ivy-covered walls of academe.

Another corollary of splitting the categories of pattern and aboutness is that there is a sense in which pattern itself creates meaning. Or to put it another way, the novel is about its own form. Or every book is about another book, or books. And every work of art is a message on a string of messages which begins nowhere and ends nowhere, to no one and from no one, and about nothing except the field of pseudo-meaning created by previous and future messages. It is all a game of mirrors and echoes. A little dance of images, words, and patterns. The of the Hindus, or all is vanity, all is dust, sure enough.

Keats wrote, “A man’s life is an allegory.” Nothing else. Or conversely, Korzybski says, “The map (read, the allegory, the pattern, the words) is not the territory.” Which is to say, as Jacques Lacan does, that all utterances are symptomatic and that the real is impossible.

Forward, you understand, and in the dark

For somebody who made himself so intensely, incorrigibly available, [Robert Frost] is a well-guarded figure. You could say his availability became his way of maintaining his guard. Here’s his reply to a critic who wrote in 1915 to congratulate him on his success:

Dr Mr Eaton:

It’s not your turn really. Before I have a right to answer your best letter of all there are a whole lot of perfunctory letters I ought to write to people who have been rising out of my past to express surprise that I ever should have amounted to anything. You may not believe it but I am going to have to thank one fellow for remembering the days of ’81 when we went to kindergarten together and once cut up a snake into very small pieces to see if contrary to the known laws of nature we couldn’t make it stop wriggling before sundown.

Like many of the letters, this has the makings of a Frost poem: an intimacy conjured up out of thin air, coupled with an unpredictable sense of where that intimacy might lead; talk of triumph over recalcitrant circumstances, alongside an implicit reservation about what the triumph really amounts to; and a dark toying with ‘the known laws of nature’ to see where your limits lie. A page later, Frost is talking to Eaton as if he has known him for ages (‘you know I don’t mean that’), while offering tips to the newcomer (‘I am really more shamefaced than I sound in a letter’). Eaton should feel privileged to be told that some things do not need saying, even as he is left wondering about what these other things are that are not quite being said ...

Sometimes this slippery, furtive posture makes you wonder what Frost is hiding, and sometimes it makes you wonder what you’re hiding if you don’t play along. He’s not generally the sort of person who makes a joke and then says, ‘but seriously’. His letters are instead interrupted by the phrase ‘but seriousness aside’, as if to imply that a certain type of serious thinking is holding him back from what’s really worth saying. ‘Perhaps you think I am joking,’ he warns one correspondent. ‘I am never so serious as when I am.’ He is ‘Sinceriously yours, Robert Frost’, and he wants it understood that words like ‘sincerely’ and ‘seriously’ may be overrated. This roguishness can become wearing (he sometimes flaunts it merely to get himself off the hook), but more often it indicates his willingness to explore the values as well as the dangers of being precariously placed. Humour becomes a sort of confession:

Any form of humour shows fear and inferiority. Irony is simply a kind of guardedness… At bottom the world isn’t a joke. We only joke about it to avoid an issue with someone … Humour is the most engaging cowardice. With it myself I have been able to hold some of my enemy in play far out of gunshot.

This is revealing, although the exaggerated, almost self-lacerating tone is dropped elsewhere when Frost conceives humour not only as ‘engaging cowardice’, but also as a method for engaging with cowardice by reimagining avoidance as an achievement.

Inside and outside the letters, he appears to be searching for ways to be afraid that won’t make him feel like a coward. In his introduction to Edwin Arlington Robinson’s King Jasper, he quotes a couplet from Robinson’s ‘Flammonde’ – ‘One pauses half afraid/To say for certain that he played’ – and adds:

his much-admired restraint lies wholly in his never having let grief go further than it could in play. So far shall grief go … and no further. Taste may set the limit. Humour is the surer dependence … His theme was unhappiness itself, but his skill was as happy as it was playful … One ordeal of Mark Twain was the constant fear that his occluded seriousness would be overlooked. That betrayed him into his two or three books of out-and-out seriousness.

