Search for ‘David Graeber’ (6 articles found)

The Bitcoin Bubble

… It might seem that Bitcoin is just like a fiat currency issued by governments. Writing in the Wall Street Journal, Jack Hough says precisely that it’s a purely online currency with no intrinsic value; its worth is based solely on the willingness of holders and merchants to accept it in trade. In that respect, it’s not so different from fiat currencies like the dollar or Euro, but whereas governments back such money, Bitcoins lack central control. But this is a misunderstanding of what money does and where it came from. The “fiat” (meaning “let there be”) in “fiat money” reflects the power of governments to command and tax. Because of their power to tax, governments can make money by fiat, simply by declaring their willingness to accept that money in repayment of tax debts.

Historically, money arose from, and in conjunction with, this power. (This point has been made repeatedly over the years, most recently in David Graeber’s controversial Debt: The First 5000 Years, a surprise publishing hit for an anthropologist. )

By contrast, Bitcoin looks more like the “just so” story, commonly told in economics textbooks, in which money arises to simplify what would otherwise be complex and cumbersome barter transactions.

That would be fine if Bitcoin were simply a unit of account, used to keep track of transactions. But all the interest in Bitcoin is in the idea that it is a store of value, one that may be expected to show steady appreciation rather than depreciation. So Bitcoin needs to be evaluated as a financial asset.

Viewed in this way, Bitcoin is perhaps the finest example of a pure bubble. It beats the classic historical example, produced during the 18th century South Sea Bubble of “a company for carrying out an undertaking of great advantage, but nobody to know what it is.” After all, the promoter of this enterprise might, in principle, have had a genuine secret plan. Bitcoin also outmatches Ponzi schemes, which rely on the claim that the issuer is undertaking some kind of financial arbitrage (the original Ponzi scheme was supposed to involve postal orders). The closest parallel is the fictitious dotcom company imagined in Garry Trudeau’s Doonesbury, whose only product was its own stock.

As with any kind of asset used as currency, from gold to tobacco to U.S. dollars, Bitcoin is valuable as long as people are willing to accept it. But in all of these examples, willingness to hold the asset depends on the fact that it has value independent of that willingness. Tobacco can be smoked or chewed, gold can be used to fill teeth or make jewellery, and U.S. dollars can be used to meet obligations to the U.S. government.

This independent value is not fixed and stable. If people give up smoking, or wearing gold jewellery, or if the United States experiences inflation, the external value of these currencies will decline.

But in the case of Bitcoin, there is no source of value whatsoever. The computing power used to mine the Bitcoin is gone once the run has finished and cannot be reused for a more productive purpose. If Bitcoins cease to be accepted in payment for goods and services, their value will be precisely zero.

According to the efficient-markets hypothesis (EMH), which still dominates the analysis of financial markets, this should be impossible. The EMH states that the market value of an asset is equal to the best available estimate of the value of the services or income flows it will generate. In the case of a company stock, this is the discounted value of future earnings. Since Bitcoins do not generate any actual earnings, they must appreciate in value to ensure that people are willing to hold them. But an endless appreciation, with no flow of earnings or liquidation value, is precisely the kind of bubble the EMH says can’t happen […]

Comment by mrajanov, on April 17, 2013 — 5:13am:

This thing called Bitcoins is a non-entity in most practical senses. It is poorly designed and, in any case, even if it were designed soundly it would face serious threats from systemic actors with whom it competes.

Having said that, there are a few inaccuracies and technical errors here—

But in the case of Bitcoin, there is no source of value whatsoever. The computing power used to mine the Bitcoin is gone once the run has finished and cannot be reused for a more productive purpose. If Bitcoins cease to be accepted in payment for goods and services, their value will be precisely zero.

It can be shown that these sentiments are incorrect in that they are expressed in absolute terms. The value of Bitcoins could be zero in the scenario above, but this is not necessarily so. This is because it is a matter of market and social practice rather than economic theory.

