Search for ‘Virginia Woolf’ (9 articles found)

'Magisterial but muffled'

In her mid-twenties, [Elizabeth Hardwick] had befriended the singer [Billie Holiday] in New York. In darkling fashion, her [1976 NYRB] essay recalls textures and spectacles of the 1940s: the “underbrush” of cheap hotel interiors, fingertips split while rummaging through secondhand-record racks, the birdlike figures of great jazz musicians as they stooped out of taxis and into the clubs. And at the center of it all, the “puzzling phantom” of Holiday herself, who is heard to speak only once in the whole piece. Her character leaches out instead in performance, in relations with her tired and flummoxed entourage, in vignettes of addiction, illness, imprisonment. Most of all in the odd, skewed language Hardwick has fashioned to evoke her, with its vexing repetitions and sly inversions: “She was fat the first time we saw her, large, brilliantly beautiful, fat.”

How exactly to describe Hardwick’s singular style? For sure, it is a kind of lyricism, a method that allows her as a critic to bring the reader close to her subject via the seductions first of sound and second of image and metaphor. (In the Times Literary Supplement in 1983, the British novelist David Lodge called Hardwick the first properly lyric critic since Virginia Woolf, but this cannot be true: the lyric mode is indispensable even to a criticism that imagines it’s doing something quite else.) Joan Didion has approved Hardwick’s “exquisite diffidence,” and in an interview for the Paris Review, she herself remarked: “The poet’s prose is one of my passions. I like the offhand flashes, the absence of the lumber in the usual prose.” There is a sense always that Hardwick’s sentences stand alone, pay little or no attention to one another, that each is a self-involved and sufficient whole. She advances (if that’s the word) paratactically: impression piled upon impression, analogy stacked against analogy, till she runs out of conceits and gives it to us relatively strict and straight.

The metaphors in Hardwick’s essays are always unusual, which is what one wants from a metaphor. They are often simply bizarre, or strained as far as they will go. She can be straightforwardly graceful and apposite, as in the opening sentence of “Bloomsbury and Virginia Woolf”: “Bloomsbury is, just now, like one of those ponds on a private estate from which all of the trout have been scooped out for the season.” But what are we to make of the moment when, having told us that Zelda Fitzgerald’s biography had been buried, she goes further and says that Zelda lies beneath the “desperate violets” of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s memories? Hardwick, who had abandoned a dissertation on metaphysical poetry to become a writer, was ever committed to the vivid, cumbrous oddity that could be canvassed in metaphor.

Thomas Keymer on Autobiography

Thomas De Quincey invited comparison with Rousseau in Confessions of an English Opium-Eater, but relinquished Rousseau’s sense of personal control. The opium becomes a rival protagonist of his story, almost at times a rival author. It strips away the ‘veil between our present consciousness and the secret inscriptions on the mind’ and opens the narrative, in proto-psychoanalytic ways, to dream and unreason. De Quincey sees how strange it is to use an inherited literary model to express one’s own uniqueness, and at one point wonders if he might not in fact be ‘counterfeiting my own self’… Influential accounts of the genre like Laura Marcus’s Auto/biographical Discourses (1994) have emphasised the way identity seemed to fracture in literary modernism. Katherine Mansfield’s scepticism about ‘our persistent yet mysterious belief in a self which is continuous and permanent’; Louis MacNeice’s wry sense that ‘as far as I can make out, I not only have many different selves, but I am often, as they say, not myself at all.’ In Virginia Woolf’s remarkable ‘A Sketch of the Past’, drafted as she wrote her biography of Roger Fry, the gap between narrating and narrated selves – ‘the two people, I now, I then’ – proves recalcitrant and persistent, refusing to close. In any case, the self Woolf sought to document was not so much subject as object: not a self-determining agent but ‘the person to whom things happen’, acted on by immense, inscrutable social forces. To consider these forces, their power and their invisibility, is to realise ‘how futile life-writing becomes’, Woolf writes: ‘I see myself as a fish in a stream; deflected; held in place; but cannot describe the stream.’

Hitch thanks you for smoking (1992)

- Tobacco: A History by V.G. Kiernan

Radius, 249 pp, £18.99, December 1991, ISBN 0 09 174216 1 - The Faber Book of Drink, Drinkers and Drinking edited by Simon Rae

Faber, 554 pp, £15.99, November 1991, ISBN 0 571 16229 0

Hard by the market in Cambridge is or was Bacon’s the tobacconist, and on Bacon’s wall, if it stands yet, there’s an engraved poem by Thomas Calverley of which I can still quote a stave or two when maundering over the port and nuts (before the brandy stage):

Thou who when cares attack, bidst them avaunt and black

Care from the horseman’s back, vaulting unseatest.

Sweet when blah blah in clay, sweet when they’ve cleared away

Lunch and at close of day,

Possibly sweetest.

