Search for ‘MATT ’ (136 articles found)

The pharmacology of zombies

Excerpted from an article by E. Wade Davis in the November 1983 issue of the Journal of Ethnopharmacology. Davis, then an ethnobotanist with the Botanical Museum of Harvard University, features in Hamilton Morris’s story “I Walked with a Zombie,” in the November 2011 issue of Harper’s Magazine.

The anthropological and popular literature on Haiti is replete with references to zombies. According to these accounts, zombies are the living dead: innocent victims raised from their graves in a comatose trance by malevolent voodoo priests (bocors) and forced to toil indefinitely as slaves. Most authors have rather uncritically assumed the phenomenon to be folklore. Nevertheless, virtually all writers acknowledge that the majority of the Haitian population believes in the physical reality of zombies.

As long ago as 1938, Zora Hurston, a student of Franz Boas at Columbia University, suggested that there could be a material basis for the zombie phenomenon. Having visited what she believed to be a zombie in a hospital near Gonaive, in north-central Haiti, she concluded that “it is not a case of awakening the dead, but a matter of the semblance of death induced by some drug known to a few: some secret probably brought from Africa and handed down from generation to generation. The bocors know the effect of the drug and the antidote. It is evident that it destroys that part of the brain which governs speech and willpower. The victim can move and act but cannot formulate thought.”

Scientific interest in the zombie poison was rekindled recently by reported cases of zombies under the care of Haitian psychiatrist Lamarque Douyon. In one case it was suggested that the patient had been made a zombie by a bocor who had used a poison. Physicians close to the case recognized that the correct dosage of the proper drug could lower the metabolic rate of an individual to the point where he would appear to be dead. Cognizant of the profound medical potential of such a drug, they asked me in 1982 to investigate the composition of zombie poison in Haiti.

During the course of three expeditions, the complete preparation of five poisons used to make zombies was documented at four widely separated villages in Haiti. Although a number of lizards, tarantulas, nonvenomous snakes, and millipedes are added to the various preparations, there are five constant animal ingredients: burned and ground-up human remains, a small tree frog, a polychaete worm, a large New World toad, and one or more species of puffer fish. The most potent ingredients are the puffer fish, which contain deadly nerve toxins known as tetrodotoxin.

The effects of tetrodotoxin poisoning have been well documented. The most famous source of puffer poisoning is the Japanese fugu fish. The Japanese accept the risks of eating these fish because they enjoy the exhilarating physiological aftereffects, which include sensations of warmth, flushing of the skin, mild paresthesias of the tongue and lips, and euphoria.

Case histories from the Japanese literature about fugu poisoning read like accounts of zombification. A man who had died after eating fugu regained consciousness seven days later in a morgue. He claimed that he recalled the entire incident and said he feared he would be buried alive. Another case involved a man who walked away from a cart that was carrying him to a crematorium. Last summer, a Japanese man poisoned by fugu revived after he was nailed into a coffin.

One of the zombie patients who described his experiences to me said that he remained conscious at all times; although he was completely immobilized, he heard his sister weeping as he was pronounced dead. Both during and after his burial, his overall sensation was one of floating above the grave. He remembered that his earliest sign of discomfort before entering the hospital was difficulty in breathing. It was reported that his lips had turned blue. He did not know how long he had remained buried before the zombie makers released him. From his testimony and the medical dossier compiled at the time of his apparent death, it is evident that he exhibited twenty-one, or virtually all, of the prominent symptoms associated with tetrodotoxin poisoning.

The poisons I collected during my first two expeditions are currently being analyzed. Preliminary experiments with rats and rhesus monkeys have been most promising. Twenty minutes after a topical application of the poison to a monkey’s abdomen, the animal’s typical aggressive behavior diminished and it assumed a catatonic posture. It remained in a single position for nine hours. Recovery was complete.

These preliminary laboratory results, together with the biomedical literature and data gathered in the field, indicate that there is an ethnopharmacological basis for the zombie phenomenon. The toxins contained in the puffer fish are capable of pharmacologically inducing physical states similar to those characterized in Haiti as zombification. That the symptoms described by the zombie patient match so closely the symptoms of tetrodotoxin poisoning documented in the Japanese literature suggests that he was exposed to the poison.

From ethnopharmacological investigations, we know that the poison lowers the metabolic rate of the victim almost to the point of death. Pronounced dead by attending physicians who check only for superficial vital signs, and considered dead by family members and by the zombie maker, the victim is buried alive. Undoubtedly, in many cases the victim does die, either from the poison or from suffocating in the coffin. The widespread belief in the existence of zombies in Haiti, however, is based on those instances where the victim receives the correct dosage of the poison, wakes up in the coffin, and is dragged out of the grave by the zombie maker.

The victim, affected by the drug and traumatized by the situation, is immediately beaten by the zombie maker’s assistants. He is then bound and led before a cross to be baptized with a new zombie name. After the baptism, he is made to eat a paste containing a strong dose of a potent psychoactive drug (Datura Stramonium), known in Haiti as “zombie cucumbers,” which brings on a state of psychosis. During that intoxication, the zombie is carried off.

On Pauline Kael

Recently I’ve been reading Brian Kellow’s biography of Pauline Kael, and I’m very pleased that he’s up front about the serious flaws of “Raising KANE,” factual and otherwise — but also disappointed that Kellow is unaware that “The Kane Mutiny” — signed by Peter Bogdanovich, and the best riposte to Kael’s essay ever published by anyone — was mainly written by Welles himself. (See This is Orson Welles and Discovering Orson Welles for more about this extraordinary act of impersonation.) It appears that the main source of this doubtful assumption in Kellow’s book is Bogdanovich himself. Of course, Peter knows far better than I or Kellow do who wrote what, but one fact worthy of consideration in this matter is that he’s never reprinted “The Kane Mutiny” in any of his books (apart from the portions of his interview with Welles from that piece that I recycled in This is Orson Welles). I also happen to think that this essay is superior, as prose and as argument, to anything else ever published under Peter’s name.

I was delighted to discover that the following review is included in the collection of Welles’s papers purchased from Oja Kodar that are now housed at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. On the other hand, whether Welles read it before or after I met him is something I’ll never know. - J.R.

The conceptions are basically kitsch… popular melodrama-Freud plus scandal, a comic strip about Hearst.