For example, even putting aside that gold can be used in fillings, computers, wedding rings… et cetera, it has a conceptually distinct value relating to the special status that the market and society have given it in acting as a store of value, an instument of psychological comfort if you will. There is an implicit guarantee (a poor, but effective, term in this instance) that gold can be sold to someone else at some price in recognition of the uncertanties of a complex economic world and the psychological comfort that is consequently sought. There is no explicit guarantee. Whatsoever. It is simply that society (the “market” in some sense) has given it this role, accepted it, to the point where it will endure for the foreseeable future. It is not efficient — but it is reality. The below sentiments are spot on in that sense (especially in relation to gold once the distractions of tooth fillings and such are removed)—

they represent the sharpest ever refutation of the efficient-markets hypothesis.

If society, the market, were to consider Bitcoins as a better tool for the role (say it’s more compact, transportable, exchangeable, reliable, secure, non-perishable.. whatever attributes may be considered relevant at that time), then it is possible that Bitcoins could take on the role that society has currently bestowed on gold.

Because of Bitcoins’s technical and structural defects this is not likely but it is conceptually possible and therefore the absolutist statements above are inaccurate.

There is no economic reality outside our own thoughts and behaviour. There is no economic system outside the one we create.

At this stage of our evolutionary process, anyway.

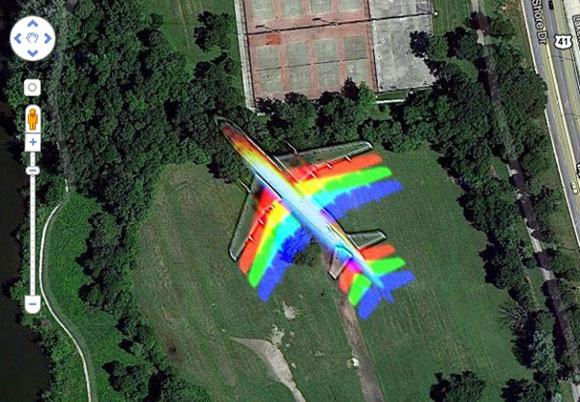

Stories from the New Aesthetic

James Bridle is fond of a satellite photograph of the border between Namibia and South Africa — in the middle of a desert, alongside the Orange River, there are two blocks of shimmering green pixels. They’re actually very tidy rectangular fields, but Bridle holds that, to today’s eyes, its difficult to see this gridded pattern of monochrome shades as anything other than pixels.

This variety of paradox was at the center of “Stories From The New Aesthetic,” the penultimate discussion in a series put on by Rhizome, at the New Museum.

The three speakers — Aaron Straup Cope, of the Cooper-Hewitt; Joanne McNeil, editor of Rhizome; and Bridle, the writer who coined “the New Aesthetic“ (but is quick to point out that he’s not proud of the phrase) — spoke of their increasing awareness of, and developing attitudes about, the integration of technology and everyday life. Specifically, the way they begin to behave when they overlap or reflect each other.

The fact that satellite imagery and fairly precise GPS location is readily available for anyone with a new phone might be commonplace, but the scale of that realization, both in terms of its global ubiquity and the complexity of the necessary support system becomes dumbfounding in even a larger historical frame. Only a few decades ago, the nuclear-powered submarines of the two most heavily invested militaries the world has ever known could not target ballistic missiles acceptably because, on a basic level, the submarines couldn’t even tell exactly where they were.

The now-continuous intersection between the physical world and its computer representations was the starting point for the three highly caffeinated imaginations on display at the New Museum. Cope, previously a geolocation engineer at Flickr, dilated on the echoes of reality and its schematic representation: reflections piling upon each other, and sets of overlapping data becoming increasingly rife with meaning — intended and otherwise. The complexity of possible interpretations led to a comparision of the eery oscillations of elevator statistical recordings and undersea whale calls. In such cases, the mapping of patterns against each other can often go awry. When this happens on the machine side, the feedback loops and glitches generated can seem to offer new worlds to human perception.