Calverley goes on to heap scorn on those who impugn the habit, ridiculing the notion that it is torpor-inducing and fraught with disease. This was the first ‘Thank you for Smoking’ sign that I – playing truant from a Methodist public school up the road – ever saw, and I appreciated it. Round a corner or two in Petty Cury was King Street, where there stood a rank of pubs. A rite of passage in those days was to inhale a pint of suds in each within the space of an hour – the ‘King Street run’ – without puking, or without puking until the end. A novel and film of the period captures a proletarian version of this easy-to-grasp wheeze:

The bartender placed a pint before him. He paid one-and-eightpence and drank it almost in a single gulp. His strength magically returned, and he shouted for another, thinking: the thirteenth. Unlucky for some, but we’ll see how it turns out. He received the pint and drank a little more slowly, but half-way through it the temptation to be sick became a necessity that beat insistently against the back of his throat. He fought it off and struggled to light a cigarette.

Smoke caught in his windpipe and he had just time enough to push his way back through the crush ... before he gave way to the temptation that had stood by him since falling down the stairs, and emitted a belching roar over a middle-aged man sitting with a woman on one of the green leather seats.

Alan Sillitoe. Saturday Night and Sunday Morning

‘Belching roar’ is, I think, bloody good (you notice that Sillitoe is writing so plastered that it reads as if it’s the poor old temptation that fell down the stairs), and I like the symbiosis of booze and nicotine that he brings off so cleanly. Anyway, at Bacon’s one purchased the first illicit Perfecto – brand names mattered to the neophyte and in King Street the first stoups of flat-as-ink Greene King (‘drink your beer before it gets cold’), and it was an induction no less potent than the heated gropings in the Arts Cinema that was ready to hand.

How did one get from that to this? From smoking after dinner to smoking between courses – the inter-course cigarette – to smoking between bites? From drinking to acquire a manly hangover to drinking to dissolve an inhuman one? From having a cigarette after the act to reaching blindly for one during it? From explaining, Lucky Jim-like, to a hostess that you have burned and soused her sheets to explaining that you have singed her shower-curtain? How did all that happen? Eh? The jammed, thieving fag-machine that I nearly kicked to death long after all the pubs had closed and the last train had gone and the glass looked wide enough to reach through. The hotel mini-bar that I unsmilingly up-ended into my suitcase, dwarf Camparis compris, when about to take a plane to Libya. The pawing through the garbage – through the fridge, actually – in search of the lost cigarette packet. The broad-minded, sneering assault on the cooking sherry when the interviewee says: ‘No, in fact we don’t keep it in the house but perhaps there’s a glass of ...’ Here are the milestones of shame, or a few of them.

Both of these books oscillate between praise and admonition, and come dangerously close at times to suggesting that drinking and smoking are all right in moderation. Victor Kiernan would be incapable of saying anything so trite. But his book is the record of a long farewell to a much-loved addiction, and he has not permitted his change of heart to make him into a fanatical opponent. The population is praised for puffing its way stoically through the shrieking pieties of King James I, whose pamphlet on the matter warned loyal subjects that it was ‘a custom loathsome to the eye, hateful to the nose, harmful to the brain, dangerous to the lungs’. The tendency of those in authority to show who’s in charge by issuing no-smoking edicts is detestable to Kiernan, who recoils instinctively from the martinet, the headmaster, the dominie and the bureaucrat. Weaving together an immense collection of quotations (though no Calverley, alas), he has one very heartening story which may be true even though it has Lord Dacre for its authority. After the suicide of the anti-smoking fanatic Adolf Hitler, it seems, all the bunker deputies began to light up: ‘now the headmaster had gone and the boys could break the rules. Under the soothing influence of nicotine’, they could look facts in the face.

Engels is also prayed in aid, as having written that one of the worst privations of the workhouse system was that ‘tobacco is forbidden.’ And Marx reflected gloomily, as many a freelance scribbler has done whose stipend won’t cover his humble snout bill, that ‘Capital will not even pay for the cigars I smoked writing it.’ The political economy of tobacco, on which Kiernan touches, is rather iffy from the radical point of view. Colonial Virginia and Southern Rhodesia rested on forms of peonage if not slavery, and Cuba is probably more disfigured than otherwise by its reliance on a tobacco economy. (Indeed, it would be interesting to study the degeneration of the Cuban revolution as a function of a semi-colonial system that produced only things – sugar, rum and cigars – that are supposed to be bad for you.) Pierre Salinger – or Pierre Schlesinger as I always want to call him – once told me that he was telephoned by President Kennedy and asked to calculate how many Cuban cigars there were in all of Washington. He replied that he didn’t know, but could discover how many cigar stores there were. ‘Well, go to all of them, Pierre, and buy every Havana they’ve got.’ The mystified underling completed his task, and only learned its meaning later that night, when Kennedy announced an embargo on Cuban cigars for everybody else.