... ‘My poems … are all set to trip the reader head foremost into the boundless,’ Frost wrote in 1927. ‘Ever since infancy I have had the habit of leaving my blocks carts chairs and such like ordinaries where people would be pretty sure to fall forward over them in the dark. Forward, you understand, and in the dark.’

Several letters in this volume – especially those in which Frost explains the acoustics of literary craft – have long been considered essential for casting light on his dark arts. ‘Free rhythms are as disorderly as nature,’ he writes to one correspondent, ‘metres are as orderly as human nature and take their rise in rhythms just as human nature rises out of nature.’ Frost wants to get into print sounds that appear to come from the body before they come from the mind. The sounds are creaturely, uncivilised things:

[A poem] begins as a lump in the throat … It is never a thought to begin with.

A certain fixed number of sentences (sentence sounds) belong to the human throat just as a certain fixed number of vocal runs belong to the throat of a given kind of bird.

All I care a cent for is to catch sentence tones that haven’t been brought to book … They are always there – living in the cave of the mouth. They are real cave things: they were before words were.

Like the strongbox, or the dark house, or the woods, the cave of the mouth is another of those Frostian dark places both cherished and feared – sometimes a shelter and sometimes a place from which one must emerge. Edward Thomas appreciatively remarked that North of Boston contained language ‘more colloquial and idiomatic than the ordinary man dares to use even in a letter’, and the letters are similarly daring. Their recipients are told that the only way to read them satisfactorily is to ‘renew in memory from time to time the image of the living voice that informs the sentences’. ‘This pen works like respiration,’ he observes, and once he’s paused for breath insists on having a conversation rather than a correspondence: ‘What do you say?’; ‘Let’s see what I was going to say’; ‘You don’t listen with much patience, I notice.’

Those who are willing to listen will notice that Frost keeps returning to one of his central principles – he calls it ‘the sound of sense’ – with devious energy. Whatever else this tricky phrase signifies, it points to the way tone enhances and complicates meaning: ‘Suppose Henry Horne says something offensive to a young lady named Rita when her brother Charles is by to protect her. Can you hear the two different tones in which she says their respective names, “Henry Horne! Charles!” I can hear it better than I can say it.’ On other occasions, Frost makes his point by rewriting the ostensibly toneless – ‘The dog is in the room. I will put him out. But he will come back’ – as the vividly toneful: ‘There’s that dog got in. Out you get, you brute! What’s the use – he’ll be right in again?’ His most famous example, in a letter to John Bartlett, is full of provocations:

The best place to get the abstract sound of sense is from voices behind a door that cuts off the words. Ask yourself how these sentences would sound without the words in which they are embodied:

You mean to tell me you can’t read?

I said no such thing.

Well read then.

You’re not my teacher.

This is a bracing yet wily prose poem of sorts. It focuses on one person’s possible misinterpretation of what the other person means, and yet just because they ‘said no such thing’ doesn’t mean they are in fact saying that they can read. ‘You’re not my teacher’ could be stalling for time or covering for embarrassment, or it could be a genuine refusal to take a lesson from this upstart pedagogue. The sound of sense can be heard clearly, but the sense that lies within or behind the sounds is not wholly clear. And that’s when we know the words, not when we’re behind the door. If that is indeed ‘the best place to get the abstract sound of sense’, what is obtained is an intimation of meaning, not its confirmation. Whichever side of the door you’re on, things are murky.

A. A. Milne: the celeries of Autumn

from Not That It Matters (1920)

Last night the waiter put the celery on with the cheese, and I knew that summer was indeed dead. Other signs of autumn there may be—the reddening leaf, the chill in the early-morning air, the misty evenings—but none of these comes home to me so truly. There may be cool mornings in July; in a year of drought the leaves may change before their time; it is only with the first celery that summer is over.

I knew all along that it would not last. Even in April I was saying that winter would soon be here. Yet somehow it had begun to seem possible lately that a miracle might happen, that summer might drift on and on through the months—a final upheaval to crown a wonderful year. The celery settled that. Last night with the celery autumn came into its own.