Bridle was struck by a list of the most productive editors on Wikipedia — presently the human race’s most exhaustive single reference resource — in which the majority were, in fact, robots. Especially in the most frequently-used networked interfaces, the pattern-matching of machines in bits of software appears to intimately interpenetrate with our own forms of recognition. The slippage between the two can be powerfully disorienting as well: in Bridle’s project Where The Fuck Was I? he unlocked his iPhone’s logged GPS data, which had traced his location in a kind of geographical diary for the previous year. But, as he explained in the discussion, he noticed later that there were places logged that he couldn’t have been — hovering above the Thames, perhaps — that were rather the product of phone’s heuristic means of locating itself:

It’s finding itself according to a whole network that we can’t really perceive. This is an atlas made by robots that is not just about physical space, but is about frequencies in the air and the vagaries of the GPS system. It’s an entirely different way of seeing space.

Joanne McNeil approached the mysteries of robot vision from the opposite direction: she observed that Google Maps’ anonymized faces are animated by their ambiguity, their strangeness heightened by their appearance in frozen, starkly exposed physical spaces. A similar kind of imposed narrative arose from Apple’s recent map update, in which its warped topology gave birth to structures and locations that seem to melt into puddles or crawl in jagged zig-zags across a plane. While these errors can be looked at solely as hazards for navigation, McNeil argued they can also be seen as seams through which the narrative of the human “way of seeing” compares to a machine’s.

There is such a preponderance of the “beauty of glitches” in talk of the New Aesthetic that it’s easy to start to think that’s simply what the phrase refers to. But it seemed to me the range of examples is not so easily circumscribed. Similar projects like Jon Rafman’s 9 Eyes — a collection of wide-angle images snapped in Google Street View — tend to be driven by what Henri Cartier-Bresson called “decisive moments.” On occasion they come from the distorions of space or color that affect the Google camera at critical angles, but mostly they are moments frozen in an instant of heightened significance: a nude standing by the shore, a band of wild horses glimpsed behind ancient gravestones. Their beauty arises almost entirely from the strictly human elements of their contents.

The term might seem to better suit Greg Allen’s reprinting of “Wohlgemeynte Gedanken über den Dannemarks-Gesundbrunnen”, in which a 2008 Google Books scan rendered an 18th-century treatise on “hydrologie” into impressively flowing and rippling typographical landscapes. Released as an eBook, Allen’s piece navigates a turbulent space between printed matter and digital representation, from the accident as an artistic origin and the unknowable logic of a failing optical scanner. But again, its force derives from the reflexivity of its maker, and the object’s pose within established codes of art-making and visual beauty.

The talk surrounding The New Aesthetic urged some further level of comprehension or intermeshing of human and machine modes of understanding. (At times during the talk, I felt alone in my doubt about whether present-day machines can be said to “understand” in any sense that retains the word’s meaning.) If the New Aesthetic is to metabolize the kinds of refraction and layering between codes and languages — or ways of seeing — it seemed to me its examples ought to emerge not from happy coincidence, but rather from the explicit, perhaps eery, echoes between different worlds.

What seemed to go unsaid, or perhaps was implicitly rejected, was the established complaint about the portal of representative technology, first made by philosophers like Jean Baudrillard and Umberto Eco, for whom representation and distancing were forms of impoverishing “the real.” A new form of this disappointment was expressed by the anthropologist David Graeber in a recent essay for The Baffler:

The technologies that have advanced since the seventies are mainly either medical technologies or information technologies — largely, technologies of simulation (…) the only breakthroughs were those that made it easier to create, transfer, and rearrange virtual projections of things that either already existed, or, we came to realize, never would (…) The postmodern moment was a desperate way to take what could otherwise only be felt as a bitter disappointment and to dress it up as something epochal, exciting, and new.