Although these words are used by Pauline Kael to describe CITIZEN KANE, in a long essay introducing the film’s script, they might apply with greater rigor to her own introduction. Directly after the above quote, she makes it clear that KANE is “kitsch redeemed,” and this applies to her essay as well: backed by impressive research, loaded with entertaining nuggets of gossip and social history, and written with a great deal of dash and wit, “Raising KANE” is a work that has much to redeem it. As a bedside anecdote collection, it is easily the equal of The Minutes of the Last Meeting and Robert Lewis Taylor’s biography of W. C. Fields, and much of what she has to say about Hollywood is shrewd and quotable (e.g., “The movie industry is always frightened, and is always proudest of films that celebrate courage.”) Her basic contention, that the script of KANE is almost solely the work of Herman J. Mankiewicz, seems well-supported and convincing — although hardly earth-shaking for anyone who was reading Penelope Houston’s interview with John Houseman in Sight and Sound nine years ago (Autumn 1962). But as criticism, “Raising KANE” is mainly a conspicuous failure — a depressing performance for a supposedly major film critic — in which the object under examination repeatedly disappears before our eyes. Contrary to her own apparent aims and efforts, Kael succeeds more in burying KANE than in praising it, and perpetrates a number of questionable criticalmethods in the process. The following remarks will attempt to show how and why.

First, a word about The CITIZEN KANE Book itself, which appears to be a fair reflection of Kael’s tastes and procedures. In many ways, it epitomizes the mixed blessing that the proliferating movie book industry has generally become: one is offered too much, yet not enough, and usually too late. Thirty years after the release of CITIZEN KANE, the script is finally made available, and it is packaged to serve as a coffee table ornament — virtually out of the reach of most students until (or unless) it comes out as an expensive paperback, and illustrated with perhaps the ugliest frame enlargements ever to be seen in a film book of any kind. (1) One is grateful for much of the additional material — notes on the shooting script by Gary Carey, Mankiewicz’s credits, an index to Kael’s essay, and above all, the film’s cutting continuity — and a bit chagrined that (1) no production stills are included, (2) Carey’s notes are somewhat skimpy, and (3) apart from THE MAGIFICENT AMBERSONS, FALSTAFF, and MR. ARKADIN, no other titles directed by Welles are even mentioned (and the latter, inexplicably, is listed only under its British title, CONFIDENTIAL REPORT).

When Kael began carving her reputation in the early Sixties, she was chiefly known for the vigorous sarcasm of her ad hominem attacks against other critics. Now that she writes for a vastly wider audience in The New Yorker (where “Raising KANE” first appeared), the sarcasm is still there, but generally the only figures attacked by name are celebrities — like Orson Welles; the critics are roasted anonymously. This may be due to professional courtesy, or the likelier assumption that New Yorker readers don’t bother with film books by other writers, but it makes for an occasional fuzziness. Thus we have to figure out on our own that “the latest incense-burning book on Josef von Sternberg” is Herman G. Weinberg’s; and that when she ridicules “conventional schoolbook explanations for [KANE’s] greatness,” such as “articles…that call it a tragedy in fugal form and articles that explain that the hero of CITIZEN KANE i s time,” she is referring not to several articles but to one-specifically, an essay by Joseph McBride in Persistence of Vision. (2) The opening sentence of McBride’s piece reads, “CITIZEN KANE is a tragedy in fugal form; thus it is also the denial of tragedy,” and three paragraphs later is the suggestion that “time itself is the hero of CITIZEN KANE.” Yet taken as a whole, McBride’s brief essay, whatever it may lack in stylistic felicities, may contain more valuable insights about the film than Kael’s 70-odd double-columned pages. While it shows more interest in KANE as a film than as the setting and occasion for clashing egos and intrigues, it still manages to cover much of the same ground that The CITIZEN KANE Book traverses three years later — detailed, intelligent comparisons of the shooting script with the film (the first time this was ever done, to my knowledge), an examination of the movie’s relationship to Hearst, and a full acknowledgement (amplified by a quotation from the Houseman interview) that “Welles does play down Mankiewicz’s contribution.” And if we turn directly to Kael’s own account of KANE published in Kiss Kiss Bang Bang the same year, we find not only “conventional school book explanations” that are vacuous indeed (Kane is “a Faust who sells out to the devil in himself”), but also the assumption that KANE is “a one man show …staged by twenty-five-year-old writer-director-star Orson Welles.”

For all its theoretical limitations and embarrassing factual errors, the best criticism of CITIZEN KANE is still probably found in Andre Bazin’s small, out-of-print, and untranslated book on Welles (Orson Welles, Paris: P.-A. Chavane, 1950). It is one sign of Kael’s limitations that she once wrote in a book review about Bazin’s essays being “brain-crushingly difficult” — in English translation. A brain that easily crushed is somewhat less than well equipped to deal with intellectual subjects, as her early remarks on Eisenstein and Resnais (among others) seem to indicate. IVAN THE TERRIBLE, for her, is “so lacking in human dimensions that we may stare at it in a kind of outrage. True, every frame in it looks great…but as a movie, it’s static, grandiose, and frequently ludicrous, with elaborately angled, over-composed photography, and overwrought, eyeball-rolling performers slipping in and out of the walls….Though no doubt the extraordinarily sophisticated Eisenstein intended all this to be a non-realistic stylization, it’s still a heavy dose of decor for all except true addicts” (Kiss Kiss Bang Bang). And LAST YEAR AT MARIENBAD is “a ‘classier’version of those Forties you-can-call-it-supernatural-if-you-want-to movies like FLESH AN D FANTASY — only now it’s called ‘Jungian’” (I Lost It at the Movies). Basic to both these reactions is a refusal or inability to respond to self-proclaiming art on its own terms, an impulse to cut the work down to size — or chop it up into bite-size tidbits — before even attempting to assimilate it. At her rare best, as in her sensitive review of MCCABE AND MRS. MILLER last year, Kael can grapple with a film as an organic unity; more frequently, it becomes splintered and distributed into ungainlv heaps of pros and cons, shards of loose matter that are usually dropped unless they can yield up generalities or wisecracks, until all that remains visible is the wreckage. Many films, of course, are wreckage, and few critics are better than Kael in explaining how certain ones go over the cliff — the complex (or simple) mentality that often lies just behind banality or incoherence. But confronting the depth of KANE, she can hail it only as a “shallow masterpiece.”