Smoking is, in men, a tremendous enhancement of bearing and address and, in women, a consistent set-off to beauty. Who has not observed the sheer loveliness with which the adored one exhales? That man has never truly palpitated. It is the essential languor of the habit which lends it such an excellent tone in this respect, as Oscar Wilde understood so well when he described it as an occupation. Kiernan thrills to his own description of Greta Garbo blowing out a match in The Flesh and the Devil, and vibrates as he recalls Paul Henreid taking a smoke from his own lips and passing it to Bette Davis (Now, Voyager). With approval, he cites the mass meeting of young women at Teheran University; every pouting lip framing a cigarette in protest at a Khomeini fatwah against smoking for females.

In spite of the misogyny of certain styles of smoking (pipes, of course, and Rudyard Kipling’s hearty attitude towards cigars – ‘a woman is only a woman, but a good cigar is a smoke’) and Thackeray (‘both knew that the soothing plant of Cuba is sweeter to the philosopher than the prattle of all the women in the world’), there is also a definite intimacy in the lighting ritual and in the mutual bowing over the flame. Nor, though it can catch you in the wind a bit, does smoking impair relations with the opposite sex in the way drinking has been known to do. (‘No honey, we don’t have a few drinks. We get drunk!’ – Days of Wine and Roses; or: ‘My god, my leg! I can’t feel it! I can’t move it!’ ‘It’s my leg, you bloody fool.’ I speak from experience.)

Kiernan’s sweetest note is struck when he contemplates the wondrous effect of tobacco on the creative juices. Having reviewed the emancipating influence of a good smoke on the writing capacities of Virginia Woolf, Christopher Isherwood, George Orwell and Compton Mackenzie, he poses the large question whether ‘with abstainers multiplying, we may soon have to ask whether literature is going to become impossible – or has already begun to be impossible.’ It’s increasingly obvious, as one reviews new books fallen dead-born from the modem, that the meretricious blink of the word-processor has replaced, for many ‘writers’, the steady glow of the cigarette-end and the honest reflection of the cut-glass decanter. You used to be able to tell, with some authors, when the stimulant had kicked in. Kingsley Amis could gauge the intake of Paul Scott page by page – a stroke of magnificent intuition which is confirmed by the Spurting biography, incidentally; and the same holds with writers like Koestler and Orwell, depending on whether or not they had a proper supply of shag.

Kiernan suggests that both Marx and Tolstoy may have suffered irretrievable damage as writers from having sworn off smoking in late middle age; he has no difficulty in showing that Pavese also experienced great challenges to his concentration from trying to give up, and that poor old Charles Lamb (who took up smoking while trying to give up drinking) was stuck miserably, like the poor cat in the adage, between temptation and abstinence, to the detriment of his powers.

If I was to update Calverley I would include a stanza or two on the splendour of cigarettes as levellers and ice-breakers while travelling. Auden may have coupled ‘the shared cigarette’ with ‘the fumbled unsatisfactory embrace before hurting’, but if you are stuck with a language barrier and a high cultural hurdle there is no gesture more instantly requited than the extended packet and the shared match. This partly explains the popularity of the gasper among journalists, explorers and reporters. Now that most newsrooms ban the blue haze (and, in the case of the anal-sadist Murdoch, the agreeable fumes of booze as well), the atmosphere of most newspaper bureaux is like that of some sodding law firm. And, in the written outcome, it sodding well shows.

Searching unnecessarily for a socially-conscious peroration with which to close his literate, broad-minded and considered guide to the history of a grand subject, Kiernan turns faintly censorious at the last. He says sternly that ‘it is the poorer classes and countries that go on smoking,’ and mentions tobacco in the same breath and sentence as Aldous Huxley’s ‘Soma’. This allows him some boilerplate about the danger of drugs being ‘utilised by dictators to manage public opinion’, and a cry that ‘mankind should throw physic of this kind to the dogs, and cure itself instead by radical reform of the worm-eaten social fabric, the moral slum we all inhabit today.’ Och aye, or yeah, yeah if you prefer. One of the sterling qualities of tobacco leaf is its support for privacy and introspection; its reliability in solitary confinement and the dugout; its integrity. A long, slow expression of fragrant smoke into the face of the ranter and the bully has been the sound, demotic response since the days of King James the bad, and should be our continued prop and stay in these fraught and ‘judgmental’ times.

The hard stuff, of course, is a different matter. Uncollected in the Faber anthology is a moment in Michael Wharton’s ‘Peter Simple’ memoir when one of the more heroic Fleet Street pub-performers kept a long-postponed appointment with his doctor. After tapping and humming away, the quack inquired mildly; ‘D’you drink at all?’ Well-primed for the routine, and knowing that doctors tend to double mentally the intake that you specify, our hero merely said that he did take a dram here and there. ‘Well,’ said the physician, ‘if I were you I’d cut out that second sherry before dinner.’ So intoxicated was the patient by this counsel that he went straight back to the boozer, bought sextuples all round on the strength of the story, and had to go home in about five taxis.