There is a crispness about celery that is of the essence of October. It is as fresh and clean as a rainy day after a spell of heat. It crackles pleasantly in the mouth. Moreover it is excellent, I am told, for the complexion. One is always hearing of things which are good for the complexion, but there is no doubt that celery stands high on the list. After the burns and freckles of summer one is in need of something. How good that celery should be there at one’s elbow.

A week ago—(“A little more cheese, waiter”)—a week ago I grieved for the dying summer. I wondered how I could possibly bear the waiting—the eight long months till May. In vain to comfort myself with the thought that I could get through more work in the winter undistracted by thoughts of cricket grounds and country houses. In vain, equally, to tell myself that I could stay in bed later in the mornings. Even the thought of after-breakfast pipes in front of the fire left me cold. But now, suddenly, I am reconciled to autumn. I see quite clearly that all good things must come to an end. The summer has been splendid, but it has lasted long enough. This morning I welcomed the chill in the air; this morning I viewed the falling leaves with cheerfulness; and this morning I said to myself, “Why, of course, I’ll have celery for lunch.” (“More bread, waiter.”)

“Season of mists and mellow fruitfulness,” said Keats, not actually picking out celery in so many words, but plainly including it in the general blessings of the autumn. Yet what an opportunity he missed by not concentrating on that precious root. Apples, grapes, nuts, and vegetable marrows he mentions specially—and how poor a selection! For apples and grapes are not typical of any month, so ubiquitous are they, vegetable marrows are vegetables pour rire and have no place in any serious consideration of the seasons, while as for nuts, have we not a national song which asserts distinctly, “Here we go gathering nuts in May”? Season of mists and mellow celery, then let it be. A pat of butter underneath the bough, a wedge of cheese, a loaf of bread and—Thou.

How delicate are the tender shoots unfolded layer by layer. Of what a whiteness is the last baby one of all, of what a sweetness his flavor. It is well that this should be the last rite of the meal—finis coronat opus—so that we may go straight on to the business of the pipe. Celery demands a pipe rather than a cigar, and it can be eaten better in an inn or a London tavern than in the home. Yes, and it should be eaten alone, for it is the only food which one really wants to hear oneself eat. Besides, in company one may have to consider the wants of others. Celery is not a thing to share with any man. Alone in your country inn you may call for the celery; but if you are wise you will see that no other traveler wanders into the room. Take warning from one who has learnt a lesson. One day I lunched alone at an inn, finishing with cheese and celery. Another traveler came in and lunched too. We did not speak—I was busy with my celery. From the other end of the table he reached across for the cheese. That was all right! it was the public cheese. But he also reached across for the celery—my private celery for which I owed. Foolishly—you know how one does—I had left the sweetest and crispest shoots till the last, tantalizing myself pleasantly with the thought of them. Horror! to see them snatched from me by a stranger. He realized later what he had done and apologized, but of what good is an apology in such circumstances? Yet at least the tragedy was not without its value. Now one remembers to lock the door.

Yes, I can face the winter with calm. I suppose I had forgotten what it was really like. I had been thinking of the winter as a horrid wet, dreary time fit only for professional football. Now I can see other things—crisp and sparkling days, long pleasant evenings, cheery fires. Good work shall be done this winter. Life shall be lived well. The end of the summer is not the end of the world. Here’s to October—and, waiter, some more celery.

Excerpts from an interview with Roberto Bolaño, 2001

I suppose one writes out of sensitivity, that’s all.

The truth is, I don’t believe all that much in writing. Starting with my own. Being a writer is pleasant—no, pleasant isn’t the word—it’s an activity that has its share of amusing moments, but I know of other things that are even more amusing, amusing in the same way that literature is for me. Holding up banks, for example. Or directing movies. Or being a gigolo. Or being a child again and playing on a more or less apocalyptic soccer team. Unfortunately, the child grows up, the bank robber is killed, the director runs out of money, the gigolo gets sick and then there’s no other choice but to write. For me, the word writing is the exact opposite of the word waiting. Instead of waiting, there is writing. Well, I’m probably wrong—it’s possible that writing is another form of waiting, of delaying things. I’d like to think otherwise. But, as I said, I’m probably wrong.