Small wonder, then, that so much of the film confuses or eludes her. First she tries to “explain” as much of the film as she can by relating it to the biographies, public personalities, and (presumed) psychologies of Welles, Mankiewicz and Hearst (“Freud plus scandal”). And when some parts of the film don’t seem to match her “real-life” drama, she connects them anyway: “There’s the scene of Welles eating in the newspaper office, which was obviously caught by the camera crew, and which, to be ‘a good sport,’he had to use.” But what’s so obvious or even plausible about this fantasy when we find the eating scene already detailed in the script?

Kael is at her weakest when she confronts the film’s formal devices. The use of a partially invisible reporter as a narrative device, for instance-training our attention on what he sees and hears rather than on what he is — clearly confuses her. After criticizing William Alland in a wholly functional performance for being “a vacuum as Thompson, the reporter,” she goes on to note that “the faceless idea doesn’t really come across. You probably don’t get the intention behind it in KANE unless you start thinking about the unusual feebleness of the scenes with the ‘News on the March’people and the fact that though Thompson is a principal in the movie in terms of how much he appears, there isn’t a shred of characterization in his lines or performance; he is such a shadowy presence that you may even have a hard time remembering whether you ever saw his face…”

Quite aside from the speculation she sets up about “the scenes with the ‘News on the March’people” (isn’t there only one?), it is distressing — and unfortunately, not uncharacteristic — to see her treating one of the film’s most ingenious and successful strategies as a liability. Where, indeed, can one find the “unusual feebleness” in the brilliant projection-room sequence — a model of measured exposition, a beautiful choreography of darting sounds and images, dovetailing voices and lights — except in her misreading of it? Kael’s use of the second person here, like her resort to first person plural on other occasions, is ultimately as political and rhetorical as it is anti-analytical: one is invited to a party where only one narrow set of tastes prevails.

It’s hard to make clear to people who didn’t live through the transition [from silent to sound films] how sickly and unpleasant many of those ‘artistic’silent pictures were — how you wanted to scrape off all that mist and sentiment.

It’s hard indeed if you (Kael) fail to cite even one film as evidence — does she mean SUNRISE or THE DOCKS OF NEW YORK (lots of mist and sentiment in each), or is her knife pointed in another direction? — but not so hard if you (Kael) don’t mind bolstering the prejudices of your lay audience: they’d probably like to scrape off “all that silent ‘poetry’” too, and producers at the time with similar biases often did it for them.

Kael finds a similar difficulty in taking KANE straight:

The mystery…is largely fake, and the Gothic-thriller atmosphere and the Rosebud gimmickry (though fun) are such obvious penny-dreadful popular theatrics that they’re not so very different from the fake mysteries that Hearst’s American Weekly used to whip up — the haunted castles and the curses fulfilled.

Within such a climate of appreciation, even her highest tributes come across as backhanded compliments or exercises in condescension, as in her reversions to nostalgia. Having established why none of us should take KANE very seriously, she grows rhapsodic: “Now the movie sums up and preserves a period, and the youthful iconoclasm is preserved in all its freshness — even the freshness of its callowness.”

But if Kael can be dreamy about the past, she also records her misgivings about film as “the nocturnal voyage into the unconscious” (Bunuel’s phrase): “Most of the dream theory of film, which takes the audience for passive dreamers, doesn’t apply to the way one responded to silent comedies-which, when they were good, kept the audience in a heightened state of consciousness.” But does a dreamer invariably relate to his own dream — much less someone else’s - passively? And are “dreams” and “a heightened state of consciousness” really antithetical?

Much of the beauty of CITIZEN KANE , and Welles’style in general, is a function of kinetic seizures, lyrical transports, and intuitive responses. To see KANE merely as the “culmination” of Thirties comedy or “a collection of blackout sketches” or a series of gibes against Hearst is to miss most of what is frightening and wonderful and awesome about it. When the camera draws back from the child surrounded by snow through a dark window frame to the mother’s face in close-up, one feels a free domain being closed in, a destiny being circumscribed, well before either the plot or one’s powers of analysis can conceptualize it. As Susan Alexander concludes her all-night monologue, and the camera soars up through the skylight over her fading words (“Come around and tell me the story of your life sometime”), the extraordinary elation of that movement is too sudden and too complex to be written off as superficial bravura: a levity that comes from staying up all night and greeting the dawn, the satisfaction of sailing over a narrative juncture, the end of a confession, a gesture of friendship, the reversal of an earlier downward movement, a sense of dramatic completion, a gay exhaustion, and more, it is as dense and immediate as a burst of great poetry. At its zenith, this marvelous art-which is Welles’and Welles’alone-can sketch the graceful curve of an entire era; in the grand ball of THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS, perhaps the greatest achievement in his career, a track and dissolve through the mansion’s front door, while a fleeting wisp of garment flutters past, whirls us into a magical continuum where the past, present and future of a family and community pirouette and glide past our vision-the voices and faces and histories and personal styles flowing by so quickly that we can never hope to keep up with them.

What has Kael to say about AMBERSONS? It’s “a work of feeling and imagination and of obvious effort…but Welles isn’t in it [as an actor], and it’s too bland. It feels empty, uninhabited.” It’s nice of her, anyway, to give him an A for effort.

Throughout “Raising KANE,” a great show is made of clearing up popular misconceptions about Welles. Yet within my own experience, the most popular misconception is not that Welles wrote CITIZEN KANE (although that’s popular enough), but that he “made” or “directed” THE THIRD MAN. And the worst that can be said about Kael’s comments is that they don’t even say enough about his style as a director to distinguish it from Carol Reed’s. So intent is she on documenting Welles’vanity that the films wind up seeming secondary, trails of refuse strewn in the wake of the Great Welles Myth, and many of his finest achieve ments are denied him.

Seeing KANE again recently, she reports that “most of the newspaper-office scenes looked as clumsily staged as ever” (no reasons or explanations given). With a sweep of her hand, she consigns the rich complexity of THE LADY FROM SHANGHAI and TOUCH OF EVIL to oblivion: “His later thrillers are portentous without having anything to portend, sensational in a void, entertaining thrillers, often, but mere thrillers.” (Like James Bond?) A page later, noting “the presence in KANE of so many elements and interests that are unrelated to Welles’other work,” she takes care of those elements and interests by adding, parenthetically, that “mundane activities and social content are not his forte.” I’m still puzzling over what she could mean by “mundane activities,” in KANE or elsewhere, but if interesting social content is absent from any of Welles’later movies (including the Shakespeare adaptations), I must have been seeing different films.