When the effects of drink are not extremely funny, they do have a tendency to be a bit grim. For every cheerful fallabout drunk there is a lugubrious toper or melancholy soak, draining the flask for no better reason than to become more repetitive or dogmatic. But there’s a deep, attractive connection between the Italian for flask – fiasco – and the nerve of humour. When Peter Lawford or Dean Martin observed that it must be wretched being a non-drinker, because when you woke in the morning that was the best you were going to feel all day, they brushed that nerve. So did the porter in Macbeth. There are, of course, some who stand there pissed and weeping and give the porter an argument, to the effect that the male ego is actually rendered stouter and sturdier by drink, or at least by a hangover. Those who have found this are going to need K. Amis’s terse but limpid chapter on the distinction between metaphysical and physical hangover. Bear in mind, first, as he says, that ‘if you do not feel bloody awful after a hefty night then you are still drunk, and must sober up in a waking state before the hangover dawns.’ Two keen reinforcements of this insight are included in the anthology. One is Adrian Henri’s ‘He got more and more drunk as the afternoon wore off.’ The other is James Fenton on, if not in, ‘The Skip’:

And then ... you know how if you’ve had a few

You’ll wake at dawn, all healthy, like sea breezes,

Raring to go, and thinking; ‘Clever you!

You’ve got away with it.’ And then, oh Jesus ...

These are the men who have been out and done the hard thinking for all of us. At all events, K. Amis compresses all the dos and don’ts of hung-over venery in a skilled manner which makes one bawl like a pub bore: ‘Cheers mate! You said it!’ (Those interested in cross-referencing the subjects of this review will need to note what he says about the nicotine ingredient in the modern hangover – something that was beyond the reach even of Jeeves’s celebrated pick-me-ups.)

Smokers are in no real position to engage in denial, though I suppose there can be closet smoking, while drinkers can persuade themselves of practically anything between, as it were, cup and lip. It is amazing to read Byron’s bemused speculations (‘was it the cockles, or what I took to correct them?’) about his insurgent interior, when ‘what he took to correct them’, after a heavy dinner of shellfish and wine, was ‘three or four glasses of spirits, which men (the vendors) call brandy, rum or Hollands’. Of course, it could have been the cockles, couldn’t it? And then there are always old saws, like my father’s sapient favourite ‘Don’t mix the grape and the grain.’ I never understood this until it was too late, by which time it translated absurdly as keeping Scotch and wine in separate compartments of the inner bloke. Stuff and nonsense! Still, you do get people whining on about this, like Sebastian’s friend in Brideshead after he (Sebastian, not the temptation, you fool) had vomited copiously through Charles Ryder’s window:

His explanations were repetitive and, towards the end, tearful. ‘The wines were too various,’ he said, ‘it was neither the quality nor the quantity that was at fault.’ It was the mixture. Grasp that and you have the root of the matter. To understand all is to forgive all.

Arguably. The best variant of this excuse comes from Billy Connolly, in his impersonation of a lurching Glaswegian gaping down at what is known in that city as ‘a pavement bolognese’. At length he concludes: ‘It’s no’ the Guinness that does it. It’s those diced carrots.’

I once saw the following manoeuvre actually performed, on the morrow of a Tory Party Conference in Blackpool, though the article employed was a necktie:

O’Neill would prop himself against the bar and order his shot. The bartender knew him, and would place the glass in front of him, toss a towel across the bar, as though absentmindedly forgetting it, and move away. Arranging the towel around his neck, O’Neill would grasp the glass of whiskey and an end of the towel in one hand and clutch the other end of the towel with his other hand. Using the towel as a pulley, he would laboriously hoist the glass to his lips.

Arthur and Barbara Gelb. O’Neill

There’s a very good ‘Rock Bottom’ section in this collection, designed for those who know what it’s like to spill more than most people drink. Charles Jackson’s maxim from The Lost Weekend, ‘Never put off till tomorrow what you can drink today,’ might serve as a representative extract for much longer and more elaborate babblings, such as the full text of John Berryman’s ‘Step One’, prelude to the general confession he made for Alcoholics Anonymous, wherein the sufferer relates all the harm he has done himself and others. If the day ever comes when I pin that document above my typewriter, it will be because the funny side just isn’t enough. Extracts, for the flavour:

Passes at women drunk, often successful ... Lost when blacked-out the most important professional letter I have ever received ... Made homosexual advances drunk, 4 or 5 times ... Gave a public lecture drunk ... Defecated uncontrollably in a university corridor, got home unnoticed ...

Unnoticed by whom? Of course, as this proves, and as the meeting of the United Grand Junction Ebenezer Temperance Association in the Pickwick Papers also illustrates, it’s a sign of alcoholism to make rules about how much you drink.

There’s a fatal attraction at work here (or don’t you find that?) and it’s to be found as much in the literature of dossing as in the pathetic fallacy which, as Waugh says, resounds in our praise of fine wine. Listen to the beauty of Peter Reading, (who also found the beauty of Perduta Gente), in his poem ‘Fuel’:

Melted-down boot polish, eau de Cologne, meths,

surgical spirit,

kerosene, car diesel, derv ...