Plots are a strange matter. I believe, even though there may be many exceptions, that at a certain moment a story chooses you and won’t leave you in peace. Fortunately, that’s not so important—the form, the structure, always belong to you, and without form or structure there’s no book, or at least in most cases that’s what happens. Let’s say the story and the plot arise by chance, that they belong to the realm of chance, that is, chaos, disorder, or to a realm that’s in constant turmoil (some call it apocalyptic). Form, on the other hand, is a choice made through intelligence, cunning, and silence, all the weapons used by Ulysses in his battle against death. Form seeks an artifice; the story seeks a precipice. Or to use a metaphor from the Chilean countryside (a bad one, as you’ll see): It’s not that I don’t like precipices, but I prefer to see them from a bridge.

Nicanor Parra says that the best novels are written in meter. And Harold Bloom says that the best poetry of the 20th century is written in prose. I agree with both. But on the other hand I find it difficult to consider myself an active poet. My understanding is that an active poet is someone who writes poems. I sent my most recent ones to you and I’m afraid they’re terrible, although of course, out of kindness and consideration, you lied. I don’t know. There’s something about poetry. Whatever the case, the important thing is to keep reading it. That’s more important than writing it, don’t you think? The truth is, reading is always more important than writing.

Interview with Prem Krishnamurthy

Permutation 03.4: Re-Mix, Performance view with Thomas Brinkmann, 23 June 2013. All photos courtesy of Naho Kubota.

In September 2012, Prem Krishnamurthy, a founder of design firm Project Projects, opened what he called, “a Mom-and-Pop-Kunsthalle,” at 334 Broome Street, in Chinatown. Named P!, the gallery has rotated through a diverse sequence of shows. It opened with Process 01: Joy, which included prints by graphic designer Karel Martins, a social sculpture by Christine Hill, and documentary photographs by Chauncey Hare. Possibility 02: Growth, and Permutation 03 accelerated the evolution of exhibition structure, with constantly-changing incarnations of each program enlisting a wide range of collaborators including sonic sculptor Katarzyna Krakowiak, avant-garde clothing designers Slow and Steady Wins the Race, and techno-conceptual musician Thomas Brinkmann. Other recent exhibitions included French cooperative Société Réaliste and The Ceiling Should be Green, a curatorial collaboration between Krishnamurthy and Ali Wong, for which they invited a Feng Shui master to advise their choice of artists and installation.

I spoke to Krishnamurthy about the significance of iteration in his shows and the gallery’s emphasis on the juxtaposition of disciplines.

Zachary Sachs What first attracted you to the storefront that P! occupies?

Prem Krishnamurthy The first thing was the location. It was right around the corner from Project Projects. But another thing was that it was street-level. The other spaces I'd been looking at, many of them were on the second or third floor. And I think I didn't know it until I saw the place, but I found that it was very important that it be public, on the street level.I liked the weirdness of the space. It used to be an old exhaust systems contracting office, so it was divided up between two offices with interior windows between them, which seemed really strange to me, and I liked it. I saw the interior windows and immediately knew I wanted to project film works on them. And I knew that they presented an obstacle, it's not necessarily a great space for many people who want to run a gallery or exhibition space, because there's only one door. And you can only show work that fits through that door—but to me, it's a great constraint.The elements that I introduced with the architects, Leong Leong, like the moving wall, became an important part of the space, that constantly reconfigures it. It’s like a game playing piece. You cannot take it out of the space, because it’s too large.

ZS And yet it transforms the relationships between things inside.

PK That's right. It's such a simple thing, but it's these details: the fact that it's not rectilinear—it's a parallelogram. It creates these weird relationships. It was important to me that the architecture of the space not be just a passive thing, but somehow be activated.

ZS Does the architecture change with each exhibition, acting as an equal member, alongside the art? Is it more part of the curatorial voice? Or is that not a meaningful distinction?

PK Well, it is a meaningful distinction, but that's the kind of distinction that I'd call into question. Whether a decision is a curatorial decision or an artistic decision or a design decision or just a decision that is conditioned by the space: all of those things coexist. There's no definitive way to tease out whose agency a particular decision is; those things are enmeshed.