A case could be made, I think, that the influence of Mankiewicz and Toland on KANE carries over somewhat into Welles’s later work, for better and for worse: MR. ARKADIN, in particular, suggests this, both in the clumsiness of its KANE-derived plot and the beauty of its deep-focus photography. But in her zealous efforts to carry on her crusade against Welles’reputation as an auteur, Kael seems to find more unity in Mankiewicz’s career as a producer than in Welles’as a director. And despite her lengthy absorption in the battle of wills between Mankiewicz, Welles, and Hearst, all she can find to say about the following quotation, from one of Mankiewicz’s letters, is that it “suggests [Mankiewicz’s] admiration, despite everything, for both Hearst and Welles”.

With the fair-mindedness that I have always recognized as my outstanding trait, I said to Orson that, despite this and that, Mr. Hearst was, in many ways, a great man. He was, and is, said Orson, a horse’s ass, no more nor less, who has been wrong, without exception, on everything he’s ever touched.

Here, in a nutshell, we have a definition of contrasting sensibilities that is almost paradigmatic: Welles (almost) at the beginning of his career, Mankiewicz (almost) at the end of his own. Considering this quote, it’s hard to agree with Kael when she writes of Mankiewicz that he “wrote a big movie that is untarnished by sentimentality,” that is “unsanctimonious” and “without scenes of piety, masochism, or remorse, without ‘truths.’” KANE, on the contrary, has all of these things, and never more so than when it entertains and encourages the idea that Kane is “a great man,” and worships raw power in the process of condemning it. It is a singular irony that the aspect of KANE that Kael writes about best — Welles’s charm as an actor — is precisely the factor that makes the script’s corruptions, obeisance to wealth and power (and accompanying self-hatred), palatable. But when similar sentimental apologies for megalomania occur in ARKADIN and TOUCH OF EVIL, they carry no sense of conviction whatever. One suspects, finally, that KANE’s uniqueness in Welles’work largely rests upon the fact that it views corruption from a corrupted viewpoint (Mankiewicz’s contribution), while the others view corruption from a vantage point of innocence. By abandoning the “charismatic demagogue” and “likeable bastard” — the sort of archetypal figure that commercial Hollywood thrives on, in figures as diverse as Hud and Patton — Welles gave up most of his audience; but it could be argued, I think, that he gained a certain integrity in the process.

The overwhelming emotion conveyed by KANE in its final moments is an almost cosmic sense of waste: an empire and a life that has turned into junk, and is going up in smoke. If we compare this smoke to the smoke that rises at the end of THE TRIAL, we may get some measure of the experience, intelligence, and feeling that Mankiewicz brought to CITIZEN KANE. Yet thankful as one may be to Kael for finally giving him his due, one wishes that some of the despair and terror of KANE’s ending had found its way into her tribute. Perhaps if, as Kael claims, KANE “isn’t a work of special depth or a work of subtle beauty,” the ending may be just another joke in what she calls “almost a Gothic comedy” — the final blackout gag. But for some reason, I didn’t feel like laughing.

Gordon Matta-Clark Postcard

SOLD

Hand cut 4 × 6 postcard. Unsigned. From the 1977 Image Bank Postcard Show.

'160 km' at Kid Yellin

Installation view of “160 km” at Kid Yellin, Brooklyn, New York, through November 6, 2011.

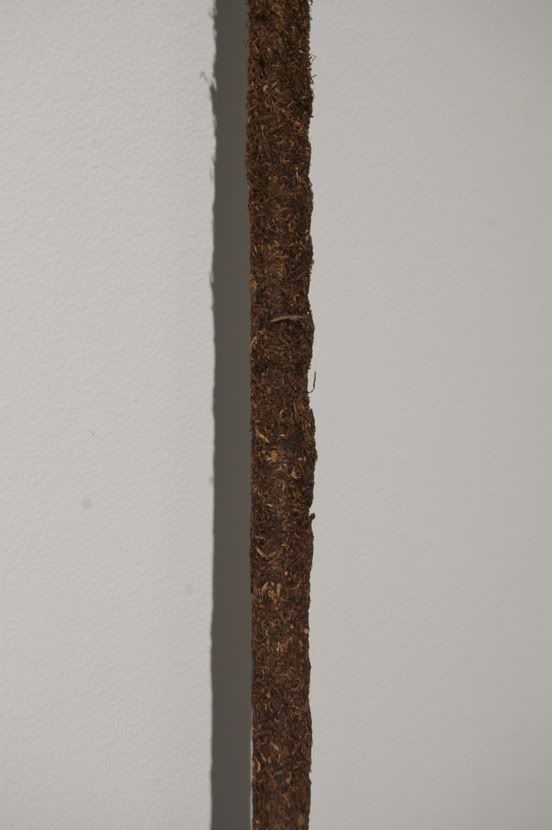

“160 km,” the current show at Kid Yellin in Red Hook, derives its title from the fact that somewhere around 90 percent of Canadian residents are believed to live within 160 km—or about 100 miles—of the border with U.S. This is, at least, what Kayla Guthrie says in a moving essay about drives along the coast of British Columbia. We are dealing, in other words, with slight separations—partial awarenesses across short distances. Also, all ten of the artists are from Canada.A few of them are young and promising, while others were, for me, totally unknown. In the former camp is Elaine Cameron-Weir, who is here (albeit too briefly) with two sculptures, one of which is 100 (steel) (2011), a thin steel rod propped against a wall, covered with brown tobacco that looks like moss. A quiet, crucial grace note in her one-person show at Ramiken Crucible back in May, it looks tough and strong on its own.

“160 km,” the current show at Kid Yellin in Red Hook, derives its title from the fact that somewhere around 90 percent of Canadian residents are believed to live within 160 km—or about 100 miles—of the border with U.S. This is, at least, what Kayla Guthrie says in a moving essay about drives along the coast of British Columbia. We are dealing, in other words, with slight separations—partial awarenesses across short distances. Also, all ten of the artists are from Canada.A few of them are young and promising, while others were, for me, totally unknown. In the former camp is Elaine Cameron-Weir, who is here (albeit too briefly) with two sculptures, one of which is 100 (steel) (2011), a thin steel rod propped against a wall, covered with brown tobacco that looks like moss. A quiet, crucial grace note in her one-person show at Ramiken Crucible back in May, it looks tough and strong on its own.

Elaine Cameron-Weir, 100 (steel), 2011, rolling tobacco, 96 × 5 × 5 in.