This touches on a problem which, to a more refined plane, is understood even by merely social drinkers such as myself – namely, Where’s the next one coming from? In one of its few klutzy decisions, this volume reprints the whole of Auden’s ‘1 September 1939’, presumably for no better reason than that its set in a bar, and omits his poem ‘On the Circuit’, where he confronts a problem that’s increasingly urgent in today’s America, especially for those of us who fly and drone for a living:

Then the worst of all, the anxious thought,

Each time my plane begins to sink

And the No Smoking sign comes on:

What will there be to drink?

Is this a milieu when I must

How grahamgreeneish! How infra dig!

Snatch from the bottle in my bag

An analeptic swig?

Or, and updating only slightly from 1963, dash off to the gents for a smoke? Experiences like this and reflections like these teach one that only a fool expects smoking and drinking to bring happiness, just as only a dolt expects money to do so. Like money, booze and fags are happiness, and people cannot be expected to pursue happiness in moderation. This distillation of ancient wisdom requires constant reassertion as the bores and prohibitionists and workhouse masters close in.

An encounter with J-P Sartre (2000)

It was early in January 1979, and I was at home in New York preparing for one of my classes. The doorbell announced the delivery of a telegram and as I tore it open I noticed with interest that it was from Paris. ‘You are invited by Les Temps modernes to attend a seminar on peace in the Middle East in Paris on 13 and 14 March this year. Please respond. Simone de Beauvoir and Jean Paul Sartre.’ At first I thought the cable was a joke of some sort. It might just as well have been an invitation from Cosima and Richard Wagner to come to Bayreuth, or from T.S. Eliot and Virginia Woolf to spend an afternoon at the offices of the Dial. It took me about two days to ascertain from various friends in New York and Paris that it was indeed genuine, and far less time than that to despatch my unconditional acceptance (this after learning that les modalités, the French euphemism for travel expenses, were to be borne by Les Temps modernes, the monthly journal established by Sartre after the war). A few weeks later I was off to Paris.

Les Temps modernes had played an extraordinary role in French, and later European and even Third World, intellectual life. Sartre had gathered around him a remarkable set of minds – not all of them in agreement with him – that included Beauvoir of course, his great opposite Raymond Aron, the eminent philosopher and Ecole Normale classmate Maurice Merleau-Ponty (who left the journal a few years later), and Michel Leiris, ethnographer, Africanist and bullfight theoretician. There wasn’t a major issue that Sartre and his circle didn’t take on, including the 1967 Arab-Israeli war, which resulted in a monumentally large edition of Les Temps modernes – in turn the subject of a brilliant essay by I.F. Stone. That alone gave my Paris trip a precedent of note.

When I arrived, I found a short, mysterious letter from Sartre and Beauvoir waiting for me at the hotel I had booked in the Latin Quarter. ‘For security reasons,’ the message ran, ‘the meetings will be held at the home of Michel Foucault.’ I was duly provided with an address, and at ten the next morning I arrived at Foucault’s apartment to find a number of people – but not Sartre – already milling around. No one was ever to explain the mysterious ‘security reasons’ that had forced a change in venue, though as a result a conspiratorial air hung over our proceedings. Beauvoir was already there in her famous turban, lecturing anyone who would listen about her forthcoming trip to Teheran with Kate Millett, where they were planning to demonstrate against the chador; the whole idea struck me as patronising and silly, and although I was eager to hear what Beauvoir had to say, I also realised that she was quite vain and quite beyond arguing with at that moment. Besides, she left an hour or so later (just before Sartre’s arrival) and was never seen again.

Foucault very quickly made it clear to me that he had nothing to contribute to the seminar and would be leaving directly for his daily bout of research at the Bibliothèque Nationale. I was pleased to see my book Beginnings on his bookshelves, which were brimming with a neatly arranged mass of materials, including papers and journals. Although we chatted together amiably it wasn’t until much later (in fact almost a decade after his death in 1984) that I got some idea why he had been so unwilling to say anything to me about Middle Eastern politics. In their biographies, both Didier Eribon and James Miller reveal that in 1967 he had been teaching in Tunisia and had left the country in some haste, shortly after the June War. Foucault had said at the time that the reason he left had been his horror at the ‘anti-semitic’ anti-Israel riots of the time, common in every Arab city after the great Arab defeat. A Tunisian colleague of his in the University of Tunis philosophy department told me a different story in the early 1990s: Foucault, she said, had been deported because of his homosexual activities with young students. I still have no idea which version is correct. At the time of the Paris seminar, he told me he had just returned from a sojourn in Iran as a special envoy of Corriere della sera. ‘Very exciting, very strange, crazy,’ I recall him saying about those early days of the Islamic Revolution. I think (perhaps mistakenly) I heard him say that in Teheran he had disguised himself in a wig, although a short while after his articles appeared, he rapidly distanced himself from all things Iranian.

When in a good and merry mood Trisy would seize a dozen eggs, and a bucket of flour, coerce a cow to milk itself, and then mixing the ingredients toss them 20 times high up over the skyline, and catch them as they fell in dozens and dozens and dozens of pancakes. But her porridge was a very different affair … It dolloped out of a black pan in lumps of mortar. It stank: it stuck.