ZS And how do you see the space's context, its being in Chinatown, as participating in—or having an effect on—the shows?

PK The main thing is: if you have a gallery in Chelsea, there’s a relatively homogenous group of people that go over there. You have the High Line, but if you're in Chelsea on 22nd or 24th street between Tenth and Eleventh Avenue, you're a person going to a gallery. That's a self-selecting public. The opportunity of being in this particular spot is that it's a mixed public. Broome Street is a major access point in Manhattan—I often try to use the storefront in an active way. To make the storefront as much part of the space as anything inside of it.

ZS And so the image of the outside of the space is an aspect of every show.

PK Exactly. The signage is in Chinese and English, and there are shows that incorporate things that relate to Chinese culture in particular ways. It's true that the majority of people that end up coming here probably are from more or less the same cultural space, but then there are also always people that just stop outside. If people stop outside, even if they don't make it through the door, the space still does something. And that's important to me.

ZS And even if you end up with much the same crowd, that crowd is still taken out of the context of rows of white cubes.

PK Yes. And many people who walk in here don't know what to make of it. That’s a positive thing. I'm interested in the space feeling very, very different from show to show. And so when we did a show at the beginning of this six-month cycle on copying, where Rich Brilliant Willing worked with us to make the space into a reading room, you'd be amazed how many people said, "Oh, so you're a bookstore now? You're a reading room?" And I said, "No, it's an exhibition." And they were like, "What do you mean?"I want to create that confusion. When Slow and Steady Wins the Race opened a weeklong pop up shop here, as part of a show, same thing. "Are you a retail store? Are you selling bags or are you a gallery?" And I replied, "Both/and." It's encouraging that people still don't know what the hell we are.

ZS The emphasis on the juxtaposition of design and artwork and architecture, each being its own element of each exhibition, might serve to de-familiarize each of them from each other, right?

PK That's definitely the goal, but rather than having them be purely separate, we'd collapse the distinctions between them somehow. At the opening of Permutation 03.4: Re-mix, you could think we were a club, or something. Thomas Brinkmann was playing these records on a sound system and people were dancing, for an hour and a half or two, and there were a lot of people there purely because they were techno fans, who heard that Thomas Brinkmann was in town, and they came and they were excited. That kind of encounter is good. If we keep bringing different audiences in, and they encounter other things they might not have seen in their native context, then I think the space is doing what it wants to do.

ZS So part of what it "wants to do," in this sense would be—and correct me if I'm wrong—to break down a distinction between art and design?

PK Well, I wouldn't say it's breaking down the distinction. Because ultimately I would say those distinctions aren't there to be made but are conditional and contextual. What's design and what's art has much to do with who's doing the looking, and at what point we are in the life cycle of the object (now or in a thousand years, for example), as any other factor. So I'm not necessarily interested in the distinction between art and design (or architecture or music or fashion or fiction writing, for that matter), but rather creating a new space of viewership for it all. It’s more about putting these cultural objects into conversation, and calling out the fact that sometimes they function in similar and sometimes in dissimilar ways. Also, I'd like to create a context in which people may work in a way that is non-native to them, to have people doing things in this space that are—not, maybe, outside of their practice, but are perhaps underrepresented in their practice. And that itself is speaking to the question of disciplinary boundaries. Rather than being defined by a particular idea of what an artist does or what a designer does or what a musician does, thinking about how those things resonate with all the other ideas surrounding them. In a way, it's natural that, given that I'm a graphic designer, there's going to be a lot of design, but I don't think about it as being a space about graphic design. I think of those things as being part of the same dialogue that I have with conceptual art, or music, or architecture, and so it makes sense that those things would be brought together.

ZS It sounds like your role as the organizer is to create a place where this can happen. In one press release, I remember you say you seek, "to emphasize rupture over tranquility, and interference over mere coexistence," which in turns reminds me of an Experimental Jetset quote, something like, "design ought to perforate the thing it communicates."