Kid Yellin is gigantic, and the show is sparsely populated, so there is room for everything and everyone to breath—even on opening night, October 8. Only a few sculptures—including two wild Rochelle Goldbergs (one nine feet tall), a Cameron-Weir and a Ben Schumacher floor work—are in the gallery's main room. The Schumacher, titled 217 251 (2011), consists of a long white faucet (Glacier Bay brand, the checklist says) wrapped with translucent micro-mesh that the artist printed with a light-blue metallic streak.

Ben Schumacher, 217 251 Chrome, 2011, inkjet print on micro-mesh, plaster, Glacier Bay bath faucet, steel, staples, inkjet print on paper, 24 × 72 × 4 in.

An untitled Lukas Geronimas, in a side gallery, looks uncannily similar to that Schumacher, though Geronimas’s streak is a lustrous gold—gold leaf, as it happens—that he has made to glide across a blue canvas. His work is varied. Two pieces consists of large spools of paper—pale yellow and green—each hanging from a wall-mounted rack like maquettes for Craig Kauffman’s hanging pieces. They are a little beat up, a little worn, and a fluorescent light hangs on the bottom of one, its cord stretching loosely to an outlet on the floor. Another is a simple mahogany grid made of four squares, which is almost imperceptible near the gallery’s entrance.

Lukas Geronimas, Untitled, 2011, dyed canvas, gold leaf, dust, metal, waxed string, wood, 12 × 16 in., and Rochelle Goldberg, Flatlander, in space, vertical, 2011, wood, background paper, paint, acrylic polymer, 108 × 21 × 12 in.

Aaron Aujila’s work was a nice surprise: just two tall white pieces hung on a wall that look like slabs of a prefabricated room interior. Austere and honest and a little bit funny; Anne Truitt’s 1961 picket fence, First, made contemporary and cheap. Also on view: works by Dylan Eastgaard, Shawn Kuruneru, Matt Creed, Robin Cameron, and Ryan Foerster.

Aaron Aujla, Divine Pleasure, 2011, wood cast polyurethane, joint compound, and acrylic house paint, 80 × 40 in., and Aaron Aujla, Vermont Cream, 2011, wood, cast polyurethane, joint compound, and acrylic house paint, 80 × 40 in.

Rochelle Goldberg, Exit Through the Inside, 2011, cardboard, Hydrocal, paper pulp, paint, 72 × 12 × 12, and Robin Cameron, Dancing while drawing, 2011, oil stick and oil pastel on paper, 60 × 88 in.

Lukas Geronimas, Subtitled, 2011, mahogany, textile, brass, tacks, string, adhesives, metal, 50 × 32 in., and Lukas Geronimas, Subtitled, 2011, mahogany, paper, plastic, brass, string, tacks, fluorescent light with transformer, wiring, 62 × 57 in.

Later, after a burger and beer at Brooklyn Ice House, I ran into an art dealer who was heading to a nearby bar. He was also curious about Aujila’s work, and said that it reminded him of Gordon Matta-Clark’s Bingo (1974), just a bit, the long section of a house that was on view at the second floor of the Museum of Modern Art until last month. I was excited, and pleasantly annoyed, because I had been thinking the same thing a few minutes earlier, and had been really pleased with the idea.

The Terrence Malick of rockers

![]()

Lindsey Buckingham

You’ve certainly shown on your new album that it’s possible to write from every juncture in life.

I’ve been more prolific in the last six years than ever before. I’ve done three solo albums. But before, I was the Terrence Malick of rockers in terms of these large gaps in between solo projects. There were points in time where a project that began as a solo album ended up getting folded over and made into a Fleetwood Mac album — that was the small machine getting swallowed up by the big machine. But yeah, I think that having a very collected environment, a sort of cool base from which to move out [helps], because you have to get a little neurotic and a little psycho at times in order to be creative, but it’s a little more difficult when the rest of your life is that way, too. It’s nice to be able to come back and have a safe harbor to draw from, just in terms of what’s real and what isn’t.

You’ve said in interviews that you’re finding the process of writing songs increasingly mysterious. Can you elaborate on that?

I might have been referring to the lyrics more than anything. I feel like I’m getting better as a lyricist because I’m getting a little less literal. The whole process of putting lyrics together becomes more poetic and obscure or subjective, a bit of a Rorschach. And there have been times, more than once on this album, when I was responding to things, combinations of words, without any intention. And I wouldn’t necessarily know what it was I was saying until I put it all together, and then I took a look at it and go, “Oh, I see what that means.” To me, that’s kind of exciting and that represents a level of growth from the “I love you baby, you left me” kind of mentality.

You’ve talked about the Fleetwood Mac reunion tour [in 2009] fueling “a residue of momentum,” a sense that when you do these big tours with Fleetwood Mac it also feeds the other work that you’re doing, and vice versa. Is it symbiotic?

Sure. The larger machine clearly feeds the financial side of things. There never would have been an opportunity to make solo records without that preceding it. For me, it’s been a different kind of scene than, say, what Stevie chose to do or was able to do. What she did was sort of an extension of what she was doing in Fleetwood Mac, whereas I was kind of turning around and biting the hand that fed me. And the irony of some of that is that I don’t think the label ever fully got behind my solo work, because I think they looked at it and kind of went, “What the hell is this? Let’s get back to what really matters.” There was a schizoid quality, going from one thing and then moving way over to the left, and then coming back to the right. The pendulum would swing back and forth.

Stevie has a new album out as well, to which you contributed. After all you’ve been through, not just with Stevie, but with the rest of the members of the band, how do you maintain such seemingly healthy relationships with each other? Are you guys just in therapy all the time?

If you try to imagine the process of making the Rumours album, Stevie and I had just broken up and I was trying to produce that record. I tried to make the choice to do the right thing for her every day. Four out of five of us were experiencing turmoil and had to kind of seal it off and had to deny that it was there in order to just get on with what needed to be done, because suddenly there was this calling that we had to fulfill. But I had known Stevie for years before we were a couple, since we were in high school. So it’s kind of an epic story if you look at it from the overview of these two people who obviously have a lot of regard for each other and yet had to do what they had to do and were not really able to address the feeling part of it much of the time. It left this lurching that over time has been slowly adjusted. Over the years and certainly in fairly recent times, Stevie and I have had our difficulties, but the fact that we’re still working on it speaks to the depth of the connection. I’m not really sure how you define that connection at this point, but it’s clearly there and clearly some of what I’ve done has been motivated by things that happened with her, and vice versa.