The making of Marilyn Monroe

As I measured the length and eloquence of Jacqueline Rose’s essay on Marilyn Monroe, I began to hope for that rarity, a detached, scholarly insight into Monroe (LRB, 26 April). I should have noted the first words of special pleading, from Monroe herself: ‘Like any creative human being, I would like a bit more control.’ Why do you have to be ‘creative’ to deserve more control? And isn’t it fanciful to claim that Monroe was the one star who got the better of the moguls? Her partnership with Milton Greene was prompted by Greene’s wish to protect her business ineptness (and promote himself). It led to two films: Bus Stop (her best work it seems to me, though not mentioned by Rose) and The Prince and the Showgirl, which is a mess. Nothing else came of Marilyn Monroe Productions. She failed the key test for stars of the 1950s: taking charge of their own careers. Rose may wonder why Elizabeth Taylor got ten times Monroe’s fee for a film. Was it that Taylor followed better advice? Or that she had a box office record (A Place in the Sun, Giant, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof) and an Oscar (BUtterfield 8)? That prize was charitable, but the generosity reflected the industry’s regard for Taylor. She was smart, hardworking, expert, on time and word-perfect since childhood. Richard Burton’s diaries tell how much he learned from her. Who reckons that Monroe could have attempted Martha in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

Bette Davis and Olivia de Havilland had challenged and defeated the contract system. Katharine Hepburn contrived her own material as early as The Philadelphia Story. Ingrid Bergman made her bold journey to Italy to make ‘real’ films. Grace Kelly, Audrey Hepburn, Doris Day and Susan Hayward rode the studio attitudes of the 1950s without breaking down. Kim Novak was shy and limited as an actress, and vulnerable to male estimates that she was merely sexy. But she did The Man with the Golden Arm, Strangers When We Meet and Picnic – not great pictures, but worthwhile. And she was Madeleine and Judy in Vertigo. Does anyone believe Monroe could have done that film, or lived up to Hitchcock’s need to trap anguished actors in his taut frames?

Yet if Monroe could not generate her own projects, then surely it was up to her to seek the best opportunities available? That fits Judy Holliday, who sometimes reminds one of Monroe as the ‘dumb blonde’, Billie Dawn, in Born Yesterday. Holliday was not dumb, though she was neurotic, but in Adam’s Rib and Born Yesterday she found a democratic intelligence within the dumb blonde archetype that surpasses anything ‘Lincolnian’ in Monroe’s career.

There is an even more telling example of what could be done. When Arthur Miller’s play After the Fall had its debut in 1964, directed by Elia Kazan, the role of Maggie (plainly based on Marilyn) was taken by Barbara Loden. Kazan had had an affair with Monroe before her marriage to Joe DiMaggio, and in A Life he spoke fondly of her. But this inspired discoverer of performers did not make a film with or for Monroe, just as Lee Strasberg’s admiration for Marilyn’s reading of Anna Christie never led to a stage production. Had they realised that Monroe’s spasmodic glow (so magnificent in stills) was hardly viable in a complete dramatic context?

On the other hand, Loden wrote, directed and acted in a poignant, independent movie, Wanda, where she plays a fragile unsmart woman involved with a minor criminal. Wanda is a pioneering achievement, showing that an unfulfilled actress could do something for herself. Much the same applies to Gena Rowlands in A Woman under the Influence and her other work with John Cassavetes. Wanda cost only $200,000 but Loden needed six years to raise the money. She took control and responsibility. Monroe left an estate of just over $90,000, which ended up with the family of Lee Strasberg. Control in Hollywood is more frequent, and more complicated, than Rose allows.

David Thomson

San Francisco

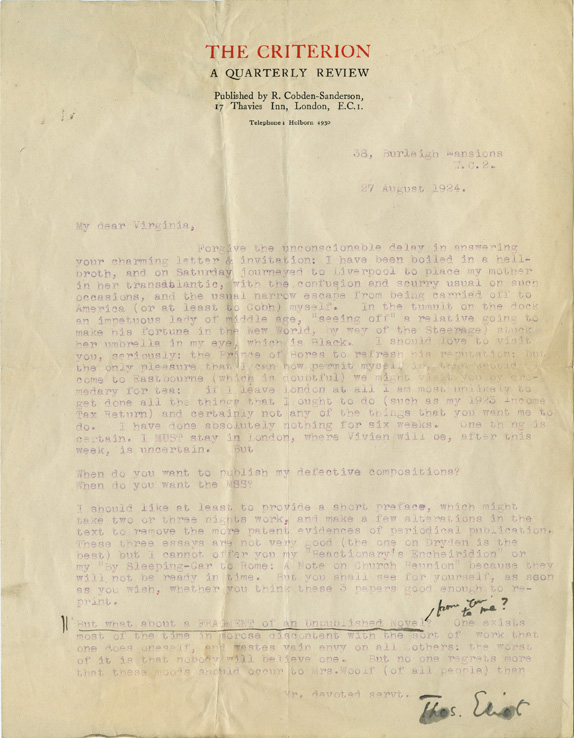

Document: T. S. Eliot to Virginia Woolf

Printed with the permission of the T. S. Eliot Estate.