PK Hmm, yeah. I hadn't heard that particular quote, but the idea of perforation is, in some ways, right—in that individual agencies are somehow made manifest, and visible, creating a rupture or break. In most art systems, there is some sort of suppression of certain kinds of agency. In many exhibitions, one talks about artists, or curators, as discrete entities that do these very discrete things. But it's clear, I think, to people who are working as artists or curators—or as designers or anything really, involved with installation—that there's a lot of overlap and ambiguity between those roles. But most of the time in the end it's cleaned up, there's a way in which things are presented as being straightforward. It's listed, who does what. Coming from a background of designing exhibitions, it seems clear that in curating a show you sometimes function as a designer, but being an artist can also mean you're organizing the work of other artists. Essentially giving a sense of display to things. And with "perforation," if you like, the idea isn't to make things disappear but to emphasize the friction.And since P! is a small space, it would be impossible to achieve that neutrality, where there's nothing else that interferes with a single work. Unless if you only showed one work. In fact, the works are always overlapping: and I think that's generally the case everywhere, but it often seems like there's a desire to push works apart, and give each of them their sacred autonomy. And there are lots of reasons why that happens in terms of the market. In here, it's both an impossibility and an intentional desire to have the works speak to each other in intimate ways.

ZS It seems like lately there's been a return to designing exhibitions in opposition to the white cube. Or as with Thomas Demand's La Carte d'Après Nature and the recreation of the 1969 exhibition When Attitudes Become Form in Venice last year, there's a lot more focus on the relationship between the space and the object. Does that feel like it's an emerging impulse?

PK When I started doing this, I wasn't thinking of it as coming from any particular place, except being a certain curatorial idea, and also a certain idea of how things were going to speak to each other. But I think you're right that one could definitely speak to related approaches in Venice this year. The idea that there are these juxtapositions between works and contexts with totally different intentions, and in being put into a space they start to create a third term. That's very much in the air now.Of course that's what graphic designers have been doing for a long time. If you're Richard Hollis designing Ways of Seeing, or any designer making a book, you're thinking about how to put together these essentially disparate forms: text and image, images of different contexts, and trying to create a thing that places them meaningfully within a space. And so I'd say that the classic tenet of graphic design is this sort of juxtaposition. Maybe it's just that it goes in and out of vogue in a curatorial sense. There are moments when one thinks more about the autonomy of the object or the autonomy of the artist, and there are moments when one thinks more about the interrelationship of objects. For example, when you're talking about re-installation of When Attitudes Become Form in Venice, that's one of the things you see. You see that, when Harald Szeemann put together the original show, the works are really on top of each other. There are these spaces where you can barely even walk through them, and maybe you think, "Oh that wouldn't even pass ADA requirements at any museum in the US." Of course in those cases it's more often than not that the neighboring objects are "like" each other. . . But I think there's still a different sense than if you're going to a show where the idea is that it is an entire space, or the work should somehow be isolated and create its own sui generis context.

ZS In another place you say you see the gallery as being "visitor-focused." How do you see that differing from, say, a traditional gallery?

PK There was a conversation that happened in Art Basel last year that outlined for me a major difference between my approach and that of a more traditional gallery model. There was a panel about mega-galleries, and a New York gallerist was saying how, as with any small business, he has to think about his clients. And his clients are artists and collectors. And he seemed to say that critical voices, like writers or the press or whatever, weren't his audience. So I asked, how do you feel about a broader public, or a different public? The response: That's not my job, to speak to a broader public.Obviously, with this project I too am speaking to a certain art and design discourse. But it's important to me that people walking by, seeing this work in the store window, don't necessarily know it's an artwork, but they look at it. Both in design, and in curating, it's a Brechtian estrangement, instead of the medium being presented as totally transparent and disappearing. It's going to affect what it's mediating one way or the other, there's no other way that it could be.

ZS Something can't not be produced.

PK Right, it can either pretend that production doesn't exist, or it can acknowledge that it does, and be straightforward about it. And I would hope to be straightforward about the fact that things are being mediated one way or the other.