The most profound suggestion behind all the various limbs of the New Aesthetic is that something new can be found not just in linear progress through “the real” (which perhaps might be better put as simply “the material”). It might be found, instead, in the strange undertones in the resonance between the way a representation is automatically generated and the way we have come to think of it in the complacency of our ordinary material existence.

That point of intersection — between representation and reality — is, after all, where art has always found meaning. Bridle stressed that, to truly understand that hall of mirrors as it exists today, we must search these systems for the keys to unlock them from the inside, before they will be comprehensible, first we must “find the right metaphors.” Though Theodor Adorno may well have been dismayed at these prospects, I think one of his instructions remains apt: “Teach the petrified forms how to dance by singing them their own song.”

Flying cars, technology and labor

At the turn of the millennium, I was expecting an outpouring of reflections on why we had gotten the future of technology so wrong. Instead, just about all the authoritative voices—both Left and Right—began their reflections from the assumption that we do live in an unprecedented new technological utopia of one sort or another.

The common way of dealing with the uneasy sense that this might not be so is to brush it aside, to insist all the progress that could have happened has happened and to treat anything more as silly. “Oh, you mean all that Jetsons stuff?” I’m asked—as if to say, but that was just for children! Surely, as grown-ups, we understand The Jetsons offered as accurate a view of the future as The Flintstones offered of the Stone Age.

Even in the seventies and eighties, in fact, sober sources such as National Geographic and the Smithsonian were informing children of imminent space stations and expeditions to Mars. Creators of science fiction movies used to come up with concrete dates, often no more than a generation in the future, in which to place their futuristic fantasies. In 1968, Stanley Kubrick felt that a moviegoing audience would find it perfectly natural to assume that only thirty-three years later, in 2001, we would have commercial moon flights, city-like space stations, and computers with human personalities maintaining astronauts in suspended animation while traveling to Jupiter. Video telephony is just about the only new technology from that particular movie that has appeared—and it was technically possible when the movie was showing. 2001 can be seen as a curio, but what about Star Trek? The Star Trek mythos was set in the sixties, too, but the show kept getting revived, leaving audiences for Star Trek Voyager in, say, 2005, to try to figure out what to make of the fact that according to the logic of the program, the world was supposed to be recovering from fighting off the rule of genetically engineered supermen in the Eugenics Wars of the nineties.

By 1989, when the creators of Back to the Future II were dutifully placing flying cars and anti-gravity hoverboards in the hands of ordinary teenagers in the year 2015, it wasn’t clear if this was meant as a prediction or a joke.

The usual move in science fiction is to remain vague about the dates, so as to render “the future” a zone of pure fantasy, no different than Middle Earth or Narnia, or like Star Wars, “a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away.” As a result, our science fiction future is, most often, not a future at all, but more like an alternative dimension, a dream-time, a technological Elsewhere, existing in days to come in the same sense that elves and dragon-slayers existed in the past—another screen for the displacement of moral dramas and mythic fantasies into the dead ends of consumer pleasure.

Might the cultural sensibility that came to be referred to as postmodernism best be seen as a prolonged meditation on all the technological changes that never happened? The question struck me as I watched one of the recent Star Wars movies. The movie was terrible, but I couldn’t help but feel impressed by the quality of the special effects. Recalling the clumsy special effects typical of fifties sci-fi films, I kept thinking how impressed a fifties audience would have been if they’d known what we could do by now—only to realize, “Actually, no. They wouldn’t be impressed at all, would they? They thought we’d be doing this kind of thing by now. Not just figuring out more sophisticated ways to simulate it.”