38 Burleigh Mansions, St Martins Lane, London W.C.2.

27 August 1924

My dear Virginia,

Forgive the unconscionable delay in answering your charming letter and invitation. I have been boiled in a hell-broth, and on Saturday journeyed to Liverpool to place my mother in her transatlantic, with the confusion and scurry usual on such occasions, and the usual narrow escape from being carried off to America (or at least to Cobh) myself. In the tumult on the dock an impetuous lady of middle age, ‘seeing off’ a relative going to make his fortune in the New World, by way of the Steerage) stuck her umbrella in my eye, which is Black. I should love to visit you, seriously: the Prince of Bores to refresh his reputation: but the only pleasure that I can now permit myself is, that should I come to Eastbourne (which is doubtful) we might visit you by dromedary for tea: if I leave London at all I am most unlikely to get done all the things that I ought to do (such as my 1923 Income Tax Return) and certainly not any of the things that you want me to do. I have done absolutely nothing for six weeks. One thing is certain: I MUST stay in London, where Vivien will be, after this week, is uncertain. But

When do you want to publish my defective compositions?

When do you want the MSS?

I should like at least to provide a short preface, which might take two or three nights’ work, and make a few alterations in the text to remove the more patent evidences of periodical publication. These three essays are not very good (the one on Dryden is the best) but I cannot offer you my ‘Reactionary’s Encheiridion’ or my ‘By Sleeping-Car to Rome: A Note on Church Reunion’ because they will not be ready in time. But you shall see for yourself, as soon as you wish, whether you think these three papers good enough to reprint.

But what about a FRAGMENT of an Unpublished Novel from you to me? One exists most of the time in morose discontent with the sort of work that one does oneself, and wastes vain envy on all others: the worst of it is that nobody will believe one. But no one regrets more that these moods should occur to Mrs. Woolf (of all people) than

Yr. devoted servt.

Thos. Eliot

Le Monde's 100 Books of the Century

- The Stranger (The Outsider), Albert Camus (1942)

- Remembrance of Things Past, Marcel Proust (1913-1927)

- The Trial, Franz Kafka (1925)

- The Little Prince, Antoine de Saint-Exupery (1943)

- Man’s Fate, Andre Malraux (1933)

- Journey to the End of the Night, Louis-Ferdinand Celine (1932)

- The Grapes of Wrath, John Steinbeck (1939)

- For Whom the Bell Tolls, Ernest Hemingway (1940)

- Le Grand Meaulnes, Alain-Fournier (1913)

- Froth on the Daydream, Boris Vian (1947)

- The Second Sex, Simone de Beauvoir (1949)

- Waiting for Godot, Samuel Beckett (1952)

- Being and Nothingness, Jean-Paul Sartre (1943)

- The Name of the Rose, Umberto Eco (1980)

- The Gulag Archipelago, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (1973)

- Paroles, Jacques Prevert (1946)

- Alcools, Guillaume Apollinaire (1913)

- The Blue Lotus, Herge (1936)

- The Diary of a Young Girl, Anne Frank (1947)

- Tristes Tropiques, Claude Levi-Strauss (1955)

- Brave New World, Aldous Huxley (1932)

- Nineteen Eighty-Four, George Orwell (1949)

- Asterix the Gaul, Rene Goscinny and Albert Uderzo (1959)

- The Bald Soprano, Eugene Ionesco (1952)

- Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality, Sigmund Freud (1905)

- The Abyss, Marguerite Yourcenar (1968)

- Lolita, Vladimir Nabokov (1955)

- Ulysses, James Joyce (1922)

- The Tartar Steppe, Dino Buzzati (1940)

- The Counterfeiters, Andre Gide (1925)

- The Horseman on the Roof, Jean Giono (1951)

- Belle du Seigneur, Albert Cohen (1968)

- One Hundred Years of Solitude, Gabriel Garcia Marquez (1967)

- The Sound and the Fury, William Faulkner (1929)

- Therese Desqueyroux, Francois Mauriac (1927)

- Zazie in the Metro, Raymond Queneau (1959)

- Confusion of Feelings, Stefan Zweig (1927)

- Gone with the Wind, Margaret Mitchell (1936)

- Lady Chatterley’s Lover, D. H. Lawrence (1928)

- The Magic Mountain, Thomas Mann (1924)

- Bonjour Tristesse, Francoise Sagan (1954)

- Le Silence de la mer, Vercors (1942)

- Life: A User’s Manual, Georges Perec (1978)

- The Hound of the Baskervilles, Arthur Conan Doyle (1901-1902)

- Under the Sun of Satan, Georges Bernanos (1926)

- The Great Gatsby, F. Scott Fitzgerald (1925)

- The Joke, Milan Kundera (1967)