She recently referred to you two as “miserable muses.”

Well, like I said, there was a calling. That first album before Rumours had done well right off the bat, and it was clear that this band had incredible chemistry on a musical level, not just on a personal level. We had to fulfill that destiny, if you want to get a little flowery about it. It was very difficult for me — the irony of working every day to help someone move away from you, basically. It was very bittersweet, but there’s a big lesson there.

What do you mean, “helping someone move away from you”?

Helping her to move away from me as a person and as an artist, because we started off as a duo and then we joined the band. At some point, her image and her style and her voice … the things that were most appreciated by the machinery — that was waiting in the wings for her in a way that it wasn’t for me, because I was way off to the left and people were going, “What the hell is that?” So by being a part of the mechanism that was for her visibility, I was helping her to move farther away from me.

Bands on all sides of the sonic spectrum often name-check Fleetwood Mac. Do you know that? I think when you ask cool indie rockers what their secret favorite album is, nine times out of ten they’ll say, “Tusk, best songwriting of all time.”

I do feel like my street cred is as good as it’s ever been. Does that translate to marketability? Probably not. But, you know, that’s a whole other story, and also: Who cares?

Barney Rosset and the history of Grove Press

Grove cover image by Roy Kuhlman

After the war, Rosset returned to Chicago, joined the Communist Party, and hooked up with a Parker schoolmate, the painter Joan Mitchell, a key figure in Grove’s early history. Rosset followed Mitchell first to New York, where she introduced him to her circle of friends, the Abstract Expressionist painters who were in the process of stealing the idea of modern art from Paris, and then to France, where the two would marry. According to Rosset, witnessing Mitchell’s development as a painter transformed his understanding of the visual arts: “If I have any taste today, or any emotions about art…it’s all thanks to Joan.” When they returned to New York in 1951, they began to drift apart, but remained friendly; it was Mitchell who heard about Grove and encouraged Rosset to purchase it. In that same year, Roy Kuhlman, a painter on whom Mitchell had been an influence, came to the Grove offices to show Rosset some ideas for book cover design. Rosset was initially uninterested in his portfolio, but as Kuhlman was leaving he accidentally dropped a 12” by 12” piece of abstract art he intended to pitch as a record cover to Ahmet Ertegun. Rosset immediately saw what he wanted.

Steven Brower and John Gall have called the collaboration between Rosset and Kuhlman, which lasted for twenty years, “a marriage of imagery and the written word that had not been seen before, or, perhaps, since.” Kuhlman was one of the first book designers to incorporate abstract expressionism into cover art, and his signature style, making ample use of “negative space,” provided a distinct look for Grove throughout the fifties and sixties.

At one point in our second interview, Rosset made a sweeping gesture with his hand and said, “All of Grove Press’s life was within about four blocks of here.” At first, he ran the company out of his apartment at 59 West 9th street. In 1953, he moved to a small suite of offices above an underwear store at 795 Broadway, across the street from Grace Church. By that time, the Abstract Expressionists had made the Museum of Modern Art into a major player in the international art scene, the Living Theater was radicalizing American drama, and the Beats were developing their “new vision” for an indigenous avant-garde. The American Century had arrived, and New York City was its capital. If Rosset himself is a product of pre-war Chicago, Grove Press could only have happened in post-war New York.

It could also only have happened in the fifties. Rosset purchased Grove at a transitional moment in the paperback revolution that was democratizing reading in the United States. Piggybacking on the distribution networks of mass-market magazines, most paperback books in the forties were reprints either of bestselling hardcovers or of out-of-copyright classics. Initially, Rosset pursued this route, developing his title list by reprinting classic texts such as Matthew Lewis’s The Monk and Henry James’s The Golden Bowl. But soon, inspired by vanguard presses like James Laughlin’s New Directions and Jason Epstein’s groundbreaking Doubleday imprint Anchor Books, Grove began publishing original avant-garde texts as inexpensive “quality” paperbacks. Following the example of Epstein, who promoted his imprint with the Anchor Review, Rosset launched the Evergreen Review in 1957, and in 1958 the “Evergreen Originals” imprint. Grove operated on a shoestring, paid small advances, and was almost always on the verge of going under. (During our second interview, Rosset claimed, “We only made money for a couple of years,” and then, after a pause, concluded, “We never made money really.” His current modest circumstances — one associate told me Astrid had sold her house to keep them afloat — confirm Rosset’s claims.)

'Cleanup Time,' February 2000

XTC

Apple Venus Volume 1

(TVT)

Since their outtakes weren’t even rags or bones and their idea of a class pop arranger was the same as Elton John‘s, I figured that if they were feuding with their record company their record company was right. But after years of orchestral fops a la Eric Matthews and Duncan Sheik, I’m ready for McCartney fans who can festoon their famous tunes with something resembling wit and grace. Studio rats being studio rats, the lyrics aren’t as deep as Andy and Colin think they are, but at least irrelevant doesn’t equal obscure, humorless, or lachrymose. The next rock and roller dull-witted enough to embark on one of those de facto Sinatra tributes should give Partridge a call. B PLUS

Pick Hits

Jay-Z Vol. 3 . . . Life and Times of S. Carter

(Roc-A-Fella)

Sean Carter isn’t the first crime-linked hitmaker with a penchant for kicking broads out of bed at 6:15 in the morning. Frank Sinatra beat him to it. Right, Sinatra never boasted about his own callousness—not publicly, in song—and that’s a big difference. Jay-Z has too many units tied up in playing the now-a-rapper-now-a-thug “reality” game with his customers, thugs and fantasists both, and only when he lets the token Amil talk back for a verse does he make room for female reality. But the rugged, expansive vigor of this music suggests both come-fly-with-me cosmopolitanism and the hunger for excitement that’s turned gangster hangouts into musical hotbeds from Buenos Aires to Kansas City. You don’t expect a song called “Big Pimpin’ “ to sound as if the tracks were recorded in Cairo. This one does. A

Goodie Mob

World Party

(LaFace)

Not to truck with the boogie bromide that spiritual uplift requires certified fun, but this album is anything but the pop retreat the conscious slot it as. Quiet as it’s kept, message was always icing for these Dirty South pathfinders anyway, and this is the first time their music has ever achieved the infectious agape that’s always been claimed for it. The mood recalls early go-go—a funk so all-embracing that anyone who listens should be caught up in its vital vibe. But after 20 years of hip-hop, the rhythmic reality is far trickier than Chuck Brown or Trouble Funk ever dreamed—as is Cee-Lo's high-pitched overdrive, which may yet be remembered as one of the great vocal signatures of millennial r&b. A MINUS