ZS One line in description of the Permutation 03.x caught my eye: "multiples of a religious or political icon extend their reach and efficacy, whereas a duplicated file, painting, handbag, or cityscape violates legal and ethical strictures. Questions of capital and power lie at the core: who owns the original versus who is producing the copy." Is there a specific politics implicit in the curatorial attitude, or merely the existence of politics within this context?

PK No, there's very explicitly a politics. Part of the space is also about asking questions about commerce and culture and how intertwined those things are. In the case of this show, it's been evoked in a number of different ways. In the previous show in the cycle [Permutation 03.3], Peter Rostovsky was showing digital paintings that are distributed for free online. There was a pamphlet that we produced with him, a new text, a dialogue about painting and politics, and the question of how to create a mass-produced, democratic artwork, that's neither kitsch nor something that's elite. This came out of Peter's involvement with the Occupy movement and the contradictions it raises for artists. Such questions about distribution, and democracy are pretty intrinsic to everything we do here.

The reason that I'm interested in looking into models outside of the white cube is not just because I'm interested in breaking some norm; it's because the white cube exists to create a certain kind of value. It exists to generate a certain kind of object, to sanctify it. Display is an important and powerful thing but it's often not acknowledged. Of course it works very differently in a commercial sphere. But in any case I'm interested in making that thing apparent. It's a kind of self-reflexivity about display and how it produces value as much as it is also about the things being shown.

After all so much of normal gallery discourse is about access to knowledge. You typically have a person who sits behind a desk somewhere, and they hold the checklist and the press release. You walk in and there a lot of things on the wall, and there's nothing that tells you what they are. If you want to know what they are, you go up and get a press release. I had a strange encounter the other day. I was talking to a performing arts institution about a project, and they asked me if there was admission to the shows here, and that made me realize there's a total gulf there. We go to galleries, we're conversant in the norms. We know that if we want information, we go and ask for the checklist. If we're dressed well enough, we can ask for a price list. We know these modes and we navigate them fluidly. But the truth is many people don't. My parents walk into a gallery, they have no idea what you do there. Unless there's a wall label, they don't know who it's by, they don't know they're allowed to ask somebody. In fact the whole point of the person behind the desk seems to be to scare you into not wanting to ask.

ZS And does that gulf strike you as being another thing you're exploiting in the way you hang shows?

PK In every case we try to tweak some parameter. The second show that we did was about real estate and the scarcity of space, all of the information about the different parts of the exhibition were given on those hanging real estate signs in the front window. That had a description of each of the works and their price, if they were for sale. The idea was, a real estate office operates on a different principle: to make the information visible.

ZS Someone told me the other day that those signs in the windows of real estate offices are often not of available properties, but rather of properties that people want, which are not necessarily available. Not just the ones stamped "sold," either. Just to get people to walk in. In a sense the motivation in your display was almost the same as to the formula you copied. Speaking of which, there was a cycle of exhibitions entirely about copying.

PK Copying, yes. Really that came together from thinking about questions of originality and influence, and feeling like those were questions looming very large in my own design practice and curatorial practice. As well as from the gut impulse, that I've always had, that designers and artists tend to think about questions of influence in very different ways. There's a mode of citing things that's acceptable in one discourse but not another. But then if you cross those lines, you're allowed to steal wholesale. But it depends on whether you're doing it within a disciplinary narrative or not.

There was this book by Marcus Boon, In Praise of Copying, that I was reading when I was formulating the series. In his view, everything is a copy, in one way or another. Thus the name "Permutations.” The shows are all, in one sense, permutations of each other. They repeat each other formally, works reappearing and so on. One show has a new version of an Oliver Laric piece that was in a prior iteration of the show. And there are spatial elements that recur. So instead of thinking of something as being original, these things are really permutations of previous versions, and they're circulating fluently, and the point isn't the original idea but the specific substantiation of the thing: taking it in the own context of its making.

ZS Right, and the very word "permutation" reminds me of the Ship of Theseus paradox, where the boat is rebuilt plank by plank until no original planks are left. Is it the same ship? is it a copy?