- A Ghost at Noon (Contempt), Alberto Moravia (1954)

- The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, Agatha Christie (1926)

- Nadja, Andre Breton (1928)

- Aurelien, Louis Aragon (1944)

- The Satin Slipper, Paul Claudel (1929)

- Six Characters in Search of an Author, Luigi Pirandello (1921)

- The Resistible Rise of Arturo Ui, Bertolt Brecht (1959)

- Vendredi ou les Limbes du Pacifique, Michel Tournier (1967)

- The War of the Worlds, H. G. Wells (1898)

- If This Is a Man, Primo Levi (1947)

- The Lord of the Rings, J. R. R. Tolkien (1954-1955)

- Les Vrilles de la vigne, Colette (1908)

- Capitale de la douleur, Paul Eluard (1926)

- Martin Eden, Jack London (1909)

- Ballad of the Salt Sea, Hugo Pratt (1967)

- Writing Degree Zero, Roland Barthes (1953)

- The Lost Honour of Katharina Blum, Heinrich Boell (1974)

- The Opposing Shore, Julien Gracq (1951)

- The Order of Things, Michel Foucault (1966)

- On the Road, Jack Kerouac (1957)

- The Wonderful Adventures of Nils, Selma Lagerloef (1906-1907)

- A Room of One’s Own, Virginia Woolf (1929)

- The Martian Chronicles, Ray Bradbury (1950)

- The Ravishing of Lol Stein, Marguerite Duras (1964)

- The Interrogation, J. M. G. Le Clezio (1963)

- Tropisms, Nathalie Sarraute (1939)

- Journal, 1887-1910, Jules Renard (1925)

- Lord Jim, Joseph Conrad (1900)

- Ecrits, Jacques Lacan (1966)

- The Theatre and its Double, Antonin Artaud (1938)

- Manhattan Transfer, John Dos Passos (1925)

- Ficciones, Jorge Luis Borges (1944)

- Moravagine, Blaise Cendrars (1926)

- The General of the Dead Army, Ismail Kadare (1963)

- Sophie’s Choice, William Styron (1979)

- Gypsy Ballads, Federico Garcia Lorca (1928)

- The Strange Case of Peter the Lett, Georges Simenon (1931)

- Our Lady of the Flowers, Jean Genet (1944)

- The Man Without Qualities, Robert Musil (1930-1932)

- Fureur et mystere, Rene Char (1948)

- The Catcher in the Rye, J. D. Salinger (1951)

- No Orchids For Miss Blandish, James Hadley Chase (1939)

- Blake and Mortimer, Edgar P. Jacobs (1950)

- The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge, Rainer Maria Rilke (1910)

- Second Thoughts, Michel Butor (1957)

- The Burden of Our Time, Hannah Arendt (1951)

- The Master and Margarita, Mikhail Bulgakov (1967)

- The Rosy Crucifixion, Henry Miller (1949-1960)

- The Big Sleep, Raymond Chandler (1939)

- Amers, Saint-John Perse (1957)

- Gaston (Gomer Goof), Andre Franquin (1957)

- Under the Volcano, Malcolm Lowry (1947)

- Midnight’s Children, Salman Rushdie (1981)

In the Heart of the Heart of a Color (1976)

In its reliance here on metaphor, language shows us how separate its function must always be from that of sensation. The philosopher’s point Mr. Gass wishes to make in literary terms is that style is not just an addition to language but its essential nature: it enables us to inhabit “the blue” in a literal sense by removing us into the perspective of the sky, away from the earth. Rilke remarked that sex “requires a progressive shortening of the senses.” “I can hear you for blocks,” quips Mr. Gass. “I can smell you, maybe, for a few feet, but I can only touch you on contact. A flashlight held against the skin might as well be off. Art, like light, needs distance, and anyone who attempts to render sexual experience directly must face the fact that the writhings which comprise it are ludicrous without their subjective content…that there is no major art that works close in.” As Yeats put it, and Mr. Gass might well agree, “the tragedy of sexual intercourse is the perpetual virginity of the soul”; but it is the glory and the justification of “blue” language to remain perpetually virgin.

Undeniable; and yet blue can also be for danger, though Mr. Gass would not admit it. Blue boys can want the external world for one thing only—the words they can have it off with. Mr. Gass’s blue style is ideally pornographic because in it “there’s one body only…the body of your work itself.” The country of the blue, while it suggests so well that enchanted space where matter exists in words, is also self-insulating and self-gratifying. That is the risk run by Virginia Woolf as well as by modern stylists and disciples of the blue—Updike, Stanley Elkin (from whose novel, “A Bad Man,” Mr. Gass supplies a savorous quotation) and Mr. Gass himself. The truer stylist— Hardy, James Joyce—has too wide a repertory to play only on what Wallace Stevens called “the blue guitar.” “Ulysses” is made not out of blue but out of Bloom—a man and his meaning. Great writing has in it all colors: Mr. Gass’s favorites manage only one, though he gives himself and us a nice ride over the rainbow.