Dud of the Month Christina Aguilera

(RCA)

“Genie in a Bottle” was such a dazzlingly clever piece of teen self-exploration cum sexploitation that it seemed the better part of valor to hope it was a fluke. But this was avoidance—like LeAnn and unlike Britney, Christina already has “adult” grit and phrasing down pat, and so threatens to join Gloria, Mariah, Celine, and LeAnn herself in the endless parade of Diane Warren-fueled divas-by-fiat hitting high notes and signifying less than nothing. “What a Girl Wants” is clever, too, but in a far less ingratiating way—like its two-hour promotional video writ small, it raises the question of how this ruthlessly atypical young careerist can presume to advise girls not cursed with her ambition, and the fear that some of them will make her a role model regardless. Give me Left Eye any day. C PLUS

Yve-Alain Bois on Martin Barre

Martin Barre, 60-T-44 (details), 1960, oil on canvas, 76 1/2 × 38 1/8”.

… In the second canvas, 60-T-44, dating from 1960, all this elaborate painterly cuisine so vaunted by the critical establishment that championed the JEP has disappeared. Any spatial ambiguity is gone. The white ground is plain, untextured, the paint almost mechanically applied. On this whitewashed surface, Barre has drawn colored lines using the tube of paint as his stylus: Two oblique lines (made of juxtaposed blue, white, and reddish-brown tracks) descend toward the center left of the canvas, from which hangs a thick rainbow of paratactic lines in clashing vibrant chromas—as if the canvas from one of Morris Louis’s Unfurleds had been gathered like striped drapery, regaining in the process enough matter to weigh down a clothesline. Here there’s no subtle mediation via the brush: The gesture is direct, prosaic. No play of underlayers, either, and very little color mixing. The only variation is in the speed of inscription: Sometimes the squeezed tube moved very fast over the white ground, and in these passages its track is thin; sometimes it went slowly, and the impasto built up. Line becomes a mere index of process. No transcendence, no illusion, what you see is what you see: With this work, and others of the same series—which he nicknamed his “Tubes”—Barre left post-Cubism and entered the ’60s.

At the time there were few artists among his Parisian group (the JEP) to make such a leap—in fact, Barre instantly lost his support system, the critics who had defended him now accusing him of treason. One could ascribe many causes to this radical turn in his art, but the most important catalyst is probably the great interest Barre took in Yves Klein, though Klein was deemed a thorough charlatan by Barre’s circle—and note that it is Restany, Klein’s champion, who came to Barre’s defense. The position may seem utterly banal now, but rare then was the artist who could at the same time maintain that painting was still a viable medium and admire Klein’s work, which had seemed in those days yet another celebration of the death of painting. One had to be able to look beyond Klein’s histrionics and consider Yves-le-Monochrome’s anticompositional stance as being more than a mere conceptual gesture. For his early admirers both in France (Restany, the Nouveaux Realistes group) and in the US (Donald Judd, among others), Klein represented a fundamental rupture with the (necessarily illusionistic) tradition of painting. “Sure, sure,” we can hear Barre saying, “but yet he still paints.” How to highlight the fragility of painting as medium while keeping it alive would remain Barre’s challenge in all the years to come.

A Global Portrait of Red Tape

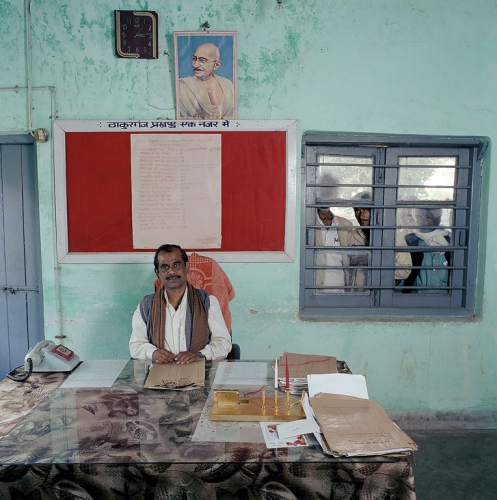

India, bureaucracy, Bihar, 2003. India-21/2003

Dr. Munni Das (b. 1960) is Block Development Officer in Thakurganj block, an administrative entity within Kishanganj district, State of Bihar. Monthly salary: about 10,000 rupees ($220)

To preserve a maximum degree of authenticity, he kept the visits unannounced, preventing the subjects from tidying up for the interview.

India, Bihar, Bureaucracy, 2003. India-28/2003

Om Prakash (1963) is Block Development Officer (BDO) in Makhdumpur Block (200.000 inhabitants), district Jahanabad, Bihar. Prakash has 45 subordinates and is responsable for public order and the development of his block. As the highest civil servant in Makhdumpur, he has a towel on his chair. The plate behind him contains the names of his predecessors. Monthly salary: 12,000 rupees ($263)

Bolivia, bureaucracy, Potosi, 2005. Bolivia-13/2005

Rodolfo Villca Flores (b. 1958) is chief supervisor of market and sanitary services of the municipality of Betanzos, Cornelio Saavedra province. Previously he worked as a bricklayer, electrician, plumber and handyman. Monthly salary: 1,150 bolivianos ($143)

Bolivia, bureaucracy (police), Potosi, 2005. Bolivia-08/2005

Constantino Aya Viri Castro (b. 1950), previously a construction worker, is a police officer third class for the municipality of Tinguipaya, Tomas Frias province. The police station does not have a phone, car or typewriter. Monthly salary: 800 bolivianos ($100)

Bolivia, bureaucracy (police), 2005

Marlene Abigahit Choque (1982), detective at the the Homicide Department of the Potosi police. The department has only broken typewriters, no computer, no copy machine, not even telephone. It shares a car with the Vice Squad: ‘If there is no petrol in the car, we have to buy it from our own money. If the car is gone, we take the bus. We have to pay the tickets ourselves.’ The head on the cupboard to the right is used to make witnesses of murder cases show where the bullets went in or out. Monthly salary: 920 bolivianos ($114)