That last word—simulate—is key. The technologies that have advanced since the seventies are mainly either medical technologies or information technologies—largely, technologies of simulation. They are technologies of what Jean Baudrillard and Umberto Eco called the “hyper-real,” the ability to make imitations that are more realistic than originals. The postmodern sensibility, the feeling that we had somehow broken into an unprecedented new historical period in which we understood that there is nothing new; that grand historical narratives of progress and liberation were meaningless; that everything now was simulation, ironic repetition, fragmentation, and pastiche—all this makes sense in a technological environment in which the only breakthroughs were those that made it easier to create, transfer, and rearrange virtual projections of things that either already existed, or, we came to realize, never would. Surely, if we were vacationing in geodesic domes on Mars or toting about pocket-size nuclear fusion plants or telekinetic mind-reading devices no one would ever have been talking like this. The postmodern moment was a desperate way to take what could otherwise only be felt as a bitter disappointment and to dress it up as something epochal, exciting, and new.

In the earliest formulations, which largely came out of the Marxist tradition, a lot of this technological background was acknowledged. Fredric Jameson’s “Postmodernism, or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism” proposed the term “postmodernism” to refer to the cultural logic appropriate to a new, technological phase of capitalism, one that had been heralded by Marxist economist Ernest Mandel as early as 1972. Mandel had argued that humanity stood at the verge of a “third technological revolution,” as profound as the Agricultural or Industrial Revolution, in which computers, robots, new energy sources, and new information technologies would replace industrial labor—the “end of work” as it soon came to be called—reducing us all to designers and computer technicians coming up with crazy visions that cybernetic factories would produce.

End of work arguments were popular in the late seventies and early eighties as social thinkers pondered what would happen to the traditional working-class-led popular struggle once the working class no longer existed. (The answer: it would turn into identity politics.) Jameson thought of himself as exploring the forms of consciousness and historical sensibilities likely to emerge from this new age.

What happened, instead, is that the spread of information technologies and new ways of organizing transport—the containerization of shipping, for example—allowed those same industrial jobs to be outsourced to East Asia, Latin America, and other countries where the availability of cheap labor allowed manufacturers to employ much less technologically sophisticated production-line techniques than they would have been obliged to employ at home.

From the perspective of those living in Europe, North America, and Japan, the results did seem to be much as predicted. Smokestack industries did disappear; jobs came to be divided between a lower stratum of service workers and an upper stratum sitting in antiseptic bubbles playing with computers. But below it all lay an uneasy awareness that the postwork civilization was a giant fraud. Our carefully engineered high-tech sneakers were not being produced by intelligent cyborgs or self-replicating molecular nanotechnology; they were being made on the equivalent of old-fashioned Singer sewing machines, by the daughters of Mexican and Indonesian farmers who, as the result of WTO or NAFTA — sponsored trade deals, had been ousted from their ancestral lands. It was a guilty awareness that lay beneath the postmodern sensibility and its celebration of the endless play of images and surfaces.

Why did the projected explosion of technological growth everyone was expecting—the moon bases, the robot factories—fail to happen? There are two possibilities. Either our expectations about the pace of technological change were unrealistic (in which case, we need to know why so many intelligent people believed they were not) or our expectations were not unrealistic (in which case, we need to know what happened to derail so many credible ideas and prospects).

David Graeber on jubilee

David Johnson: At the end of the book, you suggest one policy proposal of a sort, namely a jubilee, or a cancellation of all debts.

David Graeber: Well, it’s not really a policy proposal—I don’t believe in policy. I’m an anarchist, right? Policy means other people making decisions for you.

DJ: Right. Have you thought about how a jubilee would work right now, in terms of all the underwater mortgages in this country or on the sovereign debt crisis in Europe?

DG: I haven’t worked it out; I’m not an economist. But there are people who have. Boston Consulting Group, I believe, ran a model recently and came to the conclusion that, while having a debt jubilee would cause great economic disruption, not having one would create even more. The situation we have basically isn’t viable. Some kind of radical solution is going to be required at some point; the question is what form it’s going to take.