PK In graphic design, I'm always thinking: which things are referencing other things? So, in a sense, this project is also meant as a corrective, because I tend to think of things as being very linear. In The Shape of Time George Kubler makes the point that instead of linear cycles of succession and influence, in fact influence moves in various directions, forward and backward.

ZS In a discussion of regimes in art, Jacques Rancière argued that the notion that abstract art was not something that emerged fully formed in the 19th century, but was made possible by an existing a logic of abstraction that was repeated throughout time, so in Veronese for example, there's an underlying sense of abstraction even if the paintings are ostensibly figurative.

PK Yes, exactly, and, again, in Semir Alschausky's Veronese "copy" in Permutation 3.4; that's precisely his argument. His discourse comes out of an opposition between socialist realism versus abstraction. The reason why he's interested in Veronese in particular is about how abstraction emerged from color.

Similarly, Robin Kinross cites the origin of modern typography not as the 1920s with Paul Renner or the Bauhaus, but rather in works like Joseph Moxon's 17th-century printing manual. That was the moment when printing, rather than being a "black art," guarded and guilded, started to become a skilled trade. It was the first time someone articulated the principles of typography and how to print. It became disseminate-able and open. That was, for him, the moment modern typography begins.

And obviously that's just another reframing of terms, but I think he sees what we see as being 20th-century modern typography actually coming out of this much-older movement, which has the same principles but only at a certain moment becomes self-conscious.

ZS Do you see there being any specific predecessors, in terms of curators or historical gallerists who have inspired your approach at P!?

PK The people I feel most inspired by are people like Judith Berry, who is an artist but who moves between the realms of art, architecture, exhibition design, writing, and more. Group Material was really important example for me. I wouldn't say predecessor in a direct way, but I admire them for bringing things of different contexts into a single space. In their case, much more in the mode of making an artwork: which is not what I'm interested in. I guess I also see my influences in this being less curatorial models and more wide-ranging, as design but not just design. I like the idea of a World's Fair. You put all these things together, and there they are.

ZS Okay, so, "Process," "Possibility," "Permutation"—what happens when you run out of "P" words?

PK The dictionary's pretty big. . . And, well, you know, we might be done with that thing.

True Story of My Life, by Robert Frost (1916)

Stealing pigs from the stockyards in San Francisco. Learn to whistle at five. Abandon senatorial ambitions to come to New York but settle in New Hampshire by mistake on account of the high rents in both places. Invention of cotton gin. Supersedes potato whiskey on the market. A bobbin boy in the mills of Lawrence. Nailing shanks. Preadamite honors. Rose Marie. La Gioconda. Astrolabe. Novum Organum. David Harum. Cosmogony versus Cosmography. Visit General Electric Company, Synecdoche, N.Y. Advance theory of matter (whats the matter) that becomes obsession. Try to stop thinking by immersing myself in White Wyandottes. Monograph on the “Multiplication in Biela’s Comet by Scission.” “North of Boston.” Address Great Poetry Meal. Decline. Later works. Don’t seem to die. Attempt to write “Crossing the Bar.” International copyright. Chief occupation (according to Who’s Who) pursuit of glory; most noticeable trait, patience in the pursuit of glory. Time three hours. Very intimate and baffling.

On December 2, 1948, House Un-American Activities Committee investigators were at the farmhouse of Whittaker Chambers with a subpoena. Chambers led them out of his bucolic home and to a pumpkin patch. There he took the top off of a hollowed-out pumpkin and presented them with film wrapped in wax paper.

Although there were no papers, only film, the treasonous treasure trove would be forever after known as the Pumpkin Papers. Two cylinders were of developed film and three were of undeveloped film. It turned out that some of the undeveloped film was worthless as evidence. It had been overexposed and came out blank. Others parts of the film were developed only to find that they were about trivial matters like the painting of fire extinguishers that anyone could find at the Federal Bureau of Standards of Library.

However, there were documents on that film that were of a highly sensitive, classified nature or at least it had been so when taken from the State Department. All of them were dated in the early months of 1938. Chambers claimed that most of them came from Alger Hiss. On December 6, Nixon and Stripling held a press conference at which they showed off the microfilm that had been lifted from Whittaker’s pumpkin.