China, bureaucracy, Shandong, 2007. China-09/2007

Wang Ning (b. 1983) works in the Economic Affairs office in Gu Lou community, Yanzhou city, Shandong province. She provides economic assistance to enterprises in her region and is the liaison officer between the government and local enterprises: she helps them get a permit for land use, personnel insurances, environmental permits and taxation registration. There was (at the time) no heating in the room. The maps show regional industrial zones. Wang Ning is not married. She lives at home with her parents. She works from 8.30 to 12 am and from 14 to 16 am. She has no official paid holidays, except the national bank holidays and the weekends. Monthly salary: 2,100 renminbi ($260)

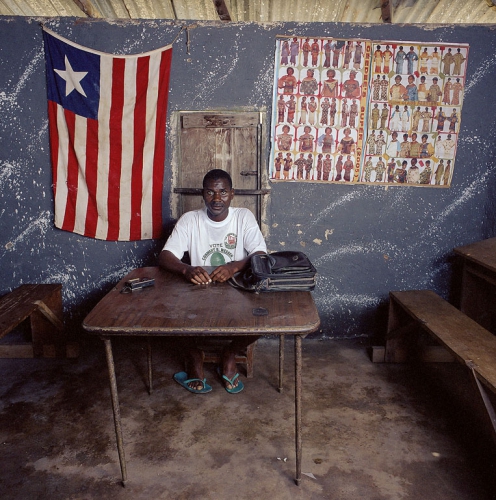

Even the visual narrative of the book exudes the monotony of its subject matter: Shot from the same height, with the same and from the same distance, and framed in an appropriately square format, the 50 subjects may vary greatly in age, appearance and location, but appear somehow homogenous in their shared slavery to paperwork.

France, bureaucracy, Auvergne, 2006. France-05/2006

Maurice Winterstein (b. 1949) works in Clermont-Ferrand for the Commission for the Advancement of Equal Opportunity and Citizenship at the combined administrative offices of the Auvergne region and the Puy-de-Dome department. He also is in charge of the portfolio of religious affairs, Islam in particular. Monthly salary: 1,550 Euro ($2,038). The young lady next to him is Linda Khettabi (b. 1989), an intern pursuing training as a secretary.

France, bureaucracy, Auvergne, 2006. France-16/2006

Roger Vacher (b. 1957) is a narcotics agent with the national police force in Clermont-Ferrand, Puy-de-Dome department, Auvergne region. Monthly salary: 2,200 Euro ($2,893).

Liberia, bureaucracy, 2006. Liberia-04/2006

Major Adolph Dalaney (b. 1940) works in the Reconstruction Room of the Traffic Police at the Liberia National Police Headquarters in the capital Monrovia. Monthly salary: barely 1,000 Liberian dollars ($18). Traffic accident victims at times are willing to pay a little extra if Dalaney’s department quickly draws up a favorable report to present to a judge.

Liberia, bureaucracy, 2006. Liberia-19/2006

Warford Weadatu Sr. (b. 1963), a former farmer and mail carrier, now is county commissioner (administrator) for Nyenawliken district, River Gee County. He has no budget and is not expecti

ng any money soon from the poverty-stricken authorities in Monrovia. Monthly salary: 1,110 Liberian dollars ($20), but he hadn’t received any salary for the previous year.

Russia, bureaucracy, Siberia, province Tomsk, 2004. Russia-19/2004

Marina Nikolayevna Berezina (b. 1962), a former singer and choir director, is now the secretary to the head of the financial department of Tomsk province’s Facility Services. She does not want to reveal her monthly salary.

Russia, bureaucracy, Siberia, province Tomsk, 2004. Russia-23/2004

Sergej Michailovich Osipchuk (b. 1974) is the lone police officer in the village of Oktyabrsky (some 2000 inhabitants), Tomsk province. He does not have a police car or one of his own, not even a bicycle. He does not want to reveal his salary, but informed sources put the monthly salary of an officer of his rank and age at approximately 4,000 rubles ($143).

USA, bureaucracy, Texas, 2007. USA-11/2007

Shane Fenton (b. 1961) is sheriff of Crockett County (about 3000 inhabitants), Texas, and based in Ozona, the county seat. Monthly salary: $3,166

Shirley Braha's Weird Vibes

Before we get into this weekend’s many show options, I’d like to write about the current state of the Music Video Program, of which there have been a couple of recent developments. I don’t know how many of you watched the return of MTV’s classic alt-rock video show 120 Minutes to the airwaves (or your digital cable provider) the other week. (I DVR’d it.) In college, used to fight with folks in the dorm lounge who were more interested in SportsCenter for rights to watch the same Mighty Lemon Drops, Nine Inch Nails and Morrissey videos they showed the week before and the week before. But in those pre-internet days, it was one of the few places you could see videos by bands/artists like that and you took what you could get.

I guess it was nice seeing Matt Pinfield‘s familiar face again, at that epicenter of NYC alt rock Arlene Grocery, but… the show felt safe, and stuck in ’90s. (I know that’s when Pinfield hosted it, but my favorite host was smartass Kevin Seal. Worst host: Lewis Largent). Pinfield talked a lot about "music discovery" which is fine until you play a Mumford & Sons video and then interview Kings of Leon. The only edge to the show was when Das Racist were on and hit line drives back at Pinfield's softballed questions.

A much better option, in my opinion, is Weird Vibes — the new web-only indie rock video show that launches today on MTV’s Hive site. The show is from Shirley Braha who was also behind the much-missed NY Noise which aired on NYCTV for much of the ’00s. Apart from the Saved by the Bell opening credits, this is a show that could only exist in 2011.

There are videos of course — Grimes, Wu Lyf, Vivian Girls, and Shabazz Palaces and more in the first episode — but you can watch those anywhere. Weird Vibes’ reason to watch is the host segments. Not that there is a host. (There is no host.) If it’s anything like NY Noise, expect the format and theme to change week to week… but the debut episode is titled "It's Not Easy Being a Buzz Band." Frankie Rose, Beach Fossils, Tanlines, Best Coast and other discuss such topics as "Bad Credit/No Credit," "Predjudice and Stereotyping" and "Cyberbullying" (hmm) all set to some hilariously tense/dramatic music right out of a Dateline NBC story.

This may all be a little too Hipster Runoff (a clear influence here, check the captions during the interview segments) for the casual music fan, but to anyone who reads this site or Pitchfork regularly (aka you) will get it and should find it very entertaining. And in this segmented world we live in, there’s no reason this couldn’t actually air on MTV2 at 3:41 AM on Friday nights. Until then it’s online, you can watch the whole thing at the bottom of this post.