This time around, they might consider doing it in a form that actually helps ordinary people. It would have been perfectly feasible to take the trillions of dollars that they essentially printed to bail out the banks and give it to mortgage holders, because what the banks had were mortgage-based securities that were no good anymore. If they just paid the mortgages using the same money, that in effect would have bailed out the banks.

DJ: That wouldn’t have been a debt cancellation.

DG: Well, I’m just giving an example. It would have had the same effect as a debt cancellation, because they would have printed money to pay the debts. The irony is that they chose instead to give the money directly to the banks and not bail out the mortgage-holders. Which is a pattern that you see over and over again in world history—one of the more dramatic consistencies I’ve noticed in the history of debt: debts between equals are not the same as debts between people who are not equals.

Debts between either poor people or rich people, that they have with each other, can be renegotiated or forgiven. People can be extraordinarily generous, understanding, forgiving when dealing with others like themselves. But debts between social classes, between the rich and the poor, suddenly become a matter of absolute morality. And that’s what we saw; it’s a very, very old pattern.

David Graeber on bureaucratic technologies

Thursday, January 19, 7pm

The twentieth century produced a very clear sense of what the future was to be, but we now seem unable to imagine any sort of redemptive future. Anthropologist and writer David Graeber asks how did this happen? One reason is the replacement of what might be called poetic technologies with bureaucratic ones. Another is the terminal perturbations of capitalism, which is increasingly unable to envision any future at all. Presented by the MFA Art Criticism and Writing Department.

SVA Theatre, 333 West 23 Street

Free and open to the public

David Graeber on the barter myth

The persistence of the barter myth is curious. It originally goes back to Adam Smith. Other elements of Smith’s argument have long since been abandoned by mainstream economists—the labor theory of value being only the most famous example. Why in this one case are there so many desperately trying to concoct imaginary times and places where something like this must have happened, despite the overwhelming evidence that it did not?

It seems to me because it goes back precisely to this notion of rationality that Adam Smith too embraced: that human beings are rational, calculating exchangers seeking material advantage, and that therefore it is possible to construct a scientific field that studies such behavior. The problem is that the real world seems to contradict this assumption at every turn. Thus we find that in actual villages, rather than thinking only about getting the best deal in swapping one material good for another with their neighbors, people are much more interested in who they love, who they hate, who they want to bail out of difficulties, who they want to embarrass and humiliate, etc.—not to mention the need to head off feuds.

Even when strangers met and barter did ensue, people often had a lot more on their minds than getting the largest possible number of arrowheads in exchange for the smallest number of shells. Let me end, then, by giving a couple examples from the book, of actual, documented cases of ‘primitive barter’—one of the occasional, one of the more established fixed-equivalent type.

The first example is from the Amazonian Nambikwara, as described in an early essay by the famous French anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss. This was a simple society without much in the way of division of labor, organized into small bands that traditionally numbered at best a hundred people each. Occasionally if one band spots the cooking fires of another in their vicinity, they will send emissaries to negotiate a meeting for purposes of trade. If the offer is accepted, they will first hide their women and children in the forest, then invite the men of other band to visit camp. Each band has a chief and once everyone has been assembled, each chief gives a formal speech praising the other party and belittling his own; everyone puts aside their weapons to sing and dance together—though the dance is one that mimics military confrontation. Then, individuals from each side approach each other to trade:

If an individual wants an object he extols it by saying how fine it is. If a man values an object and wants much in exchange for it, instead of saying that it is very valuable he says that it is worthless, thus showing his desire to keep it. ‘This axe is no good, it is very old, it is very dull’, he will say… [8]

In the end, each “snatches the object out of the other’s hand”—and if one side does so too early, fights may ensue.

The whole business concludes with a great feast at which the women reappear, but this too can lead to problems, since amidst the music and good cheer, there is ample opportunity for seductions (remember, these are people who normally live in groups that contain only perhaps a dozen members of the opposite sex of around the same age of themselves. The chance to meet others is pretty thrilling.) This sometimes led to jealous quarrels. Occasionally, men would get killed, and to head off this descending into outright warfare, the usual solution was to have the killer adopt the name of the victim, which would also give him the responsibility for caring for his wife and children.

The second example is the Gunwinngu of West Arnhem land in Australia, famous for entertaining neighbors in rituals of ceremonial barter called the dzamalag. Here the threat of actual violence seems much more distant. The region is also united by both a complex marriage system and local specialization, each group producing their own trade product that they barter with the others.

In the 1940s, an anthropologist, Ronald Berndt, described one dzamalag ritual, where one group in possession of imported cloth swapped their wares with another, noted for the manufacture of serrated spears. Here too it begins as strangers, after initial negotiations, are invited to the hosts’ camp, and the men begin singing and dancing, in this case accompanied by a didjeridu. Women from the hosts’ side then come, pick out one of the men, give him a piece of cloth, and then start punching him and pulling off his clothes, finally dragging him off to the surrounding bush to have sex, while he feigns reluctance, whereon the man gives her a small gift of beads or tobacco. Gradually, all the women select partners, their husbands urging them on, whereupon the women from the other side start the process in reverse, re-obtaining many of the beads and tobacco obtained by their own husbands. The entire ceremony culminates as the visitors’ men-folk perform a coordinated dance, pretending to threaten their hosts with the spears, but finally, instead, handing the spears over to the hosts’ womenfolk, declaring: “We do not need to spear you, since we already have!” [9]

In other words, the Gunwinngu manage to take all the most thrilling elements in the Nambikwara encounters—the threat of violence, the opportunity for sexual intrigue—and turn it into an entertaining game (one that, the ethnographer remarks, is considered enormous fun for everyone involved). In such a situation, one would have to assume obtaining the optimal cloth-for-spears ratio is the last thing on most participants’ minds. (And anyway, they seem to operate on traditional fixed equivalences.)

Economists always ask us to ‘imagine’ how things must have worked before the advent of money. What such examples bring home more than anything else is just how limited their imaginations really are. When one is dealing with a world unfamiliar with money and markets, even on those rare occasions when strangers did meet explicitly in order to exchange goods, they are rarely thinking exclusively about the value of the goods. This not only demonstrates that the Homo Oeconomicus which lies at the basis of all the theorems and equations that purports to render economics a science, is not only an almost impossibly boring person—basically, a monomaniacal sociopath who can wander through an orgy thinking only about marginal rates of return—but that what economists are basically doing in telling the myth of barter, is taking a kind of behavior that is only really possible after the invention of money and markets and then projecting it backwards as the purported reason for the invention of money and markets themselves. Logically, this makes about as much sense as saying that the game of chess was invented to allow people to fulfill a pre-existing desire to checkmate their opponent’s king.

* * *

At this point, it’s easier to understand why economists feel so defensive about challenges to the Myth of Barter, and why they keep telling the same old story even though most of them know it isn’t true. If what they are really describing is not how we ‘naturally’ behave but rather how we are taught to behave by the market—well who, nowadays, is doing most of the actual teaching? Primarily, economists. The question of barter cuts to the heart of not only what an economy is—most economists still insist that an economy is essentially a vast barter system, with money a mere tool (a position all the more peculiar now that the majority of economic transactions in the world have come to consist of playing around with money in one form or another) [10]—but also, the very status of economics: is it a science that describes of how humans actually behave, or prescriptive, a way of informing them how they should? (Remember, sciences generate hypothesis about the world that can be tested against the evidence and changed or abandoned if they don’t prove to predict what’s empirically there.)

Or is economics instead a technique of operating within a world that economists themselves have largely created? Or is it, as it appears for so many of the Austrians, a kind of faith, a revealed Truth embodied in the words of great prophets (such as Von Mises) who must, by definition be correct, and whose theories must be defended whatever empirical reality throws at them—even to the extent of generating imaginary unknown periods of history where something like what was originally described ‘must have’ taken place?